I’ve had a pretty long career in physics, optics in particular, at this point: I have published over 150 peer-reviewed papers and have written 5 books. Looking back to the start of my journey in science, I don’t think I could’ve imagined how much I would do. With that in mind, I was recently thinking back to my very first paper — published in 1997, almost thirty years ago — and I thought it would be fun to talk about the paper and its influence on my career.

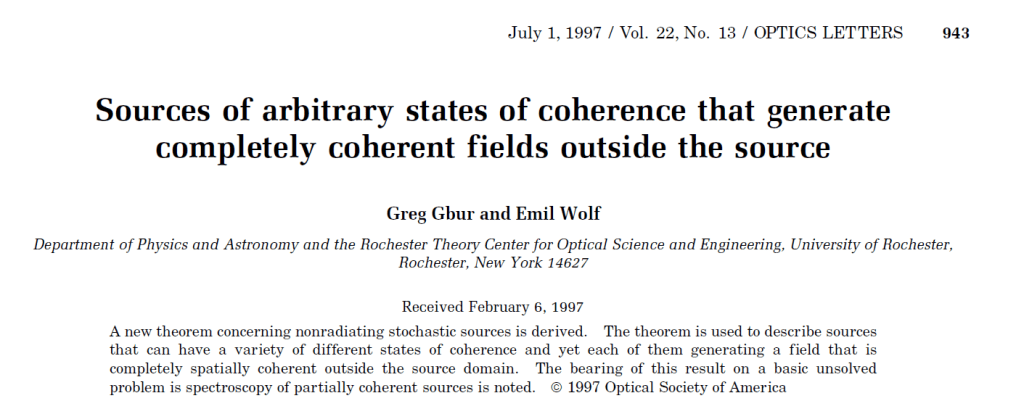

So here is the title and abstract of the paper:

The “Emil Wolf” in this case was my PhD advisor, one of the most distinguished optical scientists of the modern era. His book Principles of Optics, co-authored with Max Born and commonly just known as Born and Wolf, is one of the most cited scientific texts out there, with some 81,000 citations according to Google Scholar.

It’s worth noting how I ended up working for such a distinguished scientist in the first place. In 1996, I had been a graduate student in physics for two years and had been working in experimental particle physics. However, for reasons that I’ve blogged about before, I decided that this was not the field I wanted to work in. In short, though I liked the goals of particle physics, I didn’t really enjoy the day-to-day activities of the job, which is just as important for having a successful career. So one day I was lamenting this to my classmate and friend Scott Carney at a local Taco Bell, and he suggested I reach out to his advisor Emil Wolf, who was always looking for new students.

To some extent, I was lucky by virtue of timing: at that time, Emil was 74 years old and due to his age was having a harder time convincing students to work with him. I therefore wasn’t in competition with anyone else to be his student; in an earlier era, I might not have made the cut! Emil even acknowledged his age when I went to talk with him; he said something like “You should know that I’m old and could die at any time; however, my doctors say I’m in good shape and I’m still getting a lot of work done.” He then handed me a huge stack of his publications, all of which had come out in the past five years, and I was convinced.

I also realized that I had really always wanted to be a theoretical physicist, but hadn’t had the confidence to try it. Emil was the ideal advisor: hugely supportive and he and his wife Marlies treated all of his students like family.

For my first research project, Emil tasked me with proving a theorem involving so-called nonradiating sources. I’ve blogged about such sources before: a “nonradiating source” is a source of radiation that, paradoxically, doesn’t actually produce any radiation. They represent a primitive form of invisible object, in the sense that they cannot be detected even though they should be. (In fact, there is a direct connection between nonradiating sources and more familiar forms of invisibility, but that’s a topic for another post.)

The reason that nonradiating sources are so surprising in optics is that one of the consequences of Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetism is that oscillating, accelerating electric charges produce electromagnetic waves. It was then taken for granted for a number of years that any oscillating charge distribution will produce radiation; nonradiating sources demonstrate that this is not true.

