Some exciting personal and optics news: I just had a paper published in the prestigious journal Optica with my student Wenrui Miao and my colleague Yongtao Zhang on “Deterministic vortices evolving from partially coherent fields.” The paper is open access, so you can read it for free from anywhere, if you are so interested.

Optica has a rather high standard for publication — your work has to be considered broadly significant to optics and, obviously, well presented and correct. So this is a big deal for me, and I thought I would share a short non-technical description of what the paper is about!

So, this paper is about mixing two subfields of optics: coherence theory and singular optics, which are two of my theoretical specialties. Let’s start with a little discussion of singular optics. Light is a wave, and if you try to visualize a wave, you will most likely imagine something like shown below.

We have a snapshot in time here of a wave like a wave on a string, with repeated wiggles up and down as it travels to the right. If it oscillates at a single frequency, it is known as a monochromatic (“single color”) wave, and in much of optics we study waves that are at least approximately monochromatic. This works for lasers, but not with normal light sources like light bulbs or the sun — more on this momentarily.

At any moment of time at any point of space, a monochromatic wave will be at some point of its up-down cycle, and we refer to that as the “phase.” The phase is usually described as an angle, and one cycle is a full 360 degrees. Those locations where the wave has phase of zero are usually referred to as the wavefronts of the wave.

So this is a good way to describe waves in one-dimension, like a string, but what does a light wave in three-dimensional space look like? Most of the time, a light wave can be described, at least in a small region of space, as a series of planar wavefronts, and this ideal situation is referred to as a plane wave.

But it is possible to have a wave where the wavefronts are twisted together to form a screw-like structure; this structure is usually referred to as an optical vortex, because it circulates around the central axis.

On that line around which the wavefronts circulate, the intensity of light is zero, and the phase is undefined, or singular. This is the origin of the name “singular optics,” which is the study of the optics and applications of optical vortices and other wavefield singularities.

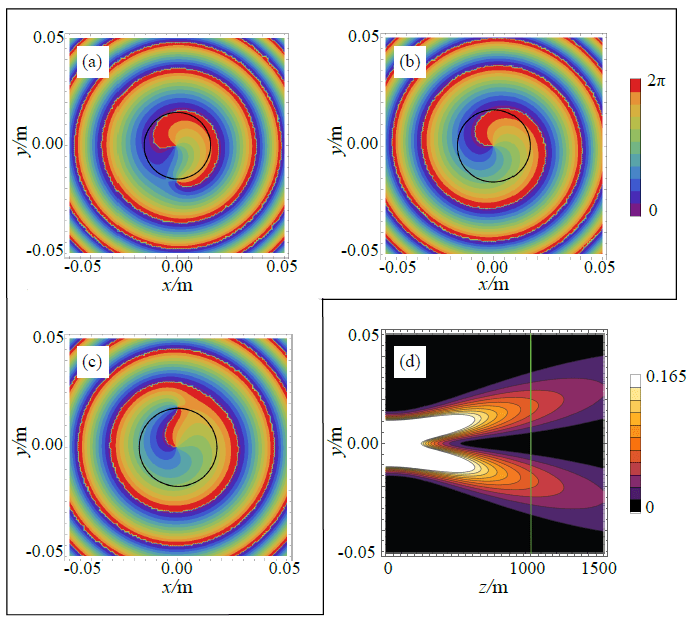

It is rather inconvenient to draw three-dimensional images of optical vortices, and usually we measure the properties of a light wave in an planar detector. If we look at a cross-sectional view of the vortex phase, it looks something as follows.

Now the phase is shown as a color, from black to white. This is another wave to visualize the phase structure of a vortex acting like a “ramp.”

Vortex beams have been considered as a means to increase the amount of data transmitted in optical communication systems. Vortices always have an integer-valued “twist” to them, and vortex beams of different twists can be combined, allowing information transmitted simultaneously on different vortex beams.

One problem with this plan, however, is in free-space optical communications. Light waves that pass through the atmosphere will get distorted by atmospheric turbulence, and that will distort the phase of the light wave, distorting the vortex in turn, which is a phase structure. One might wonder if there is a way to make a light beam more resistant to fluctuations of phase induced by turbulence.

This is where coherence theory comes in! Most natural light waves have some random fluctuations in them due to a variety of effects, making their phase partially random in both space and time. A wave that is perfectly monochromatic is called coherent, and a wave that has some fluctuations is called partially coherent. One can only characterize light waves with random fluctuations by mixing statistics and optics, and this is the subject known as coherence theory.

Though coherence theory was originally developed to characterize the properties of natural light sources, it is also possible to design a partially coherent light beam with tailored coherence properties. Such beams have been shown to be more resistant to the effects of atmospheric turbulence because they are “pre-randomized” in a controlled way.

The next natural question to ask is whether it is possible to combine optical vortices and partial coherence to make beams that have vortices for communication and more resistant to turbulence. But there’s a problem: a vortex is a phase structure of a field, and a partially coherent beam has a phase which is at least partially randomized, ruining the vortex! It has been shown that in most situations, if you try to impart a vortex on a partially coherent field, or you try to make a coherent vortex field partially coherent, the vortex structure is more or less lost on propagation!

But in our paper, we show that this isn’t always the case! You can design a partially coherent beam which possesses no definite vortex at the source, but evolves one as it propagates to a specified distance! An example of this in action is shown below, from the paper.

The beam is designed to create a perfect vortex in the beam center at 1000 meters; parts a, b and c of the figure show the phase of the beam at 920 m, 1000 m, and 1080 m. In a and c, there are actually two vortices present, which are not ordinary vortices but vortices in the correlation of the beam. Only in b do we have a single vortex right in the middle of the beam. Part d shows the intensity of the beam on propagation, and how it spreads and develops the zero of intensity in its core on propagation.

This was a surprising result: it was generally assumed, I believe, that vortices will always be destroyed on propagation, but we showed that they can sometimes evolve naturally in a partially coherent beam, if the beam is carefully designed!

The next question is whether such a beam will perform better and carry a vortex better through atmospheric turbulence! That is a question that we are trying to answer now…