(Alternate title: The old physicist and the sea)

One of the wonderful things about being active in science communication is that you get to meet very interesting people who are involved in a variety of fascinating research activities. If you get very lucky, you might even get a wonderful opportunity to participate in some of those activities!

One great opportunity recently presented itself, thanks to David Shiffman aka “WhySharksMatter” on Twitter who blogs at Southern Fried Science. David does research on shark biology, ecology and conservation, and also works on the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources coastal shark survey. The latter role involves going out on the water in the coastal areas around Charleston, SC to catch and survey the sharks that hang out there. They’ve been taking volunteers out on their day-long trips to help out with the work, and last week I got a chance to go out and survey some sharks!

I thought I’d share some pictures and thoughts on the experience, with the caveat that I’m not a marine biologist and might screw up some details. My wife came along and we turned the trip into an extended weekend in Charleston; in another post, I may share some of the pictures from our other adventures!

The method of the survey is straightforward: go out to a selection of designated coastal areas around Charleston to catch, tag, measure, and release a variety of sharks, noting their species, gender, fork length (length from nose to fork in tail) and total length. The goal of the survey is also straightforward: to monitor the populations of South Carolina sharks. The work is part of a larger survey being done along the Atlantic coast as part of a project called COASTSPAN.

We started very early in the morning on Friday, June 24, at 6:30 am. I was staying at a hotel about a half-hour away from the SCDNR complex, so I ended up having to get up around 5:30. For someone like me, who doesn’t like to get up before 8 am if I can avoid it, this was a challenge! Though I’ve never gotten seasick before, I preemptively took Dramamine, just in case — I didn’t want to be a burden during the day’s measurements. From the SCDNR complex, we took the boat out to the target area, about an hour’s drive away. Four of us participated in the expedition: Jonathan, the senior researcher on the boat, David, myself, and Elizabeth, another volunteer. I was the only one without boat/biology experience!

The boat itself was relatively small and bereft of amenities, not that amenities were particularly needed. We used a small 20 ft McKee Craft, with no shade, no bathroom, and a cooler for snacks and drinks.

I was most worried about the lack of shade — South Carolina gets damn hot in June! Luckily, the sky ended up being overcast for most of the trip and there was a steady breeze. Of the 12 bottles of water and Gatorade I brought for the day, I ended up drinking only 3.

I was most worried about the lack of shade — South Carolina gets damn hot in June! Luckily, the sky ended up being overcast for most of the trip and there was a steady breeze. Of the 12 bottles of water and Gatorade I brought for the day, I ended up drinking only 3.

The first step in the expedition, of course, was putting the boat in the water. As the only one without boating experience, I got to sit on the sidelines while Jonathan drove the boat, David drove the truck, and Elizabeth unhooked.

From there, we took a quick high-speed boat ride to the survey area, which I would describe as coastal marshland. In the next picture, we see a bird investigating a pile of oystershells; I believe the bird is, in fact, an American oystercatcher.

To catch the sharks, two different techniques were employed at two different sites. The first used was the “long line“, in which an approximately 250 ft long line is lined with baited hooks at regular intervals. In the picture below, David prepares the line for deployment, while the collection of 50 hooks can be seen stretched across a square board to his right.

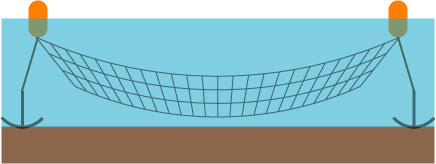

I believe this line ended up resting at the bottom of the body of water. It was marked by a pair of buoys at either end, and weighted down by anchors, as I’ve tried to show in the following illustration.

Every thirty minutes, the line is picked up at one end and the boat is moved along its length. Any sharks caught are tagged and measured, while any hooks missing bait are replaced.

We caught our first sharks on this line; in the picture below, Jonathan is holding one of the very first, which I believe is a finetooth shark or a sharpnose shark.

