I’ve been thinking again recently of the remarkable story of Julius Robert Mayer (1814-1878), the German physician and scientist who was the first person to truly discover the principle of conservation of energy. Most physicists associate James Prescott Joule with the discovery, though Joule in fact independently discovered the principle in 1843, a year after Mayer. I’ve written about Mayer’s life and work before in some detail, but today I wanted to focus on how Mayer’s life was nearly destroyed by political attacks on his work, and how he was saved by the truly outstanding and brilliant efforts of the Irish physicist John Tyndall in 1862.

First, let me briefly review the background. Mayer began his professional career as a medical doctor in 1840, but instead of setting up a private practice right away he opted to travel as a ship’s doctor on a vessel heading to the East Indies. In that day, bloodletting was still an accepted treatment for illness, and Mayer was struck by the fact that the venous blood of the sailors was bright red while in Indonesia, much more like arterial blood.

Mayer realized that the blood was redder because less oxygen was being used to heat the body in the warmer climate. This observation got him thinking about processes of cause and effect, and how effects must pass down from one event to another, sometimes in a way that could not easily be recognized. This was the impetus for the discovery of the conservation of energy.

Mayer pondered his ideas for some time, and finally in 1842 published his first paper on the subject, with the translated title, “Remarks upon the Forces of Inanimate Nature.” It is truly a beautiful piece of work, especially when one knows where it is leading. One passage that I particularly like from the paper:

Forces are causes : accordingly, we may in relation to them make full application of the principle — causa æquat effectum. If the cause c has the effect e, then c = e; if, in its turn, e is the cause of a second effect f, we have e = f, and so on: c = e = f … = c. In a chain of causes and effects, a term or a part of a term can never, as plainly appears from the nature of an equation, become equal to nothing. This first property of all causes we call their indestructibility.

In short, Mayer argues the cause-effect chain I mentioned above. Every force “causes” an “effect” to happen, and we can’t have a force act on something with no consequences — if we did, it wouldn’t be a physical force at all!

Mayer did more than just argue in vague philosophical terms. He correctly noted that heat must be the measurable effect of the random motion of atoms and molecules, and that heat can be created by macroscopic motion; for example, by shaking a bottle of water, one heats up the water. Even more importantly, he noted that heat can be turned back into mechanical motion, thus completing a statement of conservation of energy. Using published thermodynamic data from other researchers, Mayer went on to quantify the mechanical equivalent of heat: a measure of how a given change in temperature is related to an amount of mechanical work. His result was remarkably accurate.

Mayer’s work attracted little notice. He had published in a journal that was not a good audience for his work, and as a medical doctor he did not have scientific contacts who could help him spread the word of his discoveries. Then, in 1843, British brewer and scientist James Joule began presenting his own experimental work on conservation of energy. In a fit of nationalism, British scientists latched upon Joule’s work as a pure work of British ingenuity, and excluded any thought of sharing that credit with researchers from other countries. Joule himself, in a major work published in 1847, added criticism of Mayer’s discoveries, arguing that they were insignificant compared to his own. This led Mayer to fight back in print in 1848, leading to an extended argument in print.

At the same time, Mayer’s own life tragically took a turn for the worse. Two of his daughters died within days of each other in 1848. His critics did not provide him any respite, however, and continued to publish attacks on his scientific work. Mayer finally reached a breaking point in 1850: in a delirium, he fell from a third story window, severely injuring himself. His mental faculties declined further, and in 1852 he was involuntarily committed to an asylum, where he was given barbarous treatments. He was released in late 1853 and returned to limited medical practice, but withdrew from scientific discussion, largely a broken man.

Let us skip forward to 1862. The Great London Exposition, or International Exhibition of 1862, was planned to be held from May 1st to November 1st in South Kensington, London. Like most world’s fairs, it was intended to be a showcase of industry, technology and arts from around the world, and it ended up featuring a staggering 28,000 exhibitors from 30 countries.

