Color can have surprising origins in nature. Most of the time, the color of an object is dictated by the light it absorbs: for example, if you see an object that is blue, that means that it reflects all the blue light shining on it and absorbs all the colors that aren’t blue. But colors can arise from completely different phenomena: rainbows, for example, arise due to the phenomenon of dispersion, i.e. that different colors of light are refracted differently within a raindrop.

Then we have the not-quite-a-rainbow spectrum of colors that one sees when oil is spread out over the surface of water, such as this photo that I took a few months ago in my neighborhood:

These arise from a completely different effect: wave interference! The oil forms a thin layer on top of the water, and wave interference from the oil-air interface and the oil-water interface can produce constructive interference for colors, depending on the thickness of the oil layer.

Oil slicks are an example of what is generally known as thin film optics, in which unusual optical effects are produced by putting one or more thin layers of material, usually comparable to the wavelength of light, onto a base layer. This is not only a phenomenon seen “in the wild,” in things like oil slicks, but is practically used in optical design and engineering!

Let’s take a basic look at thin film optics and how it can produce bright colors on reflection — or suppress them entirely.

We begin by considering a very practical problem: reducing the reflection of light from optical elements like lenses. Ideally, if one is creating an optical imaging system, such as a camera or a telescope, one wants as much of the light as possible to pass through the lens, and as little as possible to be reflected from it. This is a problem because, in general1, there is always some light that reflects when it interacts with a single interface.

For example, let us suppose we have a light wave incident head-on from air, with a refractive index of 1, to glass with a refractive index of 1.5. A simple calculation indicates that 4% of the light is reflected and 96% is transmitted. At first, this doesn’t seem like a big deal. But keep in mind that the same thing happens when the light wave exits the glass, so only 96% of the 96% makes it out, or 92% of the light comes out. (This is a little oversimplified, but gives the idea.)

92% transmission is just fine if you’ve got just one or two lenses, but if you’ve got an optical system with many elements, and you’re losing roughly 8% of the light at each element, the losses add up quickly. If we imagine just 3 elements, each with 92% transmission, then the light throughput ends up being just 78%. For applications where one is detecting very dim light, this can be a real problem.

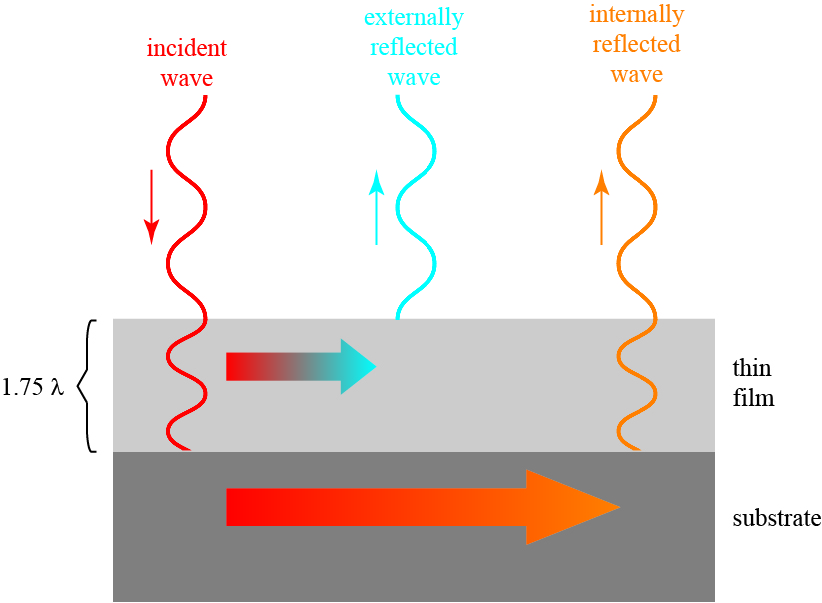

The most common solution to this problem is to coat the surface of the glass with a thin film of material with a different refractive index. If the thickness of the film and its refractive index are chosen properly, the reflected wave can be partially or totally canceled by complete destructive wave interference. This is illustrated below:

The idea is as follows: suppose the thickness of the thin film is chosen to be some odd multiple of a quarter wavelength of light. This could be 1/4, 3/4, 1 1/4, or 1 3/4, as chosen above (to make it easier to see). Part of the incident wave is directly reflected at the air-film interface, shown in blue; it so happens that, because it is reflecting off of a medium with a higher refractive index, the wave flips sign on reflection.

The rest of the incident wave enters the film and propagates to the substrate layer (a lens, to continue our example). Part of that wave reflects off of the substrate, shown in orange, and travels back out of the film; it also flips sign when it reflects off of the substrate, which is assumed to have a higher refractive index than the thin film.

