I’ve mentioned before that I’ve started to experiment with doing history of science TikToks for fun, and did one not long ago about Frank Perret’s brush with death in the path of a pyroclastic flow on Mount Pelée somewhere around 1930:

This video was based on a post I did on my Science Chamber of Horrors Tumblr ages ago on “Frank Versus the Volcano,” and in the process of prepping the video I had to track down my original source for Perret’s story, which is his 1937 monograph on his observations of Mt. Pelée from 1929-1932.

The digital copy of the book wasn’t that great, as many of the photographs had bad scanning artifacts, and that got me thinking: how much would it cost to get an original copy of Perret’s monograph? The answer, as it turns out, is about $25, so I couldn’t resist picking one up and sharing some of the original images here!

First, let me give a little background for those who haven’t watched the video and don’t like getting their information from videos! Mt. Pelée is on the island of Martinique in the Caribbean, and in 1902, after several years of rumblings, it erupted in full force, sending a deadly pyroclastic flow down the mountain towards the city of St. Pierre. A pyroclastic flow is a superheated cloud of ash and gas, and can be devastatingly deadly; it was to the people of St. Pierre, who were almost entirely wiped out in an instant by the flow, some 30,000 people. (Only three people survived who were arguably in or near the city itself.)

The eruption and devastation of Pelée was a shock, because nobody knew that volcanos could do such a thing. The people of St. Pierre were understandably nervous before the eruption, but they believed they were far enough from the volcano to avoid, or at least be able to outrun, the worst of its effects. The tragedy marks the beginning of the modern science of volcanology, as researchers rushed to understand volcanos better.

Frank Perret (1867-1943) would become one of the new researchers, though he would enter the field through a twist of fate and luck. Perret was born in Connecticut and studied physics at the Polytechnic Institute of New York City, finding employment in the laboratories of Thomas Edison after graduation working on engines and dynamos. He eventually used his knowledge to co-found his own company, the Elektron Manufacturing Company, which apparently became quite successful.

The stress of the job took its toll on Parret, however, and he suffered from “nervous prostration caused by overwork” in 1902, the same year that Pelée had its deadly eruption. His doctor suggested that he take an extended stay in Italy to recuperate, and he went to Naples, within sight of Mount Vesuvius, the active volcano that infamously destroyed and buried Pompeii. The intrigued Perret turned to volcanology as his new passion, and made the acquaintance of the director of the Vesuvius Volcano Observatory, Prof. Raffaele V. Matteucci, and ended up becoming an unpaid assistant to the director. In early 1906, Perret thought he could hear a continuous buzzing coming through the floor of the observatory while he slept, and he eventually set up microphones to better hear the buzzing as a predictor of major eruptions.

The major eruption of Vesuvius began in April of 1906, and Perret would spend the next 15 years observing the volcano, taking photographs, and making observations. He also traveled around the world to make observations of other volcanos, including Kilauea in the Hawaiian Islands, and persuaded Harvard geologists there to establish a permanent observatory.

Incredibly, Perret was almost never paid for his work, and relied on donations and the kindness of others to undertake his work. He eventually received somewhat regular funding from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, which also published his monographs on various eruptions.

In 1929, Mt. Pelée started another lengthy eruption cycle, and Perret traveled to Martinique to make firsthand observations. He had an observation shack built on a ridge overlooking the mountain that was between two valleys, expecting that the pyroclastic flows would pass by on either side. He was mostly correct, except for that remarkable story I share in the TikTok when a freak blast sent a flow directly towards his shack!

When I first heard of the story of Frank Perret’s brush with volcanic death, he seemed to me to be a stereotypical American thrill-seeker, reckless and not necessarily that concerned with the actual science of volcanos. Perusing his book and his achievements, however, has shown me a very different side of the volcanologist. He took extremely detailed observations of almost every aspect of volcanic activity (as we will see), and he was very involved in the communities in which he worked and concerned for their safety. World War I broke out while he was studying Vesuvius, and he became a volunteer worker for the Red Cross, aiding war-stricken Italian civilians. When he arrived on Martinique, he provided the best information he could to the citizens of the new city of St. Pierre about the risks the volcano presented, and he established a Volcanological Museum that served as a place of education as well as a memorial to the victims of St. Pierre; that museum has been renovated and still exists today.