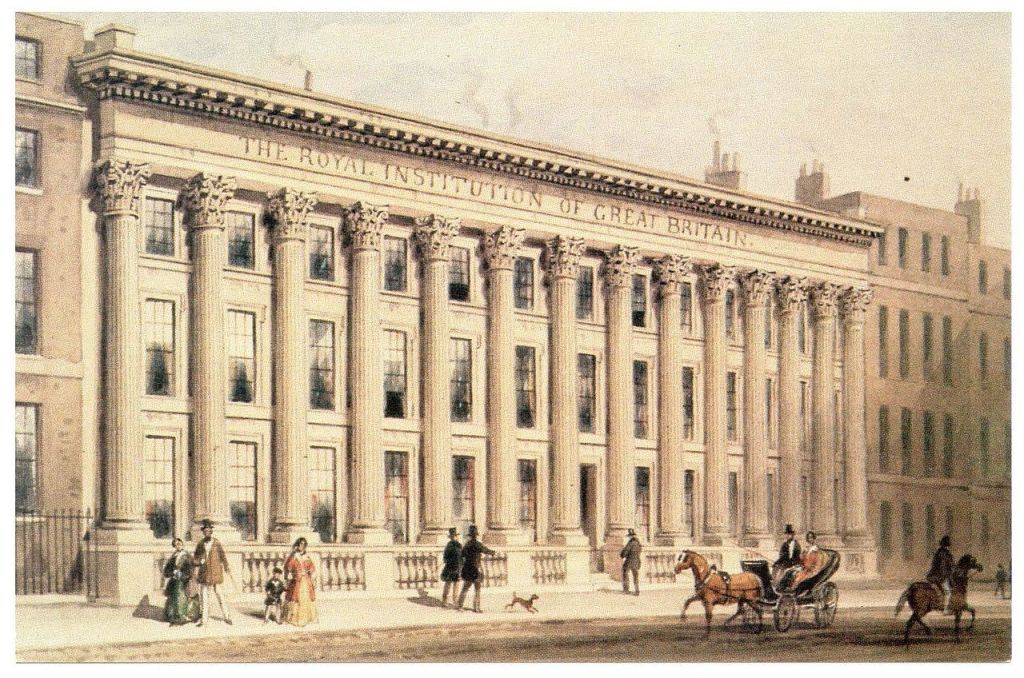

Like all such international events, the country hosting it wanted to put on a particularly good show, and the Honorary Secretary of the Royal Institution, Henry Bence Jones, suggested a series of Friday evening lectures on the scientific and technological strengths of England. The Irish physicist John Tyndall was asked to present a lecture “On Force,” which was then the term being used to describe concepts of energy and energy conservation.

By the time of his appointed task, Tyndall was already one of the world’s great physicists. He first rose to fame in the 1850s with studies of the phenomenon of diamagnetism, in which most ordinary materials are repelled weakly by a magnetic field. In 1856, he went on a scientific expedition the Alps and fell in love with mountain climbing, become a great climber. His time in the mountains also led him to study the motion of glaciers, and a number of glaciers around the world are now named after him. His observations on the heating properties of sunlight led him to perform experiments on how visible light and infrared light are absorbed by gasses, which resulted in him presenting in 1859 the first laboratory demonstration of what we call the greenhouse effect on Earth, in which visible light passes easily through the atmosphere but becomes trapped as thermal radiation.

Tyndall’s work made him one of the world’s recognized experts on heat, and in 1862 he prepared a series of lectures “Heat Considered as a Mode of Motion” for the Royal Institution. Tyndall had heard of Mayer, but had not had the opportunity to peruse his work; here, we let Tyndall himself explain what happened next (from the postscript to Tyndall’s lecture “On Force”):

While preparing for publication my last course of lectures on Heat, I wished to make myself acquainted with all that Mayer had done in connection with this subject . I accordingly wrote to two gentlemen who above all others seemed likely to give me the information which I needed. Both of them are Germans, and both particularly distinguished in connection with the Dynamical Theory of Heat. Each of them kindly furnished me with the list of Mayer’s publications, and one of them was so friendly as to order them from a bookseller, and to send them to me. This friend , in his reply to my first letter regarding Mayer, stated his belief that I should not find anything very important in Mayer’s writings ; but before forwarding the memoirs to me he read them himself. His letter accompanying the first of these papers, contains the following words :- ” I must here retract the statement in my last letter, that you would not find much matter of importance in Mayer’s writings : I am astonished at the multitude of beautiful and correct thoughts which they contain ; ” and he goes on to point out various important subjects, in the treatment of which Mayer had anticipated other eminent writers .

