Working on the second edition of my Singular Optics textbook and thought I would blog about some of the fun developments in the field that I’ve come across while doing the book research!

Light has wave properties, and as a wave it can do wavy things like other types of waves — including swirling around a central point like a vortex. When a beam of light manifests one or more of these swirling regions, it is typically referred to as a “vortex beam” and the individual swirling structures are known as “optical vortices” (naturally). Beams possessing optical vortices turn out to be really useful in a lot of applications, and the field of study of such beams, and related “singular” beams, has become known as “singular optics.”

A vortex is a localized, conserved, and discrete structure in a wavefield and when we think of vortex beams, we usually think of beams possessing a finite number of vortices. An infinite number of anything is a concept alien to physics in general, as “infinity” is generally considered an unattainable idealized limit.

I’ve been obsessed with infinity in the context of optical vortices, however, and have published some really neat results on this subject (I will elaborate momentarily). Thus when I came across a 2021 paper by Kovalev and Kotlyar1 titled “Optical vortex beams with the infinite topological charge,” I was immediately intrigued! In this blog post I will give an overview of what optical vortices are, how they behave, and why it is fascinating that one can apparently cram an infinite number of vortices in a beam of light!

Our starting point is to discuss some basic features of waves, and then see how optical vortices naturally arise from this description; I will draw a lot from my old, more extensive, post on singular optics.

What do you imagine when you think of a wave? Many people, including physicists, probably imagine something like the following image.

This wavy line might represent a snapshot in time of waves on a string, if you were to repeatedly wave the left end end up and down. The ripples travel along the string to the right (hence the black arrow), maintaining their shape. The ripples repeat, and we can therefore characterize the current state of the wave at a particular position and time by an angle from 0 to 360 that we call the phase of the wave, as illustrated below.

This is a picture of a wave on a one-dimensional string. What do waves in three dimensions, like light waves, look like? To visualize them, we imagine only drawing the parts of the wave where it is at its maximum value, i.e. 0/360 degrees. These will tend to be surfaces in three dimensional space, and we call them the wavefronts of the wave. The simplest theoretical picture of such a wave is called a plane wave, because the wavefronts are parallel planes; the wave itself propagates, and carries energy, perpendicular to the planes.

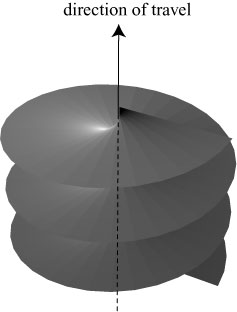

But it is also possible for wavefronts to be twisted together, like the levels of a parking deck! A simple example of this is shown below.

This represents a wave traveling upward, and the wavefronts effectively circulate around the central axis as time passes, like a spinning drill bit. This sort of structure is what we refer to as an optical vortex.

It is a bit impractical to study optical vortices by drawing three-dimensional pictures. When we detect light waves, we almost always measure the intensity (and indirectly the phase) by measuring it on a planar detector that measures the cross-sectional behavior of the beam. For the simplest optical vortex, the phase would then appear something like below.

In the cross section, the phase increases from 0 to 360, colored black to white, as one travels counterclockwise around the central point, which happens to be a zero of intensity. The phase is singular at that point, since we cannot define the phase if the wave amplitude/intensity is zero — if there is no wave waving, we can’t evaluate the phase!

We say these simple optical vortices are typical, or generic, features of wavefields, because any time we interfere three or more waves together, we expect optical vortices to appear. Here’s a simulated intensity and phase for four randomly-oriented plane waves:

