2024 marks the 65th anniversary of a significant milestone in optics: the publication of Principles of Optics by Max Born and Emil Wolf, a comprehensive book on physical optics that has been cited some 78,000 times in the scientific literature according to Google Scholar. The book went through seven editions before the passing of both coauthors, with the seventh expanded edition released by Cambridge University Press in 1999. It is a scientific book influential enough to have its own Wikipedia page.

The first edition of Principles of Optics, released in 1959, was a completely expanded and revised edition of Max Born’s own optics book, Optik, that had only appeared in German. Born was close to retirement age, and he enlisted the aid of a bright young PhD of Czech descent, Emil Wolf, to help him with the work. Wolf at that time was very interested in the field of optical coherence, i.e. how the statistical properties of light influence its observable properties, and he pushed to include a chapter on coherence in the book. This turned out to be a very fortuitous decision, as the first laser was invented in 1960, and coherence theory was crucial for understanding the properties of this strange new source of light. This helped catapult Principles of Optics into being perhaps the book on the fundamentals of optical physics for the next 60-plus years.

To commemorate this anniversary, Optics & Photonics News released a retrospective article on the writing of the book and its revision in 1999 (subscription required, alas). The author Patricia Daukantas, reached out to me for some of my thoughts on the 1999 edition, as I was a student of Emil Wolf at that time. I also provided a few high-resolution photos of Emil and his students that I had in my possession. Only one of them was used in the final article, so I thought I would share them here and a few words about each.

I started working with Emil around 1996, thanks to a fateful lunch at Taco Bell with my classmate Scott Carney who was already working with him. I was feeling that experimental high energy particle physics wasn’t a good fit for me, and Scott noted that Emil was looking for more students. I ended up meeting with Emil, who was already 74 years old, and the first thing that he did was acknowledge his age in a rather humorous way. From memory, this is what I recall him saying:

You should consider that I’m old and could die at any time, but my doctors

say I’m in good health and I’m still doing a lot of work.

He then dumped a pile of scientific papers on my lap — reprints and preprints — and told me to read through them and see what I found interesting. I noted that the extremely thick pile of papers he had given me were all from the last five years, and that convinced me that he wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Emil had many, many students over his long career, and he kept in close touch with most of them. Honestly, he and his wife Marlies treated his students like family. Very early in my work with him, in 1996, I experienced that personally, as I was invited to a gathering at the Wolf house where a bunch of his current and former students had gathered for a party.

The very next year, 1997, was Emil’s 75th birthday. A special session of the Optical Society of America’s annual meeting in Long Beach was organized to present talks and celebrate Emil’s life and career; my classmate Scott had the great idea to make t-shirts that said “Year of the Wolf” on them to wear.

There was, of course, a party after the special session, and it was a really impressive “who’s who” of researchers in optical coherence theory and physical optics in general.

Emil’s wife Marlies would often attend the Optical Society meetings with him, and we were all delighted to have her company. I am really happy that I have a nice photo of the two of them together at the Long Beach gathering.

Next up is another casual photo of students and colleagues at the Emil Wolf celebration.

One more photo from that gathering: the group photo.

In 1998, we had another new student in the Wolf group: Sergey Ponomarenko. The next photo was the entirety of the Wolf group in that year.

It’s somewhat funny that every student from about 1990 onwards thought that they would certainly be Emil’s last student, from Scott to me to Sergey and onwards, and most of us were wrong! Emil would continue working into the early 2010s. The photo above was taken, I believe, when we were returning from a working lunch, but it wasn’t just a random occasion: Emil’s former student Girish Agarwal was in town for a visit.

Visits from former students and other collaborators were common in those days, and I made a lot of great contacts during my time with Emil.

While I was in Rochester, Emil finally regained the rights to Principles of Optics, and was able to work on the 7th edition with Cambridge, which included significant new material on diffraction theory, scattering theory, and even computed tomography. It finally included a description of Rayleigh-Sommerfeld diffraction theory, and I am proud to have made a suggestion to Emil on how to present it that made it into the book.