The friend in question was the German physicist Rudolf Clausius, himself now considered one of the founders of the theory of thermodynamics, that studies the relationship between work, heat, and temperature.

Tyndall in turn read Mayer’s papers and clearly concurred with Clausius’ assessment. It was evident that Mayer’s work had been unjustly neglected by the scientific community, and he resolved to do something about it. I can’t help but suspect that Tyndall was a bit appalled by the political push to claim all discoveries in energy for Great Britain. Tyndall himself was Irish, and though Great Britain and Ireland had been a “United Kingdom” since 1801, my impression that it was not a particularly amicable union. Ireland would eventually separated from the UK in 1922. I can imagine Tyndall reading Mayer’s papers, seeing how British scientists had suppressed and defamed them, and muttering “British nationalist bullshit” to himself.

On Friday, June 6, 1862, Tyndall presented his lecture “On Force” to the Royal Institution, in front of many of the most distinguished scientists in the country. The full lecture is about ten pages long, so we will not present it fully, but will share some of its highlights, though there are many of those! Tyndall begins by explaining the circumstances that led to his lecture:

THE existence of the International Exhibition suggested to our Honorary Secretary the idea of devoting the Friday evenings after Easter of the present year to discourses on the various agencies on which the material strength of England is based . He wished to make iron , coal, cotton, and kindred matters , the subjects of these discourses ; opening the series by a discourse on the Great Exhibition itself ; and he wished me to finish the series by a discourse on ” Force ” in general. For some months I thought over the subject at intervals , and had devised a plan of dealing with it ; but three weeks ago I was induced to swerve from this plan, for reasons which shall be made known towards the conclusion of the discourse .

Note the foreshadowing about the end of the lecture!

Tyndall opens the topic proper by a qualitative discussion of “force.” It should be noted that the distinction between “force” and “energy” was not yet solidified in science, so he uses the terms somewhat interchangeably. Today, we think of “force” as a “change in momentum,” and then indirectly a change in energy. Also note the very conversational and fun style of Tyndall’s lecture: the Royal Institution was (and is) an institution dedicated to presenting science to the public.

We all have ideas more or less distinct regarding force ; we know in a general way what muscular force means, and each of us would less willingly accept a blow from a pugilist than have his ears boxed by a lady. But these general ideas are not now sufficient for us ; we must learn how to express numerically the exact mechanical value of the two blows ; this is the first point to be cleared up.

Here, we are clearly talking about the modern conception of “force,” using a physical blow as a clear example of imparting a force upon another. (Though his view of ladies should have been more open-minded.)

We then get into some quantitative discussions of force:

A sphere of lead weighing 1lb. was suspended at a height of 16 feet above the theatre floor. It was liberated , and fell by gravity. That weight required exactly a second to fall to the earth from that elevation ; and the instant before it touched the earth , it had a velocity of 32 feet a second. That is to say, if at that instant the earth were annihilated , and its attraction annulled, the weight would proceed through space at the uniform velocity of 32 feet a second.

Suppose that instead of being pulled downward by gravity, the weight is cast upward in opposition to the force of gravity, with what velocity must it start from the earth’s surface in order to reach a height of 16 feet ? With a velocity of 32 feet a second. This velocity imparted to the weight by the human arm, or by any other mechanical means, would carry the weight up to the precise height from which it has fallen .

Here we get a simple example of a physical process that is in essence reversible: drop a lead sphere from 16 feet high, it will reach the floor with a speed of 32 feet per second. Throw the same sphere upward at 32 feet per second, it will reach a height of 16 feet. This is a strikingly symmetric process, and suggests something deeper going on.

Now the lifting of the weight may be regarded as so much mechanical work. I might place a ladder against the wall , and carry the weight up a height of 16 feet ; or I might draw it up to this height by means of a string and pulley, or I might suddenly jerk it up to a height of 16 feet. The amount of work done in all these cases, as far as the raising of the weight is concerned, would be absolutely the same. The absolute amount of work done depends solely upon two things : first of all , on the quantity of matter that is lifted ; and secondly, on the height to which it is lifted . If you call the quantity or mass of matter m , and the height through which it is lifted h, then the product of m into h, or mh, expresses the amount of work done.

