So I’ve written a lot about the physics of invisibility on this blog and have even written a popular science book on the subject, but many people may not know that I also still occasionally do some research on invisibility physics! I recently had a paper come out on invisibility in the Journal of the Optical Society of America A, and it was even made an “Editor’s Pick” for reading! I thought I would do a short blog post explaining what it’s about. The paper, titled “Objects invisible from multiple directions,” was written by my now former student Dr. Ray Abney and myself; it constituted the final bit of research for Ray’s PhD.

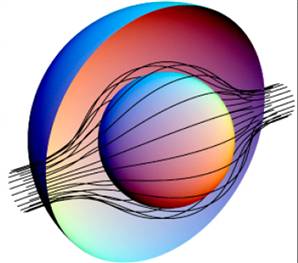

To begin, a little background: though there is a long history of invisibility concepts popping up in physics, it was only in 2006 that research in the area exploded with the simultaneous publication of two theoretical papers arguing that it is in principle possible to construct “invisibility cloaks,” objects that will guide light around a center hidden region and send it along its way as if it had encountered nothing at all. I talked about these original papers a looong time ago on this blog; here, let me just show you an illustration from the paper by Pendry, Schurig and Smith that demonstrates the principle.

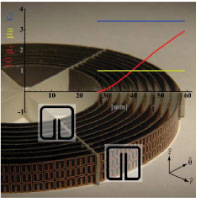

The lines represent light “rays” traveling around that central region. Remarkably, the first prototype of a cloak demonstrating the basic principle was introduced by Schurig et al. that same year; a photograph of their prototype is shown below.

Their device was designed to work at microwave frequencies, where the wavelength of the waves is about 3 cm. The cloak is constructed from a bunch of small elements known as split ring resonators that, when packed together, can act as an optical material with properties not found in nature. Such materials are now known as metamaterials, “beyond” ordinary materials. We note that this device is flat, and was designed to cloak against microwaves propagating through the region between two parallel metal plates. It was a far cry from the ideal theoretical cloak, but demonstrated that the cloaking principles are sound.

The problem with the original 2006 cloaks is that their “perfection” requires material properties that are extremely difficult to produce in a laboratory, especially for visible light wavelengths, which are less than a micron. In particular, the cloaks require anisotropic materials, i.e. materials whose optical response depends on the polarization of light and the direction the light is traveling, as well as magnetic materials that possess a response to the magnetic field of the illuminating light as well as the electric field. Materials that satisfy the conditions to create a “perfect” cloak do not exist in nature and nobody is really sure how to make them in practice, at least at a size that would be useful.

To get around this, researchers have designed modified invisibility devices that trade perfection for simplicity. The microwave cloak mentioned above used simplified material parameters in its design; the result was a cloak that guided waves around the central region but still scattered and reflected some of the waves incident upon it. The implicit reasoning seems to be: making a device that is 90% invisible with current technology is much more efficient than trying to develop new and uncertain technology to get to 100%. (After all, as I have said in talks, the predator from the movie Predator was overall quite visible, but managed to wipe out Arnold Schwarzenegger’s entire special forces unit!)

My own PhD research was on pre-2006 invisibility physics, and so I have a lot of knowledge of the history of the subject. Before 2006, theoreticians had shown that perfect invisibility is impossible for ordinary materials, i.e. materials that are isotropic and non-magnetic. But in 1978, Anthony Devaney published a theoretical paper1 showing that it is possible to make objects that are invisible for any finite number of directions of illumination from ordinary materials — and he presented a mathematical method to design such objects.