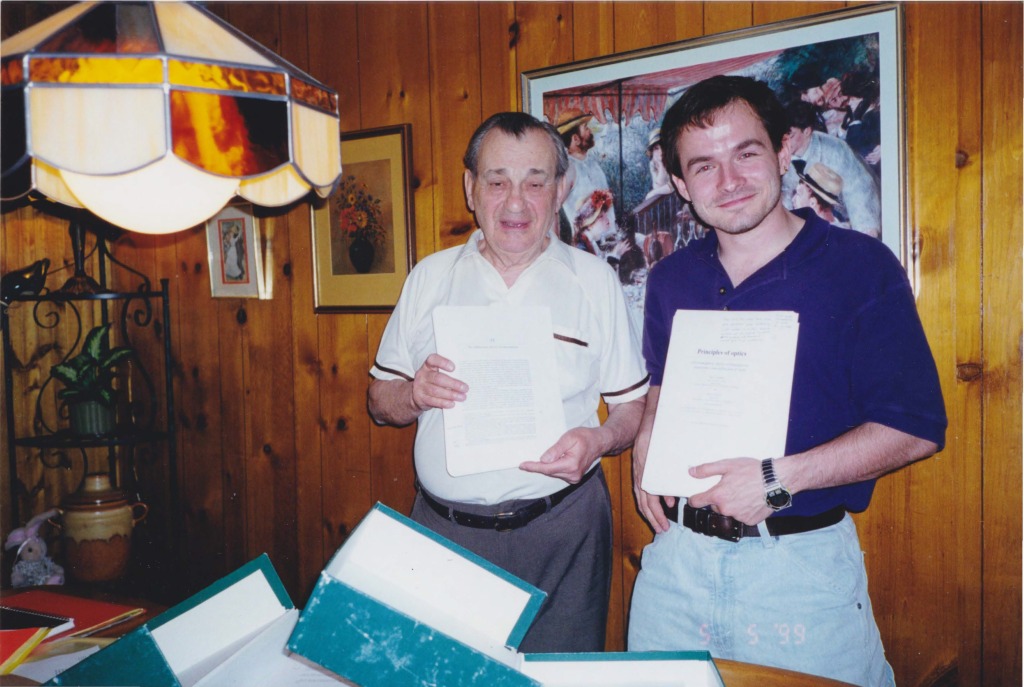

I have joked for years since then that I am one of the few people who has read Principles of Optics cover to cover, as I ended up reading the proofs of the 7th edition in their entirety to look for mistakes that might have been entered when the book was completely typeset. (Whether I understood or retained any of that information is another story.) Another big challenge was revising the index of the book for the new edition; Emil was proud at how comprehensive and thorough the original index was, and there was no method for us to revise it at the time other than to go through the index entry-by-entry and find the new page number in the proofs. I volunteered to help Emil work on this, simply because I enjoyed hanging out with him and Marlies at their home. When we finally finished the index revisions, I suggested we take a few photos to commemorate the completion of the book, even though both of us were exhausted.