Perret was internationally famous due to his work, and was beloved by those who he worked to help. He was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor of France and a Knight of the Italian Crown by Italy. He was also made an Honorary Citizen of the town of St. Pierre.

His monograph on the eruption of St. Pierre is a gorgeous discussion of all the observations he made while at the mountain, filled with photographs and detailed descriptions. Let’s take a look at some of them!

Our first image is of the summit of St. Pierre, showing the remains of the old dome of the mountain destroyed by eruptions and the new dome that arose to replace it. Perret made many observations on dome growth on Mt. Pelée.

Photos showing the proximity of the mountain to nearby habitations appear in the book as well, a reminder that these eruptions have a human toll associated with them.

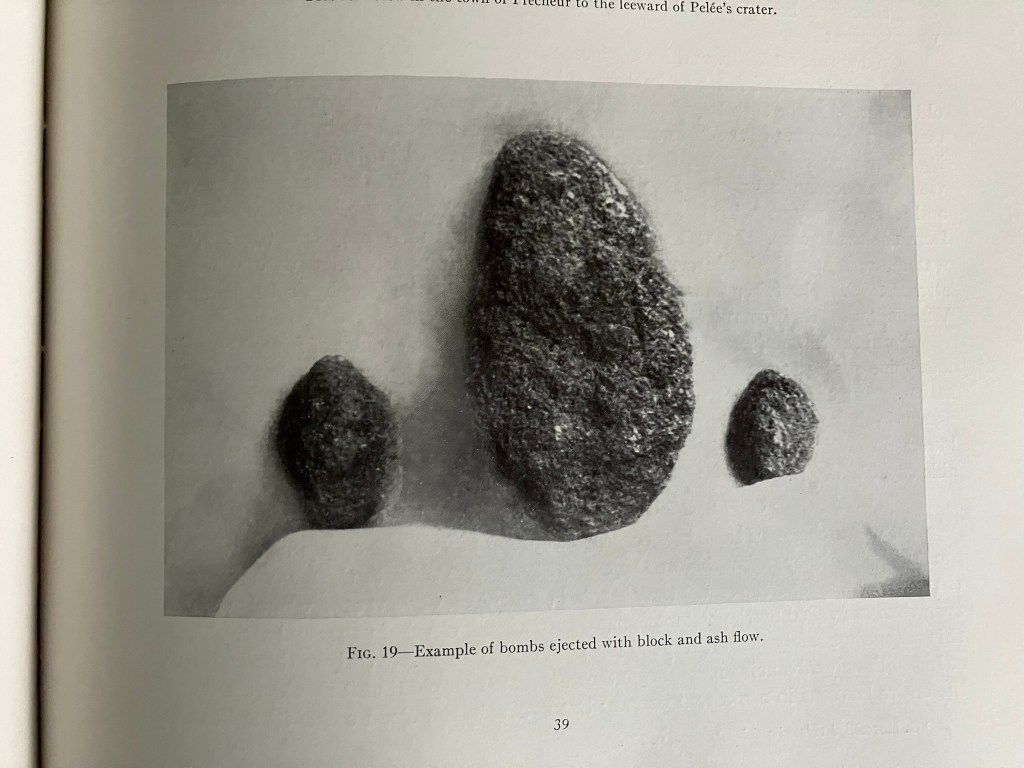

Mt. Pelée’s eruptions are explosive ones, and can toss “bombs” long distances. Perret includes photos of some of those bombs in his book.

