So a few weeks ago I described a 1960 experimental test of time dilation in Einstein’s special theory of relativity that applies the Mössbauer effect to measure precise changes in the frequency of gamma rays. I only briefly described the Mössbauer effect in that post, and it’s a simple enough and interesting enough effect to elaborate upon in a separate post, so here we are!

In short, the Mössbauer effect is the absorption of a gamma ray by an atomic nucleus in a crystal such that the momentum of the gamma ray is absorbed by the entire crystal array, rather than the single nucleus that absorbed the gamma ray. Why this is significant is a longer story, which we now discuss.

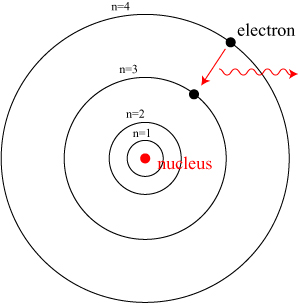

Let’s begin with a discussion of spectroscopy and how photons of different energies can be use to study different parts of the structure of atoms. I’ve talked many times about the Bohr model of the atom, usually pictured something like the image below.

In the days before we discovered quantum physics and the structure of the atom, researchers couldn’t understand why atoms seemed to absorb and emit light only at very specific discrete frequencies. Niels Bohr proposed a model of the atom in which electrons can only orbit the nucleus at special orbits, labeled by a number n, and would emit or absorb a single photon in jumping from one state to another.

This picture of electrons “orbiting” the nucleus would quickly be supplanted by a picture of electrons as extended waves enveloping the nucleus, but the basic principle introduced by Bohr — of discrete states for electrons and a discrete emission spectrum — holds up. People still use the term “orbits” to describe the states of the electron, despite its inaccuracy, because it gives a decent enough image.

The recognition that the absorption/emission spectrum of matter could be used to determine the structure of matter forms the basis of the field of spectroscopy.

Bohr’s work sought to explain the absorption and emission of visible light and ultraviolet light by atoms, which is caused by the transitions of the valence (outermost) electrons of the atoms. One can also study the behavior of electrons that lie in the inner orbits of the nucleus, the core electrons. For an atom with many electrons, much higher energy photons are needed to excite the core electrons, and X-rays are required. The field is then referred to as X-ray absorption spectroscopy. In an atomic nucleus, the energies are even higher, and emitted and absorbed photons are usually gamma rays.

Now is a good time to talk about the energy of photons (light particles)!

Light has wavelike and particlelike properties, which in a sense can be summarized by the formula that relates the energy E of a photon to the frequency f or wavelength λ of the associated wave, as

,

where “h” is the fundamental constant known as Planck’s constant and c is the speed of light in vacuum. Higher frequency photons have more energy. The energy of a photon is typically measured in “electron-volts,” the amount of energy an electron will get if accelerated through a potential of one volt.

A blue light photon, which has a wavelength of 450 nanometers, has an energy of 2.76 eV. X-rays, which have wavelengths between 10 nanometers and 0.01 nanometers, have photon energies between 124 eV and 124,000 eV, respectively. Gamma rays have wavelengths even shorter than X-rays, and can have photon energies into the millions of electron-volts.

The takeaway from this discussion is that X-ray photons have energies and momenta much greater than visible light, and gamma rays have energies and momenta much greater than X-rays. This means that, although they are all photons, they tend to have very different properties when interacting with matter. This observation will be important in a moment.

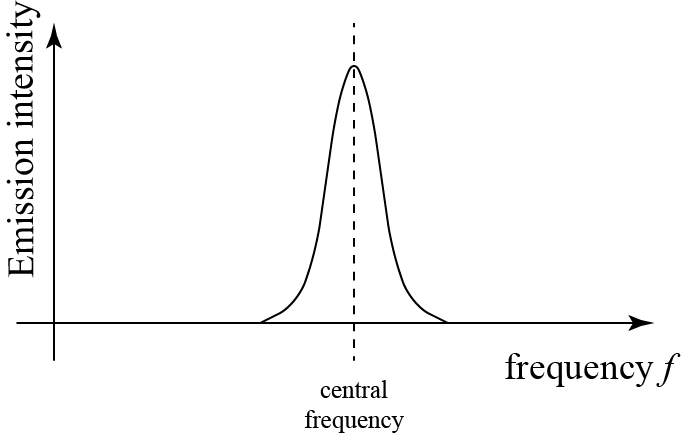

We have said that atoms emit and absorb photons at discrete spectral lines, i.e. single frequencies spaced out across the spectrum, but this isn’t quite true. Every atom absorbs and emits over a range of frequencies around each spectral line, which is called, depending on the circumstances, the absorption or emission spectrum.