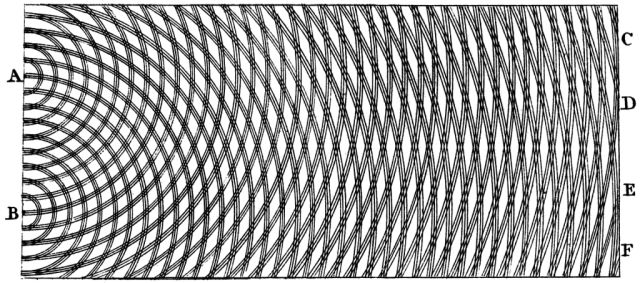

The physics of nonradiating sources is a direct consequence of wave interference. When multiple waves interfere, they can produce regions of destructive interference where there is no wave amplitude at all; the original and most famous demonstration of this is Young’s interference experiment where waves from two pinholes interfere with each other; here is how Young drew it in the early 1800s.

It turns out that when you have a three-dimensional radiation source, like a spherical volume filled with oscillating charges, there are cases where the combination of all the waves throughout the source can produce total destructive interference of all waves outside the source region. The source has all of its electromagnetic fields confined to its own volume, and none escape: it is a “nonradiating source.”

Here we move towards the topic of my first scientific paper. Beyond Born & Wolf, what Emil Wolf is most famous for is laying the foundations of what is known as optical coherence theory. You may have noticed that you don’t normally see light wave interference in your day-to-day life; the reason for that is that interference effects get “smeared out” by the random fluctuations of light coming from natural light sources. (One way to visualize this is to imagine Young’s interference pattern jittering randomly from side to side a million times per second: your eye cannot follow that rapid jitter, so you see the average pattern of light, in which all the highs and lows of the traditional pattern have been washed out.) A laser is a coherent source of light, and is the exception in terms of light sources. One can do Young’s experiment quite easily with a laser, but with a natural source of light like a lightbulb, one has to collimate the light beam and spectrally filter it in order to see the interference effects. That collimation and filtering makes the surviving part of the light beam more coherent.

This is important for the existence of nonradiating sources as well, which rely on destructive interference to cancel out the radiation. If the source becomes partially coherent, i.e. more random than a laser, then one expects in general that the nonradiating effect will be weakened or destroyed, and some radiation will be emitted.

Emil had a long history of studying nonradiating sources, and of course optical coherence, and he had already studied the possibility of making partially coherent nonradiating sources. It turns out that it can be done, but at the time one expected that a source had to be very coherent in order to achieve the nonradiating effect.

For students just starting out in research, Emil always gave them a non-trivial but straightforward problem to begin with, usually a problem that he already knew the answer to! The reasoning for this was to give the student a problem that definitely had a solution and that would result in a paper relatively quickly, to encourage them in their research endeavors. (I follow the same approach with my own students to this day.) In my case, Emil had thought up an interesting theorem relating to partially coherent nonradiating sources and wanted me to prove it, after which we could spin it into a paper.

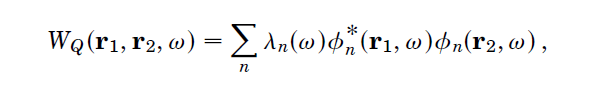

Now I will show you just a little bit of math to try to explain the idea! In coherence theory, waves are characterized by a so-called correlation function, in this case written as W, which represents the correlations of waves between two points in space, labeled r1 and r2. In 1982, Emil had published what would turn out to be a hugely important result in optical coherence theory, showing that every correlation function could be written in the mathematical form,

This became known as the “coherent mode representation,” and the functions labeled became known as “coherent modes.” The idea is that the

act like fully coherent waves, of the type that produce perfect interference patterns in Young’s experiments, and that any partially coherent field can be written as a sum (the symbol

represents a summation) of a set of coherent modes. Emil’s coherent mode representation makes a lot of difficult calculations in optical coherence theory a lot easier to do and can illuminate a lot of the physics of partially coherent sources and fields.

Emil’s task to me: assuming that the source W is a nonradiating source, determine what that implies about the coherent modes. Like I said, Emil already knew the answer, and he just wanted me to figure it out on my own, which I did. In order for the source W to be nonradiating, each of the coherent modes must itself be a nonradiating source. It was a simple and straightforward result, and probably only took me a day to figure out the math of it, even though I was completely new to optics at that point.

But then I ended up surprising Emil: I realized that there was a fascinating implication of this result that he hadn’t seen. It turns out that, in general, the degree of coherence — how coherent a source is — is inversely related to the total number of terms in the source’s coherent mode representation. That is, as we add more terms to the coherent mode representation, we make the source less coherent. I recognized that it was possible to make a very, very large set of nonradiating coherent modes; this meant that it was possible to make a very low coherence source that is nonradiating.