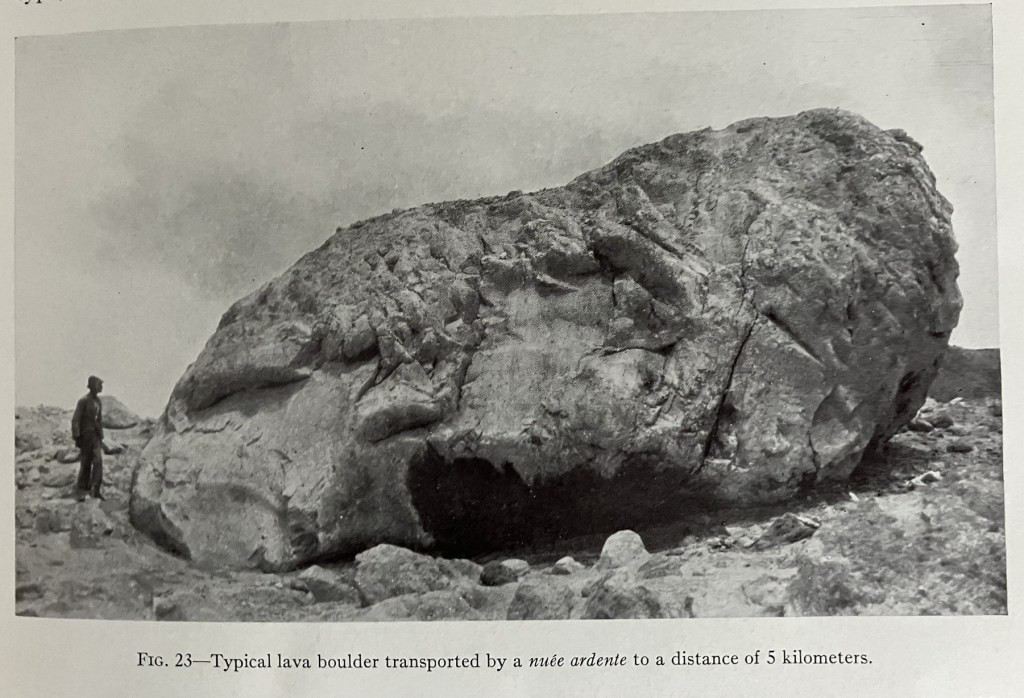

Some photos are absolutely terrifying but only if you know the context. The following image is of a massive boulder carried down the mountain by a pyroclastic flow (also known by its French name, Nuée ardente (glowing cloud).

Remember, this is a cloud of ash and gas that carried this boulder!

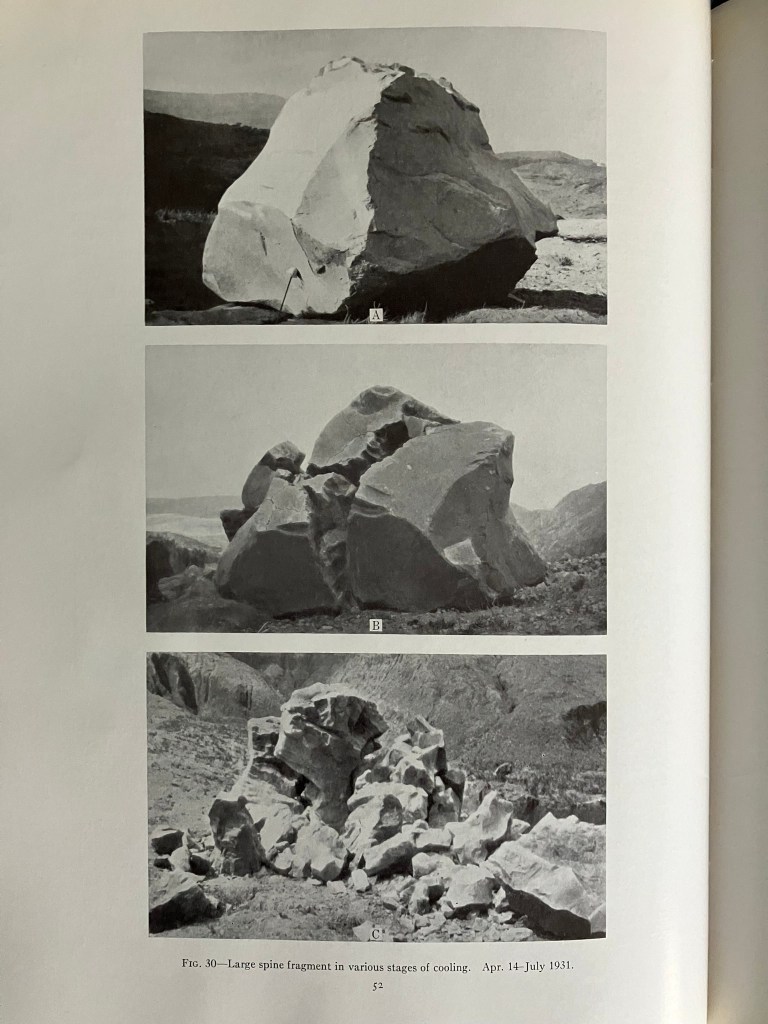

Perret was not only interested in the sensational parts of the volcano, but also considered other aspects of its eruption, like the crumbling of volcano debris as it cooled.