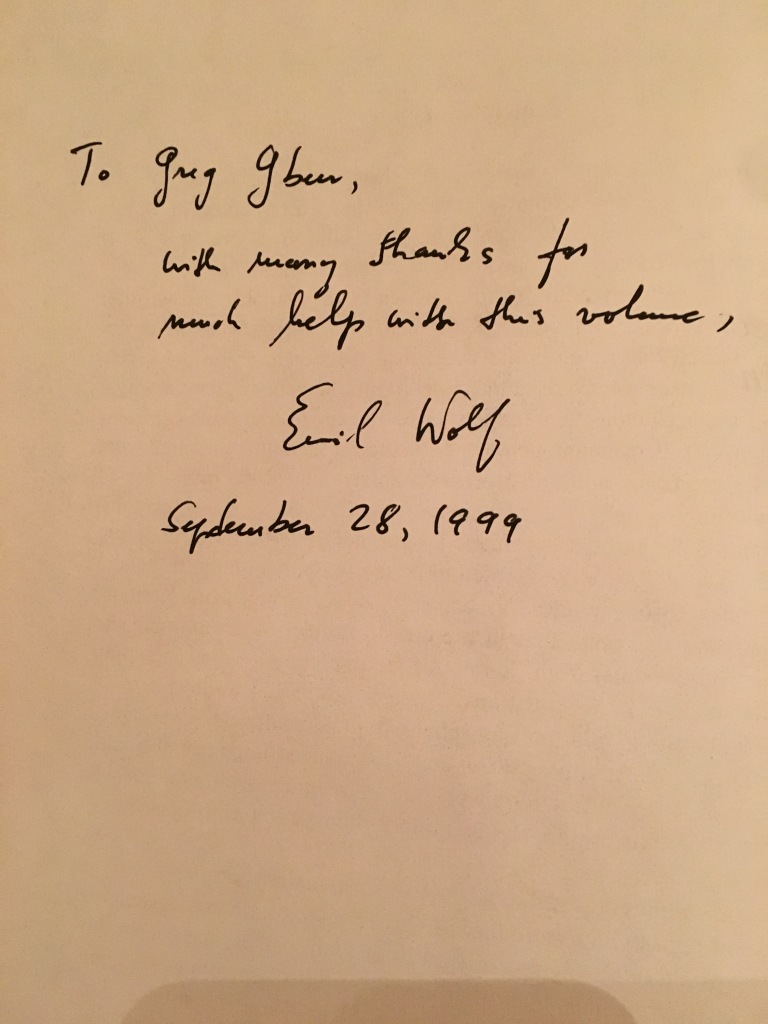

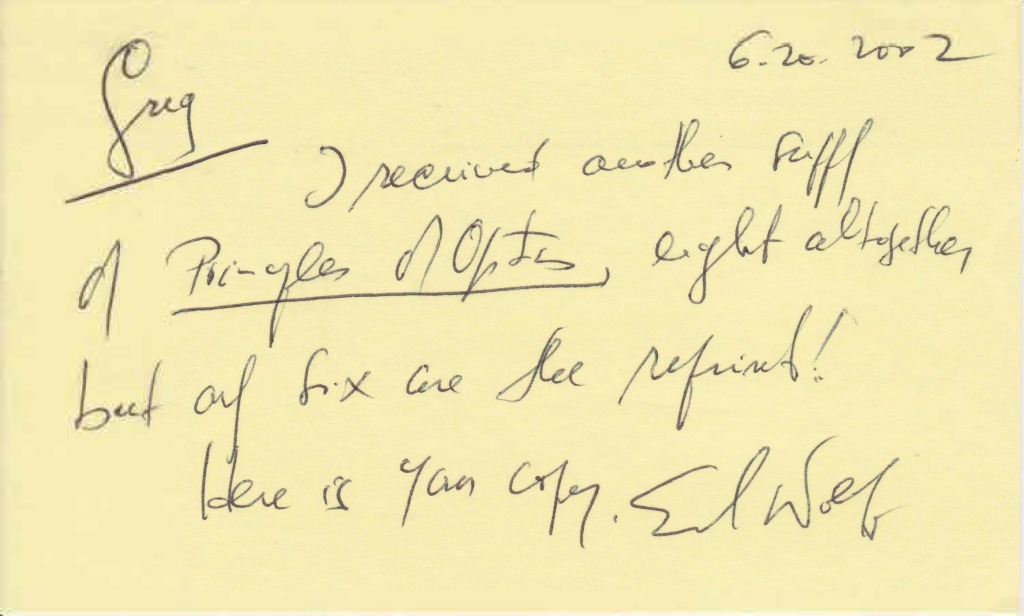

When the first copies of the book came out, I got a copy autographed with thanks from Emil for all the work I did to help him.