These two waves, the directly reflected wave and the internally reflected wave, are “waving” in opposite directions, and will at least partly cancel each other out — the reflection is therefore suppressed! We have described what is called an antireflection coating in optics.

The thickness of the thin film is key in this. Because of that odd 1/4 wavelength thickness of the film, the light reflecting off of the substrate will travel an extra 1/2 wavelength compared to the wave that is directly reflected. This means that the two waves will be “out of phase,” and oppose each other.

Remarkably, the reflection can be canceled out perfectly. If we label the refractive index of air as n1 and the refractive index of the substrate as n3, it can be shown that the antireflection coating will work perfectly if its refractive index, n2, is given the value,

.

If n1 = 1 and n3 = 1.5, this tells us that the perfect antireflection coating will have n2 = 1.22.

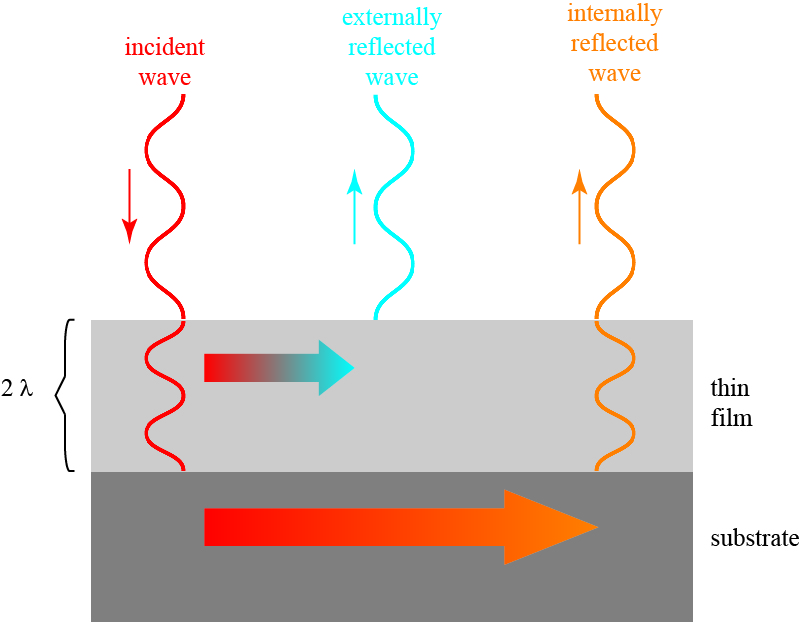

If we choose the thickness of the film a little differently, we can also enhance the reflection of light! If we increase the thickness of our film to be two wavelengths, we get a picture as follows.

Now the externally and internally reflected waves are in phase with each other, and the reflection is enhanced!

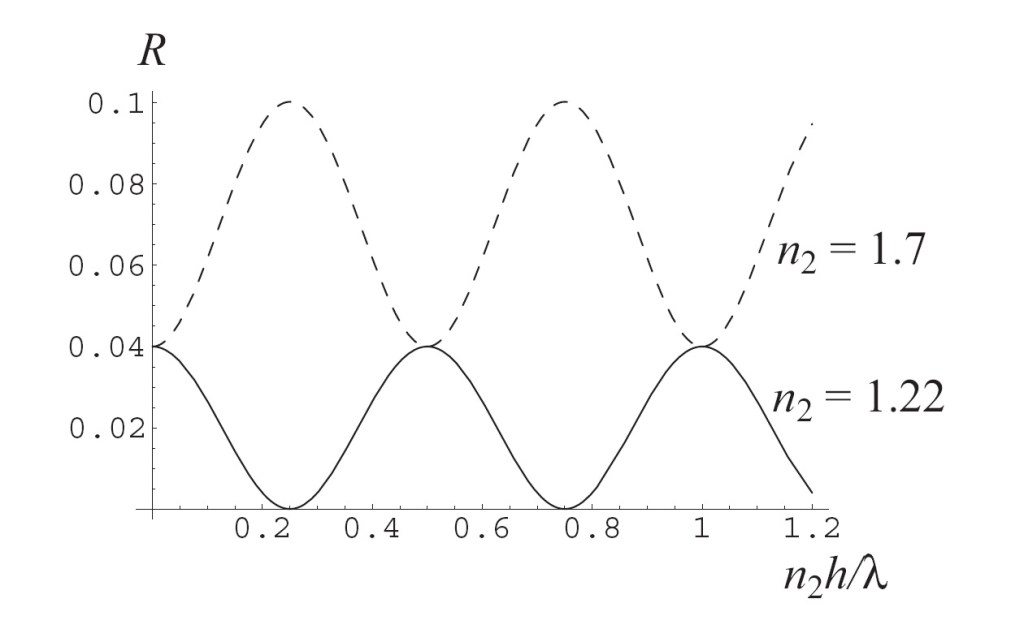

These two figures, taken together, show that the thickness of the film, relative to the wavelength, is crucially important. In fact, here is a figure I use to demonstrate antireflection/enhanced reflection as a function of optical thickness nh of the film relative to the wavelength λ.