Perret also included photos of his observatory, which it should be remembered that he sheltered in from a pyroclastic flow and survived!

There is also an annotated photo showing the mountain and its proximity to St. Pierre and other points of interest.

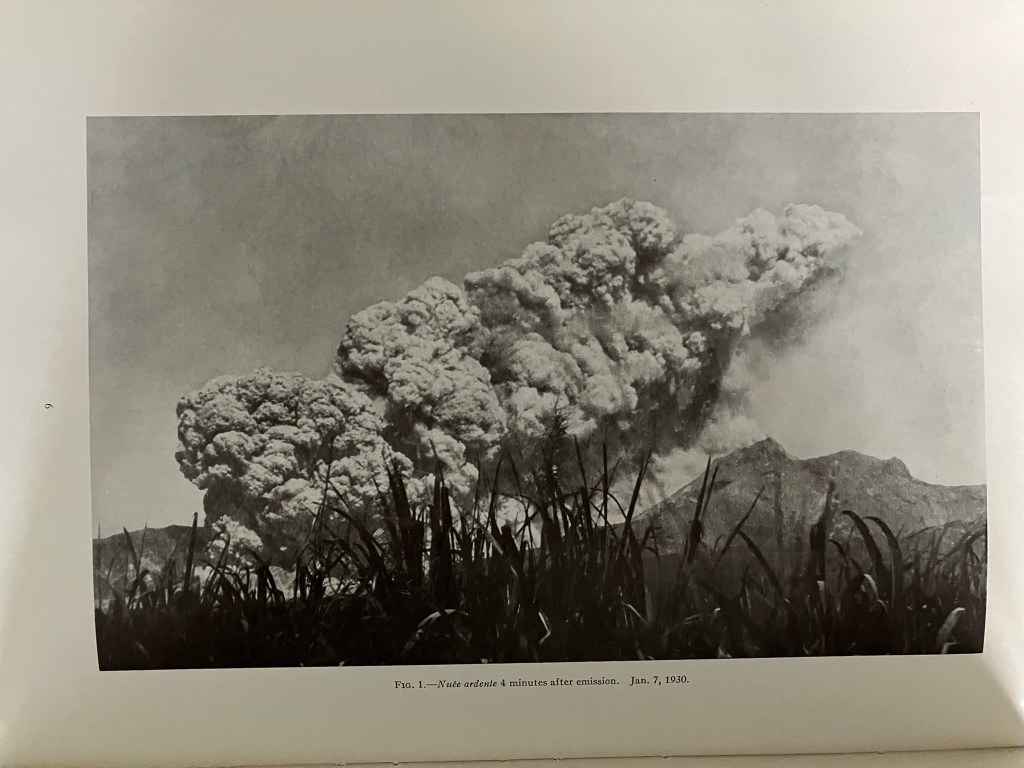

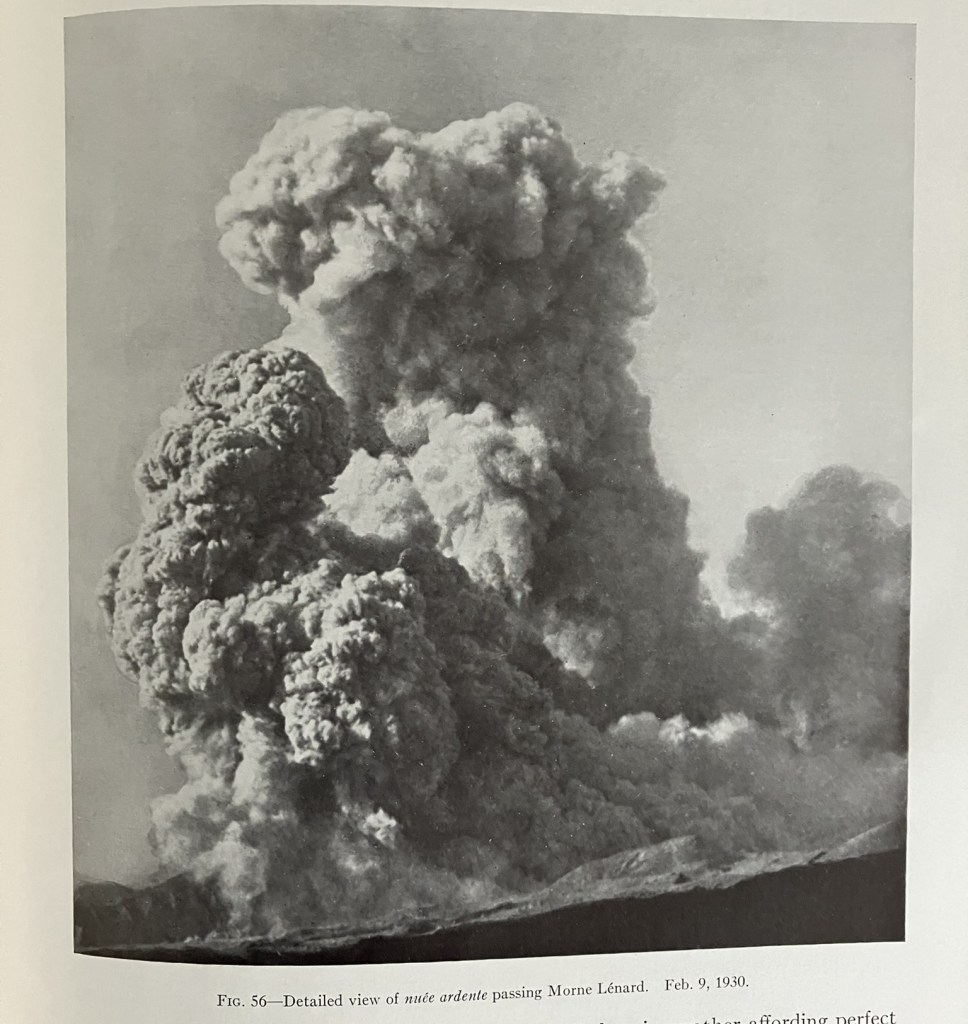

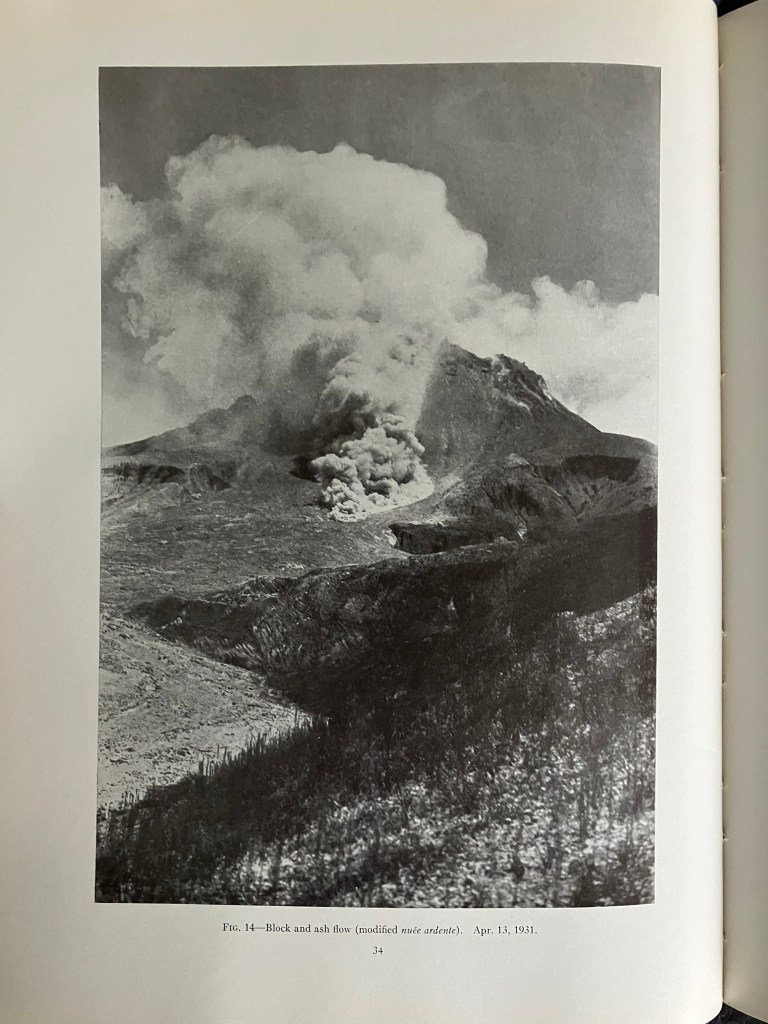

But the most amazing photos are of the pyroclastic flows themselves! Perret includes many beautiful and terrifying photos, a selection of which are posted below.