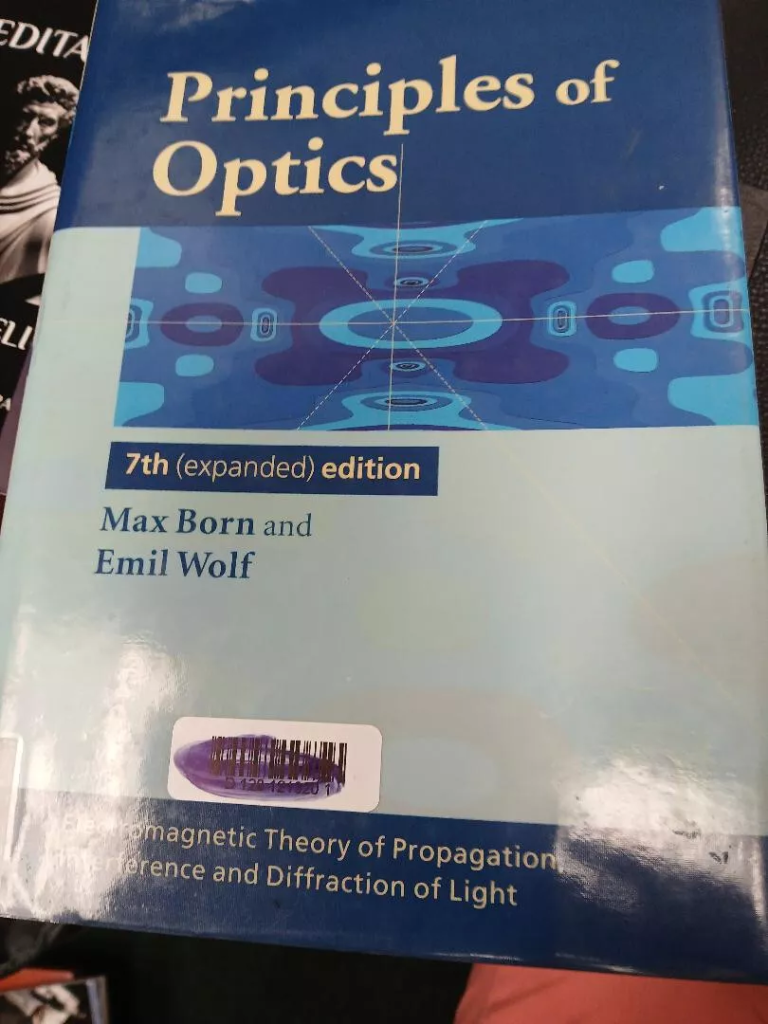

There was one curious wrinkle with the cover of the 7th edition: the very first printing contained a mistake! I found this photo online of this printing.

The image on the cover is the intensity pattern of light focused by a lens near the geometric focus, and inspired by the work that Emil had done on the subject with Linfoot back in 1956. Scott Carney volunteered to do a revised version by computer for the cover, and much to Emil’s chagrin had it completed within an hour: Emil did the original version by hand over the course of months!

Inexplicably, however, when Cambridge formatted the image for the cover, the lines indicating the region of geometric focus were shifted off-center, something else that irritated detail-oriented Emil immensely. Cambridge vowed to fix the problem for the next printing, which came out in 2002. Emil presented me with a new copy of the book at that time.