Were you expecting something bigger? You shouldn’t have, considering we were in a very small boat and boating around shark nursery areas! You can see the already attached numbered tag on the dorsal fin of the shark. This tag allows us to identify and track sharks that are recaptured; on this trip, we in fact recaptured two sharks from a previous trip (and, eventually, we recaptured a shark that we had caught earlier in the day).

Below is a picture of one of the sharks still on the hook, waiting to be measured and tagged. I’m not exactly sure what type this is; during the trip we caught sandbar sharks, finetooth sharks, sharpnose sharks, blacktip sharks, and one bonnethead shark. With the exception of the bonnethead, the sharks all looked very similar to a novice like me.

I actually have relatively few pictures of myself holding sharks! Though I handled plenty of them during the trip, I was really focused on doing a good job in my role as volunteer and less on getting good photos. One of my pictures with a shark is below.

The little fellow looks like a toy! On seeing the photo, Kevin Zelnio of Deep Sea News commented, “What!? You call THAT a shark?? What has David got you doing, playing with shark dolls??”

Even the little ones are remarkably powerful, though: the damn things are all muscle! I had to be warned at one point to avoid grabbing the sharks by the tail, because they can easily twist around and deliver a nasty bite!

In my second shark portrait, you can see David and Elizabeth pulling in and rebaiting the long line. This shark is a little bigger!

The second technique used for catching sharks was gillnetting. A “gillnet” is almost self-explanatory: a net that has holes not quite big enough for fish to swim through, and which gets stuck on the fish when they try to swim back out, trapping them. Like the long line, the gillnet was secured by a pair of anchors at either end, with buoys to mark their positions, as illustrated below.

The net was checked every thirty minutes, just like the long line. The net was brought in by lifting it over the bow of the boat, and dragging the boat along the length of the net, removing sharks and other creatures along the way. The sharks can get really tangled in the net, and it is rather nerve-wracking to try and untangle a really pissed-off, toothy shark! (I, for the most part, let the others do it.) I otherwise helped out drawing the net in, and managed to get myself quite filthy in the process.

We caught more than sharks on our expedition. The crab pictured below turned up in the gillnet and wandered the deck for a while before we tossed him back in. Note the weird protuberances in its shell, which are apparently self-attached as part of its disguise strategy.

The crabs can actually be quite a nuisance; they will happily steal bait off of the long line while it rests on the bottom!

Another rather ticked off guest was the stingray that Jonathan is holding in the picture below.

Its barbed tail, not pictured, was whipping around like the tail of the alien queen in “Aliens” when we brought it on board! Fortunately Jonathan was able to remove the hook from its mouth and send it on its way without incident.

All in all, we caught 39 sharks during our time out on the water! We would have caught more, except that we ran out of bait prematurely. It is normal for the researchers to catch additional bait, namely small fish, while out on the boat; in the picture below, Jonathan tries his hand at catching a few.

We were horribly unlucky, however, and only caught two little fish! After a quick lunch on the boat, and one more attempt to catch some bait, we drew in the fishing gear. Below is a picture of David and Elisabeth drawing in the gillnet.

All packed up, we headed back to shore. Along the way, we caught sight of a really big dorsal fin:

There was nothing to worry about, though — it was just a friendly dolphin! A number of them were shadowing the boat on the way back to the launch, as were quite a few seagulls — we were tossing unused bait over the side, and the birds were going nuts over it.

Once the boat was back on the trailer, we headed back to Charleston. On the way, we stopped for a snack at an unusual store called the Sewee Output, where I posed for a picture with David.

Sewee is quite the… interesting place, selling products such as the following turkey lure:

Overall, the shark tagging trip was a wonderful, fun, and educational experience! I’d like to thank David and the SCDNR for the opportunity to participate in such a fascinating project.

I believe the SCDNR volunteer program will continue for the foreseeable future, but David will no longer be a part of it! He is moving to Florida to earn his Ph.D at the University of Miami, looking at why sharks matter to ocean ecology. I wish him the best of luck with his research, and hope to spend a day on a future shark tagging project as a volunteer with his new group!