Here we get our first definition of “work,” which is a form of energy. No matter how we lift the object up from the ground to a height h, we must exert a total work equal to mh. In modern terms, this formula is written mgh, where m is the mass, h is the height, and g is the acceleration of gravity, and the work is referred to as potential energy: energy that is in a loose sense “stored” in the object and has the potential to be released.

Supposing, now, that instead of imparting a velocity of 32 feet a second to the weight we impart twice this speed , or 64 feet a second . To what height will the weight rise ? You might be disposed to answer, ” To twice the height ; ” but this would be quite incorrect. Both theory and experiment inform us that the weight would rise to four times the height : instead of twice 16, or 32 feet , it would reach four times 16, or 64 feet. So also , if we treble the starting velocity, the weight would reach nine times the height ; if we quadruple the speed at starting, we attain sixteen times the height. Thus, with a velocity of 128 feet a second at starting, the weight would attain an elevation of 256 feet. Supposing we augment the velocity of starting seven times , we should raise the weight to 49 times the height, or to an elevation of 784 feet.

Here we get the recognition that the energy of a moving body is proportional to the square of its velocity, in what we call today the kinetic energy. Tyndall makes this an explicit statement:

Now the work done- or, as it is sometimes called , the mechanical effect– as before explained, is proportional to the height, and as a double velocity gives four times the height, a treble velocity nine times the height , and so on , it is perfectly plain that the mechanical effect increases as the square of the velocity. If the mass of the body be represented by the letter m, and its velocity by v, then the mechanical effect would be represented by m v² . In the case considered , I have supposed the weight to be cast upward , being opposed in its upward flight by the resistance of gravity ; but the same holds true if I send the projectile into water, mud, earth, timber, or other resisting material. If, for example, you double the velocity of a cannon-ball , you quadruple its mechanical effect. Hence the importance of augmenting the velocity of a projectile, and hence the philosophy of Sir William Armstrong in using a 50 lb. charge of powder in his recent striking experiments. The measure then of mechanical effect is the mass of the body multiplied by the square of its velocity.

The modern formula for kinetic energy is in fact mv2/2, one half of Tyndall’s value.

Now we get a lengthy passage, but one that is key to the entire discussion of conservation of energy:

Now in firing a ball against a target the projectile, after collision , is often found hissing hot. Mr. Fairbairn informs me that in the experiments at Shoeburyness it is a common thing to see a flash of light , even in broad day, when the ball strikes the target. And if I examine my lead weight after it has fallen from a height I also find it heated . Now here experiment and reasoning lead us to the remarkable law that the amount of heat generated , like the mechanical effect, is proportional to the product of the mass into the square of the velocity. Double your mass, other things being equal, and you double your amount of heat ; double your velocity, other things remaining equal, and you quadruple your amount of heat . Here then we have common mechanical motion destroyed and heat produced . I take this violin bow and draw it across this string . You hear the sound . That sound is due to motion imparted to the air , and to produce that motion a certain portion of the muscular force of my arm must be expended . We may here correctly say , that the mechanical force of my arm is converted into music. And in a similar way we say that the impeded motion of our descending weight , or of the arrested cannon- ball , is converted into heat. The mode of motion changes, but it still continues motion ; the motion of the mass is converted into a motion of the atoms of the mass ; and these small motions , communicated to the nerves , produce the sensation which we call heat. We, moreover, know the amount of heat which a given amount of mechanical force can develope . Our lead ball , for example, in falling to the earth generated a quantity of heat sufficient to raise the temperature of its own mass three- fifths of a Fahrenheit degree. It reached the earth with a velocity of 32 feet a second, and forty times this velocity would be a small one for a rifle bullet ; multiplying this by the square of 40, we find that the amount of heat developed by collision with the target would, if wholly concentrated in the lead, raise its temperature 960 degrees. This would be more than sufficient to fuse the lead. In reality , however, the heat developed is divided between the lead and the body against which it strikes ; nevertheless, it would be worth while to pay attention to this point and to ascertain whether rifle bullets do not , under some circumstances , show signs of fusion .