If we were to measure the intensity of emitted light as a function of frequency, the picture might look something like the following figure.

The width of each spectral line is narrow and looked like, well, lines to those who first observed them, as they didn’t have measurements precise enough to discern the lineshape. The width of a spectral line is determined by a number of factors; these include Doppler shifts due to the random motion of the emitting atoms and natural line broadening due to the inherent quantum nature of the phenomenon.

The emission spectrum and the absorption spectrum of an atom or nucleus are complementary to each other: an atom/nucleus absorbs photons at the wave frequencies that it emits them. So if, for example, we use a sodium lamp to illuminate a sodium gas, we expect that the light will be strongly absorbed. This can be used to make one of the coolest experiments you’ll ever see: making black fire:

Because the absorption spectrum matches the emission spectrum, the fire strongly absorbs the sepia-colored sodium light, making it appear black!

A similar phenomenon was observed for X-ray spectroscopy: if one uses X-ray emissions from a particular material, those X-ray emissions will be strongly absorbed by the same material. But this does not happen for gamma rays! Assuming we have a nuclear transition in which element X becomes element Y with the emission of a gamma ray, you might expect that element Y would strongly absorb the gamma rays of element X, but it typically does not!

The reason for this can be found in the other conserved mechanical quantity in motion: momentum. Conservation of momentum traces back to Newton’s laws of motion, in particular Newton’s third law:

If two bodies exert forces on each other, these forces have the same magnitude but opposite directions.

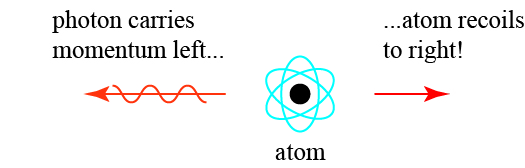

So if a free atom (in a gas, for example) emits a photon that travels to the left, the atom itself must get a “kick,” or recoil, to the right, as illustrated below.

There is also recoil when the atom absorbs a photon; the momentum of the absorbed photon must go somewhere, so it is also absorbed by the atom, which gets a kick.

But if an atom is put into motion by the emission by a photon, that means that the atom also carries kinetic energy. Because energy is conserved, this means that the emitted photon will, on average, have less energy than the energy associated with the spectral line. In practical terms, this means that the frequency of the emitted photon is lower than the frequency of the spectral line.

This happens again in absorption: because the atom recoils, it just take a little bit of the energy of the photon as kinetic energy, so the amount of energy absorbed internally by the atom is even lower!

Fortunately, this isn’t an issue for visible light. Photons, as massless particles, do not carry much momentum: when you open your front door on a sunny day, you do not get knocked backwards by sunlight! So for visible light, the amount of energy going to recoil is negligible.

The momentum of a photon is also directly proportional to its frequency, so the recoil experienced in X-ray emission and absorption is significantly larger. Here is where the spectral linewidth of absorption lines comes into play: because an atom can absorb light over a range of frequencies, as long as the frequency of the lower-energy photon lies within the linewidth, it can still be absorbed.