But it also led to another interesting implication: if our coherent mode representation includes one radiating mode and a large number of nonradiating modes, then the source will be quite incoherent but the radiated field will be fully coherent. This was quite surprising and unexpected, and Emil was very happy about this result. It led to the title of the paper, “Sources of arbitrary states of coherence that generate completely coherent fields outside the source.”

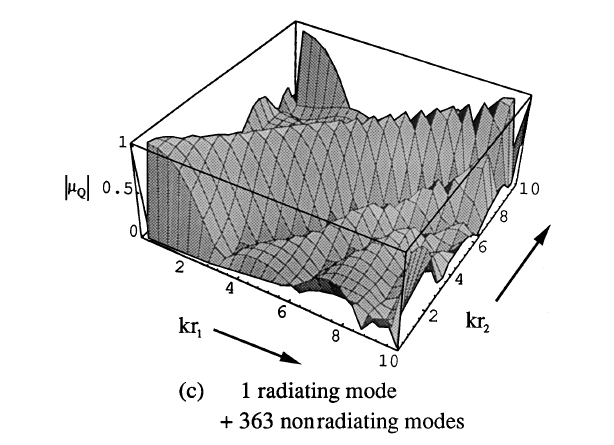

I did some simulations showing what the correlation function of one of these sources would look like; below is an example where the source has one radiating mode and 363 nonradiating modes. Why specifically 363 modes? With the low power Mac I was working on in 1997, 363 was the most modes I could get away with without the simulation just crashing.

That narrow ridge running across the middle of the plot indicates that the source only possesses correlations when the two points r1 and r2 are very close to each other, which is the characteristic of a very incoherent source. There is a limit to how incoherent a source can be and still be nonradiating, which I would come back to a few years later to demonstrate.

Emil had me write the first draft of the paper, which I think was maybe ten pages long. He took that draft, basically threw it out entirely, and rewrote it into a concise three-page paper! (He wanted me to get the experience in writing a draft myself so that I could then see why the changes he made were helpful.) It is perhaps worth noting that this was still the pre-internet era, where you submitted papers to a scientific journal by mail. There were no electronic submission systems yet, so you sent three copies of your paper to a journal which then sent them along to reviewers.

Emil added one final bit of insight to the paper draft relating to the spectra of sources. Emil’s work in the 80s had revolved around the idea of correlation-induced spectral changes, i.e. that the correlations of a source can strongly influence the spectrum of the field that is radiated. For our paper, Emil noted that the incoherent source-coherent field possibility indicates that it is virtually impossible to guess what the source spectrum looks like by measuring what the field spectrum is.

This paper was a milestone for me in many ways. Beyond just showing that I could do research to publish a paper, it showed me that I could come up with my own really neat ideas in research. This gave me a much-needed boost of confidence going forward that would carry me through my PhD and beyond.

This paper also sparked my lifelong interest in nonradiating sources and invisibility physics in general. My PhD was centered on nonradiating sources, and Emil asked me to write a review article on the subject, “Nonradiating sources and other ‘invisible’ objects,” that was published in 2003 before the “invisibility cloak” craze that started in 2006. In that review article, I delved deeply into the history of invisibility in physics, going back a century, and even included a quote from the first science fiction story on invisibility. This interest in the physics, the history, and the fiction of invisibility would eventually turn into my 2023 popular science book, Invisibility: The History and Science of How Not to be Seen.

My early investigations of the history of invisibility, spurred on by Emil’s interest and enthusiasm for the history of science, sparked my own love of history, which I still study and discuss to this day. (Including, I guess, this post.)

When I was first doing my PhD work, I started to worry about whether I would be employable doing work on a topic as esoteric as invisibility. However, I think Emil understood better than I did that this was a topic that would get people’s attention; also, for a time I became the world’s undisputed expert on the subject by default, just because nobody else was studying it!

It’s interesting to look back and think about how one single scientific paper really directed the entire course of my career. Of course, I also have to give credit to my friend Scott, who pointed me towards Emil in that fateful lunch in Taco Bell.

****************************************

Postscript added after publication: I hadn’t looked in a while and was curious how well cited my first paper is: it turns out it only has 11 citations! (For comparison, I now have something like 15 publications with over 100 citations.) Though it didn’t have a huge impact on the science of its day, it had a huge impact on my career path.