Conservation of energy took a long time to recognize because, in day to day life, things regularly seem to just stop moving. If we drop a mass from a height, as Tyndall discussed earlier, that object stops moving when it hits the ground. If we fire a bullet at a target, the bullet stops moving. But we are missing that things do get set into motion: we hear a sound when the bullet hits the target, which is the motion of air molecules, and we feel the heat of the bullet and target, which is the random motion of the atoms and molecules of those objects. It is evidently even possible to see a flash of light, which is the motion of the bullet converted into electromagnetic waves! Mayer’s conception of “every cause has an effect” holds, though we cannot directly see many of the effects in an impact.

The recognition of this universal law suddenly opens the door to linking all sorts of phenomena, as Tyndall continues:

From the motion of sensible masses, by gravity and other means, the speaker passed to the motion of atoms towards each other by chemical affinity. A collodion balloon filled with a mixture of chlorine and hydrogen was hung in the focus of a parabolic mirror, and in the focus of a second mirror 20 ft . distant a strong electric light was suddenly generated ; the instant the light fell upon the balloon , the atoms within it fell together with explosion, and hydro-chloric acid was the result. The burning of charcoal in oxygen was an old experiment, but it had now a significance beyond what it used to have ; we now regard the act of combination on the part of the atoms of oxygen and coal exactly as we regard the clashing of a falling weight against the earth . And the heat produced in both cases is referable to a common cause. This glowing diamond, which burns in oxygen as a star of white light , glows and burns in consequence of the falling of the atoms of oxygen against it. And could we measure the velocity of the atoms when they clash, and could we find their number and weight, multiplying the mass of each atom by the square of its velocity, and adding all together, we should get a number representing the exact amount of heat developed by the union of the oxygen and carbon .

In short, the “cause-effect” chain applies to chemical reactions as well! With a bright light source, a chemical reaction creating hydrochloric acid could be induced, “the motion of atoms towards each other.”

Tyndall then turns to the most important connection to complete a theory of conservation of energy: the conversion of heat into mechanical work:

Thus far we have regarded the heat developed by the clashing of sensible masses and of atoms. Work is expended in giving motion to these atoms or masses, and heat is developed . But we reverse this process daily , and by the expenditure of heat execute work. We can raise a weight by heat ; and in this agent we possess an enormous store of mechanical power. This pound of coal, which I hold in my hand , produces by its combination with oxygen an amount of heat which, if mechanically applied, would suffice to raise a weight of 100 lbs . to a height of 20 miles above the earth’s surface. Conversely, 100 lbs . falling from a height of 20 miles , and striking against the earth , would generate an amount of heat equal to that developed by the combustion of a pound of coal . Wherever work is done by heat, heat disappears . A gun which fires a ball is less heated than one which fires blank cartridge. The quantity of heat communicated to the boiler of a working steam -engine is greater than that which could be obtained from the re-condensation of the steam after it had done its work ; and the amount of work performed is the exact equivalent of the amount of heat lost. Mr. Smyth informed us in his interesting discourse , that we dig annually 84 millions of tons of coal from our pits. The amount of mechanical force represented by this quantity of coal seems perfectly fabulous. The combustion of a single pound of coal , supposing it to take place in a minute, would be equivalent to the work of 300 horses ; and if we suppose 108 millions of horses working day and night with unimpaired strength , for a year, their united energies would enable them to perform an amount of work just equivalent to that which the annual produce of our coal -fields would be able to accomplish.

This recognition of the mechanical equivalent of heat is key to understanding the workings and limitations of steam engines and internal combustion engines. We can only get as much work out of a substance like coal that is already stored within it.