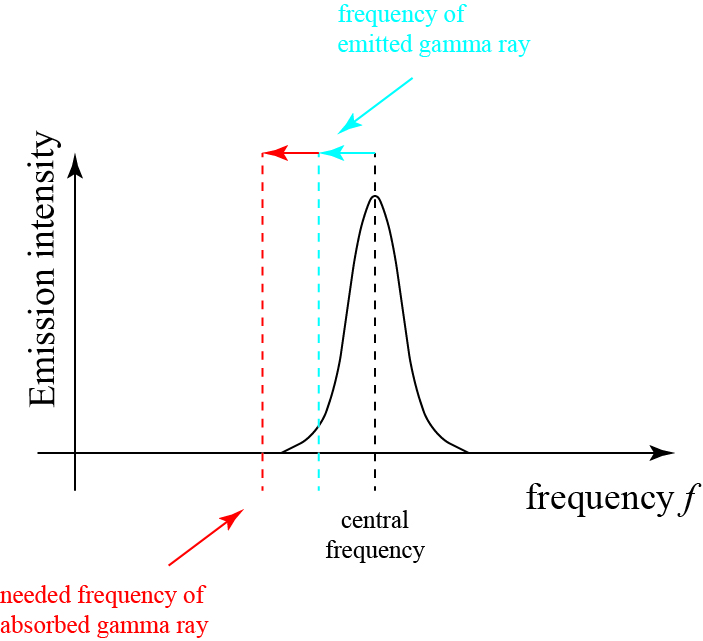

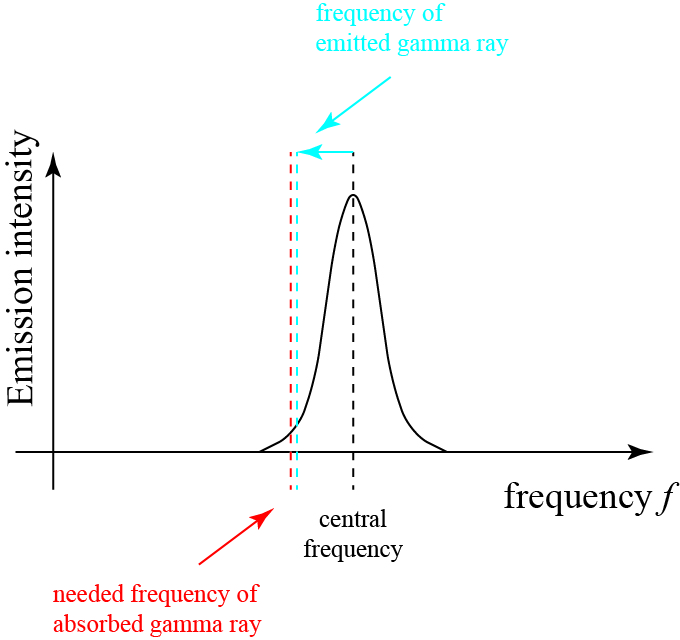

For gamma rays, which have even higher energy and momentum in general, the loss of energy resulting from the two recoils can move the frequency of the photon right out of the absorption spectrum, meaning that the photon cannot be absorbed at all! This is roughly illustrated below.

The photon loses energy when it is emitted by a nucleus, pushing its frequency down, but not out, of the spectral line. But in order to provide recoil to the absorbing nucleus to satisfy both energy and momentum conservation, it must give some of its energy up as recoil, reducing its frequency to a level where it no longer lies in the absorption spectrum of the nucleus! So, it ends up just… not being absorbed, which is what was seen in experiments.

This is where Rudolf Mössbauer and his eponymous effect come in! The first failed attempts to get resonant absorption of gamma rays were done with gases; Mössbauer instead looked at resonant absorption of gamma rays in crystalline solids, and found it!

Why would a solid be better at absorption gamma rays than a gas? In a gas, the atoms have little to no interaction with each other, so if a gamma ray is to be absorbed by an atom, the entire momentum of the gamma ray is transferred to the atom. In a crystalline solid, however, the atoms are all tightly bound together, and even though the gamma ray energy is absorbed by a single nucleus, the momentum can be transferred to the entire lattice instead. This involves a negligible change in velocity of the lattice, which means that the recoil kinetic energy is itself negligible.

To put this in equation form, suppose that p is the momentum of the photon, m is the mass of whatever absorbs the recoil, and v is the speed of the recoil; then momentum conservation says that

.

If m represents a single nucleus, and p is large, then v will be large as well. If the entire crystal lattice, consisting of 1000s of atoms or more, absorbs the recoil, then m will be 1000s of times larger and v will be 1000s of times smaller. If it is hard to visualize what I mean, imagine punching a punching bag versus punching the Earth. If you punch the low-mass bag, it moves; if you punch the Earth, it doesn’t move and you hurt your hand. In both cases, you transfer the same amount of momentum to your target, but the difference in mass makes all the difference.

Because the recoil is negligible, the frequency of the photon to be absorbed won’t change much, as illustrated below:

Now the dashed red line, which represents the frequency needed to be absorbed by a nucleus, remains within the absorption linewidth, and thus that photon can be absorbed by that resonance.

And though I have provided a lot of background information leading up to it, this is really all that there is to the Mössbauer effect: the recoil of gamma rays can, under certain circumstances, be absorbed by a crystal lattice rather than an individual nucleus, which means that very little energy goes to the recoil!

The Mössbauer effect has become an important tool in nuclear spectroscopy, and Mössbauer himself jointly won the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery, which he did as his PhD work.

This post is intended to be a relatively short introduction to the Mössbauer effect! One thing I did not do is describe the experiment that Mössbauer did to demonstrate his effect; I will leave that for a future post, after I do more translating of his paper in German!