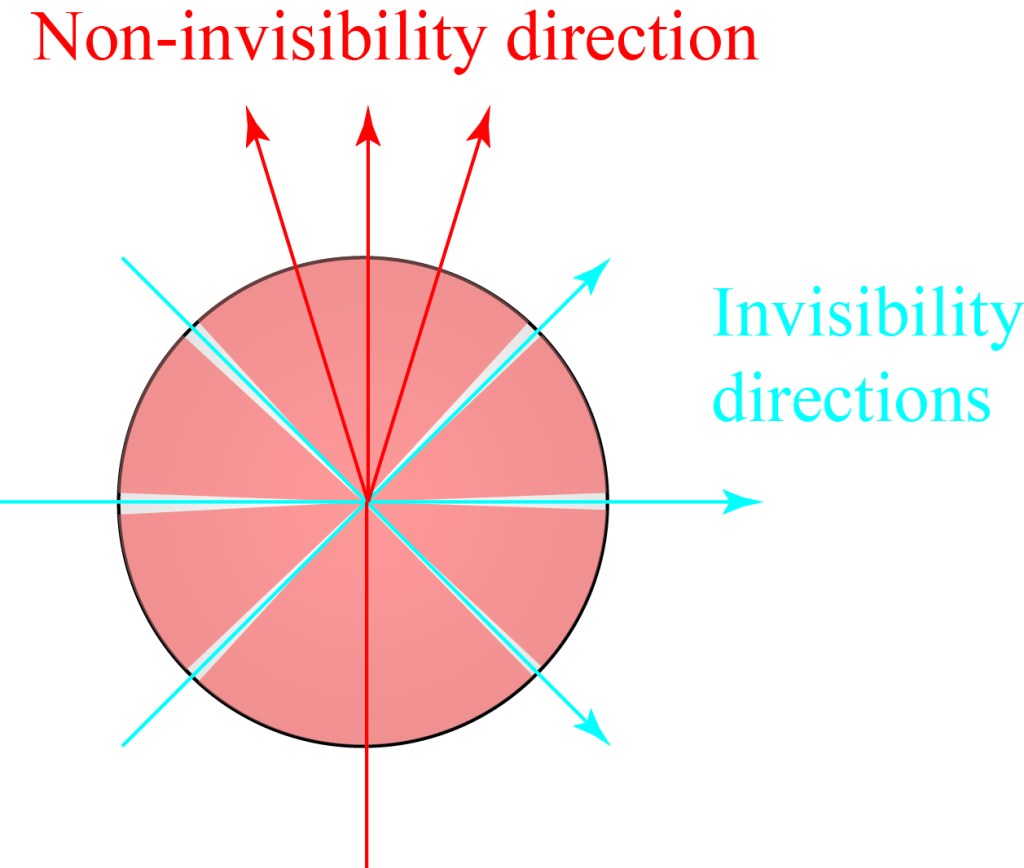

The basic principle is illustrated — crudely — below, for an imagined object that is designed to be invisible from three specific directions. If we illuminate from any of those three directions, the light passes through the object and carries on as if it had encountered nothing. If we illuminate from any other direction — passing through the red regions — the light will be scattered and the object detectable.

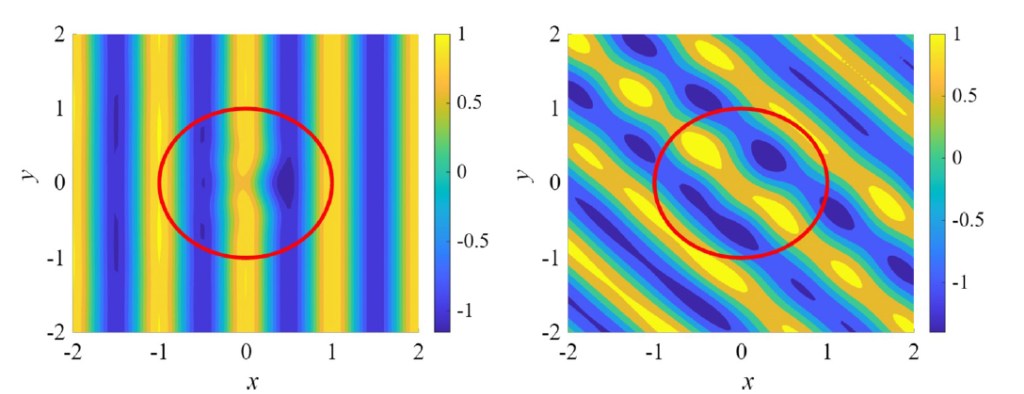

A simulation of light hitting from an invisibility direction and a non-invisibility direction, taken from our paper, is shown below. In the left image, a wave is illuminating the object from the left, and one can see that it passes through the object (outlined with a red circle) with no distortion. The field is distorted within the object, but when it leaves it is as if it never encountered it in the first place. In the right image, a wave comes in at an angle from a non-invisibility direction, and it is significantly distorted all around the object.

A natural question comes up from Devaney’s work, however: what happens if we construct objects that are invisible for an increasing number of directions? In principle, we can construct an object that is invisible for any number of directions, so we could construct an object invisible from 1000 directions, or a million. There seem to be two possible outcomes: 1. As we increase the number of invisibility directions, the object overall becomes increasingly invisible. 2. As we increase the number of invisibility directions, the light scattering between those directions (the red regions in my illustration from before) increases dramatically, keeping the object largely visible.

Ray performed simulations looking at how much the overall scattering of one of Devaney’s objects changes as the number of invisibility directions increases. It should be noted that each of these objects is different, so their overall optical properties were normalized to make sure the same amount of optical “stuff” is present for each object. We constructed two sets of objects using Devaney’s method and looked at the trend as the number of directions increases from N = 1 to N = 6. The objects, like the experimental microwave cloak described earlier, were taken to be two-dimensional to simplify the calculations.

We found that the objects in fact do become overall more invisible as the number of directions is increased! We only needed to consider a small number of invisibility directions because the drop in total scattered power is quite dramatic, dropping orders of magnitude by N = 6. Evidently, even though objects of this sort can never be “perfectly” invisible, they can become arbitrarily close to perfect.

This is a fascinating observation, but doesn’t solve all of our invisibility problems. The material properties of the object are still quite complicated, and Devaney’s method naturally introduces optical gain into the objects, a phenomenon that is hard to implement and control experimentally. It was fascinating to see these properties emerge, as Devaney himself never actually constructed any examples of his objects, he just showed that in principle they could be constructed!

Our research shows that there are still interesting aspects of invisibility to explore, and more approaches available beyond the famous “cloaking” approach of 2006!

******************************************************8

- A. J. Devaney; Nonuniqueness in the inverse scattering problem. J. Math. Phys. 1 July 1978; 19 (7): 1526–1531.

very thoughtful😊