The recognition that energy is conserved drew renewed attention to other physical problems, in surprising areas:

Let us now turn our thoughts for a moment from the earth towards the sun. The researches of Sir John Herschel and M. Pouillet have informed us of the annual expenditure of the sun as regards heat ; and by an easy calculation we ascertain the precise amount of the expenditure which falls to the share of our planet. Out of 2300 million parts of light and heat the earth receives one. The whole heat emitted by the sun in a minute would be competent to boil 12,000 millions of cubic miles of ice- cold water. How is this enormous loss made good ? Whence is the sun’s heat derived, and by what means is it maintained ? No combustion, no chemical affinity with which we are acquainted would be competent to produce the temperature of the sun’s surface. Besides, were the sun a burning body merely, its light and heat would assuredly speedily come to an end.

The final two sentences might be considered foreshadowing the future of physics. Of course, we now know that the sun generates its energy through nuclear fusion, enabled by the strong gravitational forces within. Many had wondered about the origin of the sun’s light and heat before, but the discovery of conservation of energy put the problem in a new light.

What agency then can produce the temperature and maintain the outlay ? We have already regarded the case of a body falling from a great distance towards the earth, and found that the heat generated by its collision would be twice that produced by the combustion of an equal weight of coal . How much greater must be the heat developed by a body falling towards the sun ! The maximum velocity with which a body can strike the earth is about 7 miles in a second ; the maximum velocity with which it can strike the sun is 390 miles in a second . And as the heat developed by the collision is proportional to the square of the velocity destroyed , an asteroid falling into the sun with the above velocity would generate about 10,000 times the quantity of heat generated by the combustion of an asteroid of coal of the same weight. Have we any reason to believe that such bodies exist in space, and that they may be raining down upon the sun ? The meteorites flashing through the air are small planetary bodies, drawn by the earth’s attraction, and entering our atmosphere with planetary velocity. By friction against the air they are raised to incandescence and caused to emit light and heat. At certain seasons of the year they shower down upon us in great numbers. In Boston 240,000 of them were observed in nine hours. There is no reason to suppose that the planetary system is limited to ” vast masses of enormous weight ; ” there is every reason to believe that space is stocked with smaller masses, which obey the same laws as the large ones. That lenticular envelope which surrounds the sun, and which is known to astronomers as the Zodiacal light, is probably a crowd of meteors ; and moving as they do in a resisting medium they must continually approach the sun . Falling into it, they would be competent to produce the heat observed , and this would constitute a source from which the annual loss of heat would be made good.

Before the discovery of nuclear fusion, a “meteor hypothesis” was introduced, suggesting that the continual crashing of meteors into the sun could generate enough heat to keep it burning. In the above passage, Tyndall notes that the energy of a meteor crashing into the sun could be considerable. The meteor hypothesis did not last, of course, but it was independently suggested by a number of researchers, with Marey among the earliest.

I share this next passage simply because it is a fun bit of science trivia that could be used as a classroom example on kinetic energy:

Our earth moves in its orbit with a velocity of 68,040 miles an hour. Were this motion stopped, an amount of heat would be developed sufficient to raise the temperature of a globe of lead of the same size as the earth 384,000 degrees of the centigrade thermometer. It has been prophesied that ” the elements shall melt with fervent heat.” The earth’s own motion embraces the conditions of fulfilment ; stop that motion , and the greater part , if not the whole, of her mass would be reduced to vapour. If the earth fell into the sun, the amount of heat developed by the shock would be equal to that developed by the combustion of 6435 earths of solid coal.

Tyndall continues by looking at the flow of water on the Earth. He notes that the tides are produced by gravity, and effectively have a braking effect on the motion of the Earth, whereas rivers and streams are formed by water evaporated by sunlight. He then makes the following fascinating observation:

Supposing then that we turn a mill by the action of the tide , and produce heat by the friction of the millstones ; that heat has an origin totally different from the heat produced by another mill which is turned by a mountain stream . The former is produced at the expense of the earth’s rotation, the latter at the expense of the sun’s radiation .

He is saying, in essence, that two devices that get their motion from flowing water actually get their energy from distinct sources!