Perret also include time sequences, showing the evolution and expansion of the pyroclastic flows.

The final one I will show, below, is perhaps the most chilling. It appears to be a view from the beginning of a pyroclastic event, with the camera positioned seemingly right in its eventual path. This was not the one that Perret had a close encounter with, but it gives an idea of what he might have seen when he heard the eruption and first looked out his station door.

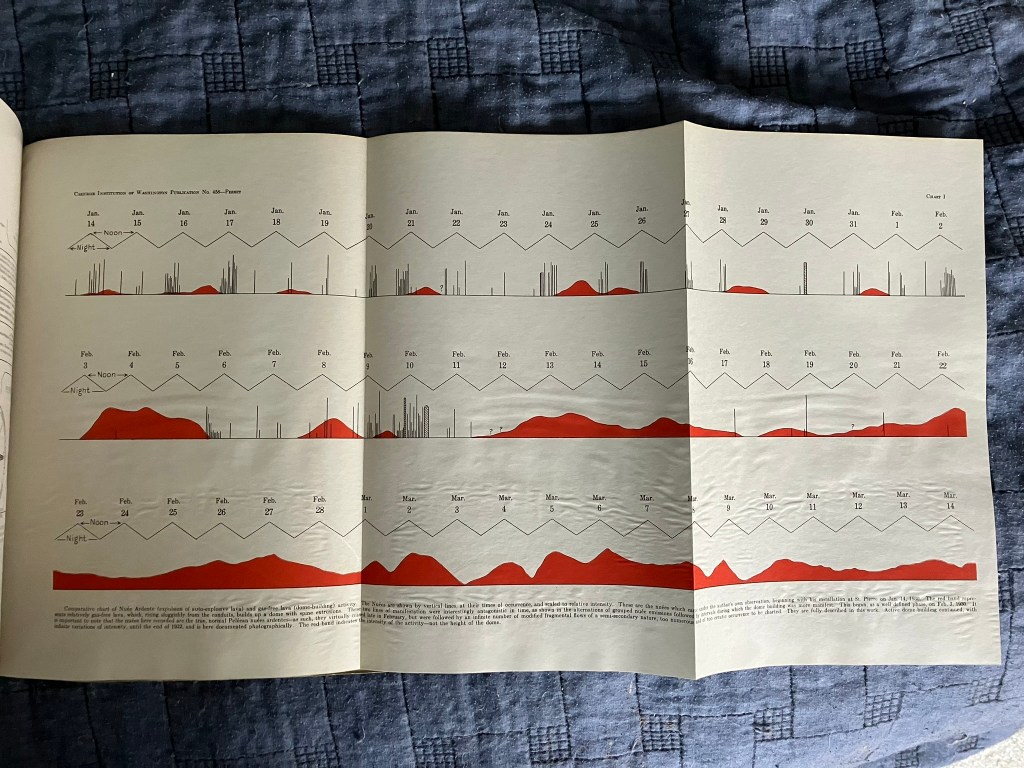

For a scientist, though, even the pyroclastic flow images aren’t the most spectacular part of Perret’s monograph. He also included a detailed figure showing the growth of the mountain in time and all the associated pyroclastic flows. This is a beautiful example of data presentation, and I love having an original copy of it!

And that should give you a pretty good idea of what sort of researcher Frank Perret was! He was deeply loved everywhere he went, as he himself once remarked1, presumably while in St. Pierre,

Wherever I go, even meeting people who do not know who I am, if I say I am Monsieur PERRET, it is wonderful to see how they show that they want to do everything possible.

*********************************

- Giblin, Mildred (1950-12-01). “Frank Alvord Perret (1867 – 1943)”. Bulletin Volcanologique. 10 (1): 191–196.