This figure shows the reflectance R of a thin film relative to the thickness of the film and its refractive index. The outside medium is taken to be air, n1 = 1, and the substrate is taken to be crown glass, n3 = 1.55. You can see two big things in this figure: first, the choice of refractive index for the thin film matters a lot! For n2 = 1.22, we can achieve zero reflection; for n2 = 1.7, however, we get enhanced reflection! Also, we can see that the amount of light reflected depends on the relative thickness of the film compared to the wavelength.

What this means is that, for a given film, some colors will be very strongly reflected and other colors will not. This is the origin of the bright colors of an oil spot, as shown at the beginning of the post and shown again below for convenience:

The oil forms a circular spot floating on a thin film of water; presumably the oil layer is thicker near the center of the spot, and becomes thinner as you go to the edge of the spot. Because the colors reflected from the thin film depend on its thickness, we get a circular pattern of colors.

Thin film colors can appear in a lot of situations. Another example can be found in soap bubbles, which can show off bright colors when looked at from the right angles.

I’ve written about soap bubbles before, and how they played a remarkable role in demonstrating that atoms and molecules exist! Most of our previous discussion of the optics holds, but with one significant change: a soap bubble is a “free standing” thin film, and has air on both sides of it instead of a substrate. This results in the rules for enhanced and suppressed reflection being reversed; for example, a free standing film that is two wavelengths thick will now suppress reflection.

Thin film colors can be found in even more surprising places. The iridescent colors of many butterflies is due to thin films that have evolved in the wing structure; an example is Aglais io, the peacock butterfly.

The shimmering blue patches of the butterfly arise from thin film effects, basically a layer of thin scales on the wing. Why do they appear to shimmer, i.e. why are they iridescent? Thin film optics depends on the difference of optical path between the light wave that is externally reflected and the one that is internally reflected. If we change the angle at which we view the thin film, we effectively change the length of this path difference, which means different colors become enhanced/suppressed by the film. This iridescent effect appears to have evolved many times among a variety of different species, and it can be more complicated than a simple thin film. In general, colors that arise from the structure of a material instead of its chemical properties are known as — what else? — structural coloration.

These bright colors, however, can thwart our original plan of suppressing reflections in optical elements. A single thin film will suppress the reflection of some colors, and enhance others. This is fine if you’re doing an experiment with a laser of a single color, but if you’re trying to suppress reflection of many colors at once — for example in eyeglasses — then that strong color dependence is a problem.

What is the solution? Add more layers to the thin film! Roughly speaking, every additional layer of thin film added to a surface can be designed to suppress an additional color. I believe that most thin films applied to optical elements these days consist of multiple layers, and are designed to largely suppress reflections over the entire visible light spectrum. Animals, on the other hand, often evolve multilayer films to enhance certain combinations of colors.

If we add many, many layers, and have them repeat periodically, we come up with something even more unusual, what is nowadays referred to as a one-dimensional photonic crystal. However, we will defer that discussion for another day!

********************************************

- I say “in general” there is always some light that reflects because there is a Brewster angle at which one polarization of light will not reflect, and there are also magnetic materials that can be non-reflecting. But most natural materials, in most cases, will reflect some of the light shining upon them.

For a lens, we want to increase the proportion of transmitted light, right? Say we originally had 96% transmission, 4% reflection. So we add a coating that cancels reflected light by destructive interference. Great, now there’s no light reflected (ideally)!

But how does that increase the amount of transmitted light?

What am I missing here?

Hi there! Energy is conserved and, assuming there’s negligible absorption, the only options are transmission and reflection. If we eliminate reflection by destructive interference, the only place the light can go is to transmission.

I think I get it: it’s not that the reflected part of the light is getting cancelled by destructive interference, it’s that the light *can’t* be reflected due to the destructive interference. So it must be transmitted. Is this accurate?

Thanks for answering and clearing up my thinking!

That is more or less it! To put it in a more quantum sense, the “wave” part of the reflected light gets eliminated, so there’s no chance for a photon to be reflected, and it becomes transmitted with 100% probability.

“presumably the oil layer is thicker near the center of the spot, and becomes thinner as you go to the edge of the spot.”

Is there a reason that there are no bright colors in the center (thicker part) of the oil spot? Since interference only depends on phase difference, the colorful rings should appear across the entire oil spot, right?