But energy connects everything, and leads us to look at how plants are in fact receiving energy from the sun:

Trees and vegetables grow upon the earth , and when burned they give rise to heat, and hence to mechanical energy. Whence is this power derived ? You see this oxide of iron, produced by the falling together of the atoms of iron and oxygen ; here also is a transparent gas which you cannot now see— carbonic acid gas-which is formed by the falling together of carbon and oxygen. These atoms thus in close union resemble our lead weight while resting on the earth ; but I can wind up the weight and prepare it for another fall, and so these atoms can be wound up, separated from each other, and thus enabled to repeat the process of combination . In the building of plants carbonic acid is the material from which the carbon of the plant is derived ; and the solar beam is the agent which tears the atoms asunder, setting the oxygen free, and allowing the carbon to aggregate in woody fibre. Let the solar rays fall upon a surface of sand ; the sand is heated , and finally radiates away as much heat as it receives ; let the same beams fall upon a forest, the quantity of heat given back is less than the forest receives, for the energy of a portion of the sunbeams is invested in building up the trees in the manner indicated .

In photosynthesis, plants use sunlight to break up CO2 and release oxygen. The amount of energy radiated away from a forest is therefore less than the energy that illuminated it. In concluding, Tyndall notes that we are then, in turn, beneficiaries of the sun:

But we cannot stop at vegetable life, for this is the source, mediate or immediate, of all animal life . The sun severs the carbon from its oxygen ; the animal consumes the vegetable thus formed , and in its arteries a reunion of the severed elements take place, and produce animal heat. Thus, strictly speaking , the process of building a vegetable is one of winding up ; the process of building an animal is one of running down. The warmth of our bodies, and every mechanical energy which we exert, trace their lineage directly to the sun. The fight of a pair of pugilists, the motion of an army, or the lifting of his own body up mountain slopes by an Alpine climber, are all cases of mechanical energy drawn from the sun. Not, therefore, in a poetical , but in a purely mechanical sense , are we children of the sun.

I have gotten so distracted by Tyndall’s poetic lecture that the reader may have lost track of the whole point of this post! Remember that Tyndall was speaking at the Royal Institution, during the International Exhibition, presumably a source of nationalistic pride for all in the United Kingdom, just as British scientists took nationalistic pride in claiming that all the important work on heat and energy had been done by British researchers. Tyndall wrapped up his lecture as follows:

I might extend these considerations ; the work, indeed , is done to my hand-but I am warned that I have kept you already too long. To whom then are we indebted for the striking generalizations of this evening’s discourse ? All that I have laid before you is the work of a man of whom you have scarcely ever heard. All that I have brought before you has been taken from the labours of a German physician , named Mayer. Without external stimulus , and pursuing his profession as town physician in Heilbronn, this man was the first to raise the conception of the interaction of natural forces to clearness in his own mind. And yet he is scarcely ever heard of in scientific lectures, and even to scientific men his merits are but partially known . Led by his own beautiful researches, and quite independent of Mayer, Mr. Joule published his first Paper on the Mechanical Value of Heat,’ in 1843 ; but in 1842 Mayer had actually calculated the mechanical equivalent of heat from data which a man of rare originality alone could turn to account. From the velocity of sound in air Mayer determined the mechanical equivalent of heat. In 1845 he published his Memoir on ‘ Organic Motion ,’ and applied the mechanical theory of heat in the most fearless and precise manner to vital processes . He also embraced the other natural agents in his chain of conservation. In 1853 Mr. Waterston proposed, independently, the meteoric theory of the sun’s heat, and in 1854 Professor William Thomson applied his admirable mathematical powers to the development of the theory ; but six years previously the subject had been handled in a masterly manner by Mayer, and all that I have said on this subject has been derived from him . When we consider the circumstances of Mayer’s life , and the period at which he wrote, we cannot fail to be struck with astonishment at what he has accomplished . Here was a man of genius working in silence , animated solely by a love of his subject, and arriving at the most important results, some time in advance of those whose lives were entirely devoted to Natural Philosophy. It was the accident of bleeding a feverish patient at Java in 1840 that led Mayer to speculate on these subjects. He noticed that the venous blood in the tropics was of a much brighter red than in colder latitudes, and his reasoning on this fact led him into the laboratory of natural forces, where he has worked with such signal ability and success . Well , you will desire to know what has become of this man. His mind gave way ; he became insane, and he was sent to a lunatic asylum. In a biographical dictionary of his country it is stated that he died there ; but this is incorrect . He recovered ; and, I believe , is at this moment a cultivator of vineyards in Heilbronn .