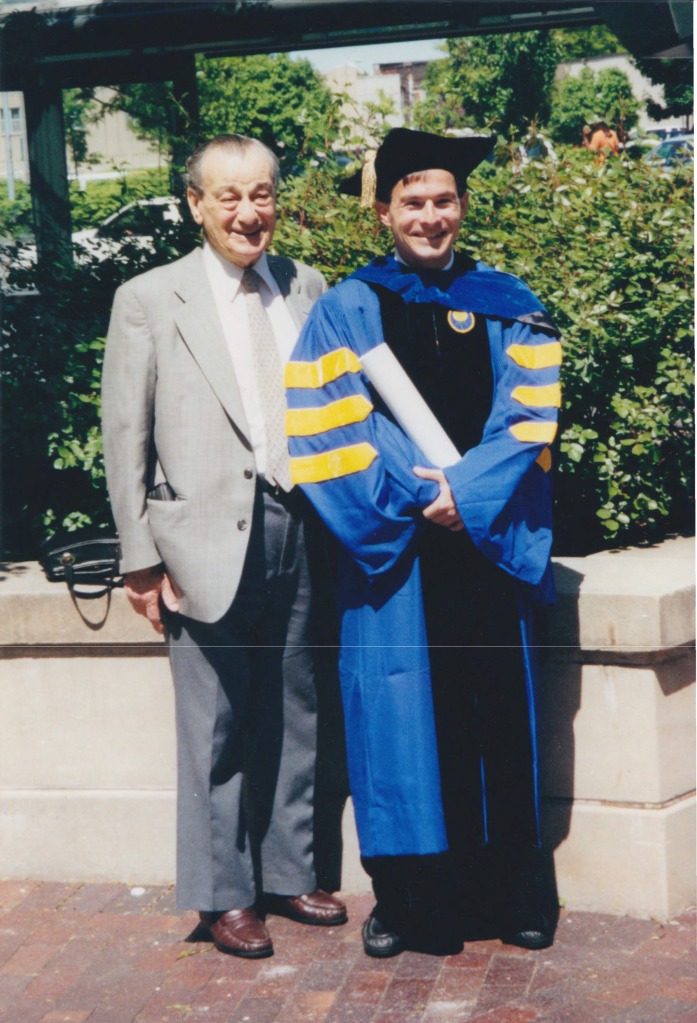

At that point, I was working as a postdoc with Emil while I waited for my paperwork to come through to travel abroad for a different postdoctoral job. I graduated in the summer of 2001, and of course have photos of that happy occasion.

I only did a couple of additional research papers with Emil once I left Rochester. I would’ve been happy to keep working with him more extensively, but he had new students to work with and lots of collaborators eager for his attention, so I was happy just to keep in touch and see him in Rochester and occasionally at meetings. In 2012, I saw him and Taco Visser at an OSA Frontiers in Optics meeting, and captured a delightful photo that captures the fact that Emil was not only a great scientist, but a fun person to be around.

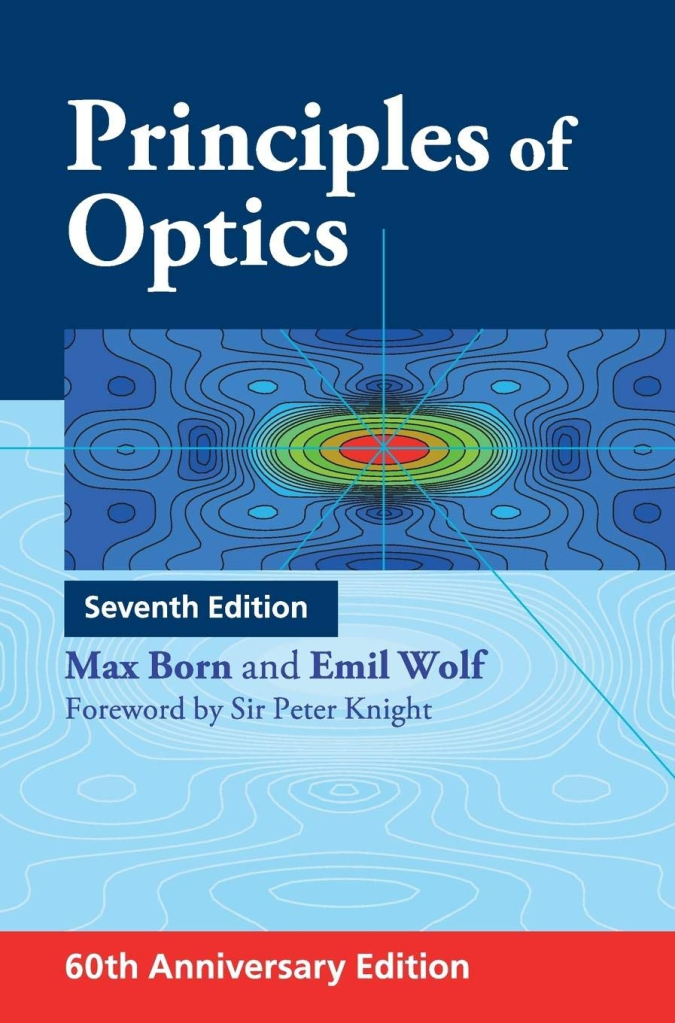

Emil passed away in 2018. In 2020, Cambridge released a 60th anniversary edition of Principles of Optics, including introductions from some luminaries in the optical sciences. I was asked, and volunteered, to reproduce the cover image once again with a different color palette.