Emphasis mine! In front of all his colleagues, Tyndall brought forth the name of Julius Robert Mayer, who his colleagues had worked to malign for years! This was a total hero move on the part of Tyndall, in my opinion, and I find it simply amazing.

Among those who took objection to Tyndall’s glorious defense of Mayer were prominent physicists William Thomson and Peter Guthrie Tait, who in late 1862 wrote an article in volume 3 of the magazine Good Words about “Energy.” This article explicitly uses the term “conservation of energy,” perhaps the first time, as the authors snarkily admit in their introduction might cause some confusion for casual readers:

THE non-scientific reader who may take up this article in the expectation of finding an exhortation to manly sports, or a life of continual activity, with corresponding censure of every form of sloth and sensual indulgence, will probably be inclined to throw it down when he finds that it is devoted to a question of physical science.

In an otherwise charming article, Thomson and Tait launch into another criticism of Mayer’s work, clearly sparked by Tyndall’s lecture:

On the strength of this publication an attempt has been made to claim for Mayer the credit of being the first to establish in its generality the principle of the Conservation of Energy. It is true that “La science n’a pas de patrie,” and it is highly creditable to British philosophers, that they have so liberally acted according to this maxim. But it is not to be imagined that on this account there should be no scientific patriotism, or that in our desire to do all justice to a foreigner, we should depreciate or suppress the claims of our own countrymen. And it especially startles us that the recent attempts to place Mayer in a position which he never claimed, and which had long before been taken by another, should have found support within the very walls wherein Davy propounded his transcendent discoveries.

This is very funny to me, in that Thomson and Tait argue that they’re not denouncing Mayer out of patriotism, and that they just had to do it… for science!

This started a fierce back and forth in scientific journals between Tyndall and Thomson and Tait, but Tyndall was more than up to the challenge. A lovely summary of it comes from a later article in The Popular Science Monthly:

We have no space to go further into the particulars of this controversy, which was as discreditable to the assailants of Mayer as it was honorable to his disinterested defender. It is to be remembered that on all occasions, and in the most emphatic way, Professor Tyndall bore his testimony to the greatness of Dr. Joule’s work, and deprecated every construction of his efforts which assumed that he was exalting the German at the expense of the Englishman. His demand was that Dr. Mayer be accorded a distinguished place among the founders of the modern doctrine of forces—such a place as he was incontestably entitled to by the scope, originality, and earliness of his work. But his opponents would allow the German doctor no merit whatever as a pioneer or discoverer, and no place in the circle of eminent men who created the new epoch of dynamical philosophy. The attack, however, upon Mayer signally failed of its intended purpose, and the parties who made it had the mortification of seeing that their ungenerous exertions were overruled to an end very different from that which they had designed. After the sifting and probing which followed the onslaught of the Scotchmen, the claims in behalf of Mayer were universally recognized as just; he was chosen by acclamation a member of the French Academy of Sciences, and the award of the Copley medal in 1871, the highest honor in the gift of the Royal Society of England, was the sharp rebuke of British Science to the unworthy efforts incited by a spurious patriotism to depreciate an illustrious foreign savant.

It is fair, however, to note that Mayer still is not as well-known as Joule. But his work is recognized and, most important to me, he received significant recognition during his lifetime. From the same article, we learn:

Dr. Mayer, as we have intimated, was a man of much suffering, which was undoubtedly aggravated by the neglect and injustice with which his labors were treated ; and, when generous recognition of his services was made, the good effect on his disordered mind was palpable. It was while he was in the asylum, under treatment, that the Copley medal with Tyndall’s accompanying letter was put into his hands. Dr. Miilburger, the attending physician, remarked, ” I can still see him as he entered my room, beaming with gladness, to exhibit to me this rare distinction.”

The article concludes “A monument is to be erected to Mayer at Heilbronn, and the scientific men of different countries are adding their contributions to those of his townsmen for the purpose of its erection,” and that monument was built and still stands in Heilbronn today.

********************************

Some information for this post came from the article “Julius Robert Mayer,” The Popular Science Monthly 15 (1879), 397-410.