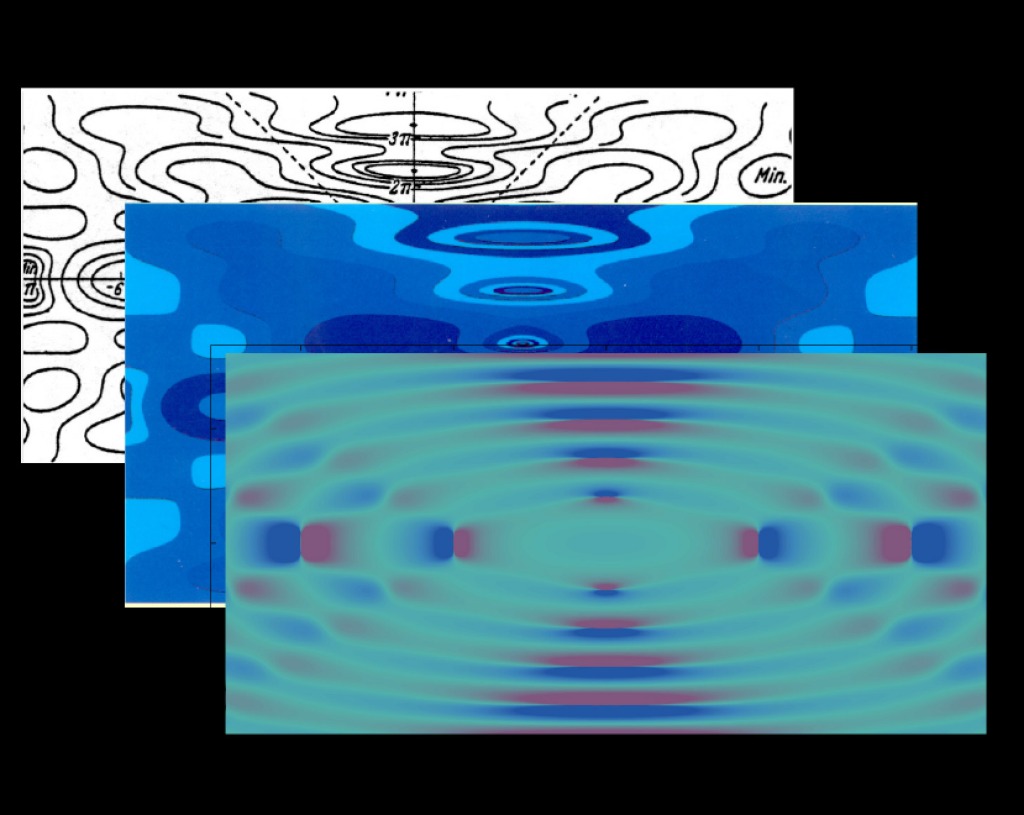

Originally, I was supposed to provide some explanation of the cover image for the text, but life got in the way and the book was published without my commentary. Let me instead provide some context based on a CD I did of Emil Wolf’s publications many years earlier, where I combined a few images from Emil’s focusing work to tell a story.

What I wrote about it:

The logo used on most of the pages of these collected papers represents both the scientific and technological advances that have progressed during Professor Wolf’s long and distinguished career.

The bottom image (black and white) is the schematic of the intensity of the field in the region of focus, as shown in Principles of Optics (section 8.8) or paper 27. This image, made in the pre-computer days, took Professor Wolf months to complete because of the complicated calculations involved.

The middle image (bluescale) is the intensity in the focal region as plotted by Professor P. Scott Carney (then a student) for the cover of the seventh edition of Principles of Optics . On computer, the calculation took less than an hour to complete.

The topmost image (red and blue) represents the mean frequency of the spectrum in the focal region of focused polychromatic light, which may be considered a generalization of the above-mentioned monochromatic case. This work (some of my own) may be seen in paper 319. Because of the more laborious calculations involved, this figure took over a week to generate on a computer dedicated to that purpose, a time much closer to the time it took to make the original intensity figure. So even though the technology has progressed rapidly, we continue to push its limits in pursuit of the answers to “deeper” questions.

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed this look back at some of my time with Emil. There’s even more discussion of my time with him in my book on Invisibility, since I worked with him on the subject.

Miss you, Emil!