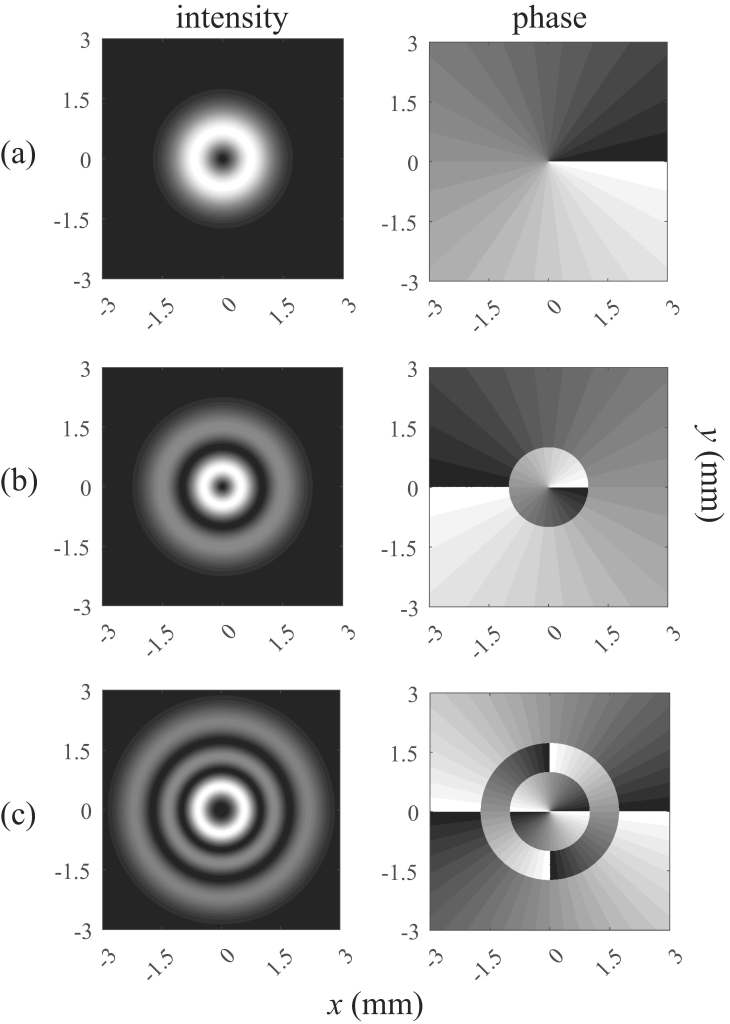

The singularities are easy to spot in the phase — they’re to locations where all shades of gray come together. One can see that for some of them, the phase increases by 360 when one makes a counterclockwise circle around them, and for others the phase decreases by 360. These are the typical vortices that can appear, but it is possible to make beams that possess central vortices where the phase twists more rapidly; one class of such beams are known as the Laguerre-Gauss beams, and the intensity and phase of a selection of them are shown below.

In the topmost one, the phase increases by 360 as one goes counterclockwise around the center; in the second, the phase decreases by 360 along a similar path. In the third, the phase increases by 720 degrees — it is a second-order vortex. It turns out that we can have a vortex of any integer order: +1, -1, +2, -2, +3, -3, and so on. The order represents the number of 360 degree changes the phase goes through as one circles the vortex, and every vortex has an integer order, which we also call the topological charge.

Why is it called a “charge”? It turns out that a vortex charge, like electrical charge, is a conserved quantity, and in general cannot spontaneously appear or disappear without annihilating with an equal and opposite charge. This property of stability — combined with the aforementioned discreteness of topological charge — make vortices attractive as information carriers in optical systems. A lot of work has been done, including by me, to study what happens to vortices when you propagate them long distances through the atmosphere.

Vortex beams have another property that makes them particular useful and interesting — because of the “twist” in the phase, they carry orbital angular momentum, and they can impart that angular momentum on objects they illuminate. This property has been used in optical micromanipulation to trap and rotate microscopic particles.

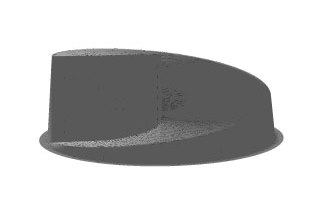

One natural question that follows from the aforementioned discussion: if topological charge is conserved, and appears in equal and opposite amounts, how can we get vortex beams, which have a net nonzero topological charge? This question was first asked2 by Professor Sir Michael Berry in 2004, and he looked theoretically at one of the original ways of generating a vortex beam: passing an ordinary Gaussian beam through a so-called spiral phase plate, as illustrated below.

Imagine that this ramp-like structure is made of transparent glass, and light shines through it from below. The light will be delayed passing through the glass, and this delay will cause the phase to twist around the center of the spiral. If the thickness if the spiral is chosen correctly, the phase will come out with a twist that is some multiple of 360 degrees — we will have created a vortex beam!

Berry asked: what happens if we don’t have a perfect phase plate, but one that effectively imparts a fractional twist on the phase between 0 and 360 degrees? The answer is that, at every half-integer value of the effective topological charge, i.e. 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, etc., an infinite number of singularities appear, stretching off into the darkness of the beam. A picture of what this looks like near the beam center is shown below.

An infinite number of plus-minus pairs are created, and as the fractional plate is increased beyond a half-integer, we get a remarkable Hilbert Hotel-style annihilation of charges, where each charge annihilates with it opposite neighbor, leaving one extra charge in its place! Berry didn’t comment on the relation to Hilbert’s Hotel back in 2004, so in 2016 I wrote a paper highlighting this remarkable connection3.

The violation of topological charge conservation is allowed to occur because, once an infinite number of pairs are present, the topological charge is undefined, just as the following sum is undefined.

Depending on how we sum this infinite series, we can make it take on any value we want! For example, if we put parenthesis around the first pair and every pair that follows, we have

.

But if we start the parenthesis at the second term, we have

.

The conservation of topological charge can be violated because topological charge cannot be evaluated when there are an infinite number of plus-minus charges in the field!

This Hilbert’s Hotel mechanism has been demonstrated experimentally several times, including by a collaboration I was a part of4.

So it is possible to have an infinite number of positive and negative charges appear in a beam to make the total undefined, but can one actually make the topological charge itself infinite? Surprisingly, the answer appears to be “yes!” Kovalev and Kotlyar drew inspiration from a paper by Abramochkin and Volostnikov that was first published way back in 19935. In that earlier paper, the authors showed method to theoretically impart a finite number of vortices on a beam that would remain shape invariant on propagation, i.e. as the beam travels, it will retain its shape and its vortices.

Kovalev and Kotlyar noticed that there is no reason why that Abramochkin and Volostnikov method can’t be used to construct a beam with an infinite number of vortices, with an infinite topological charge!

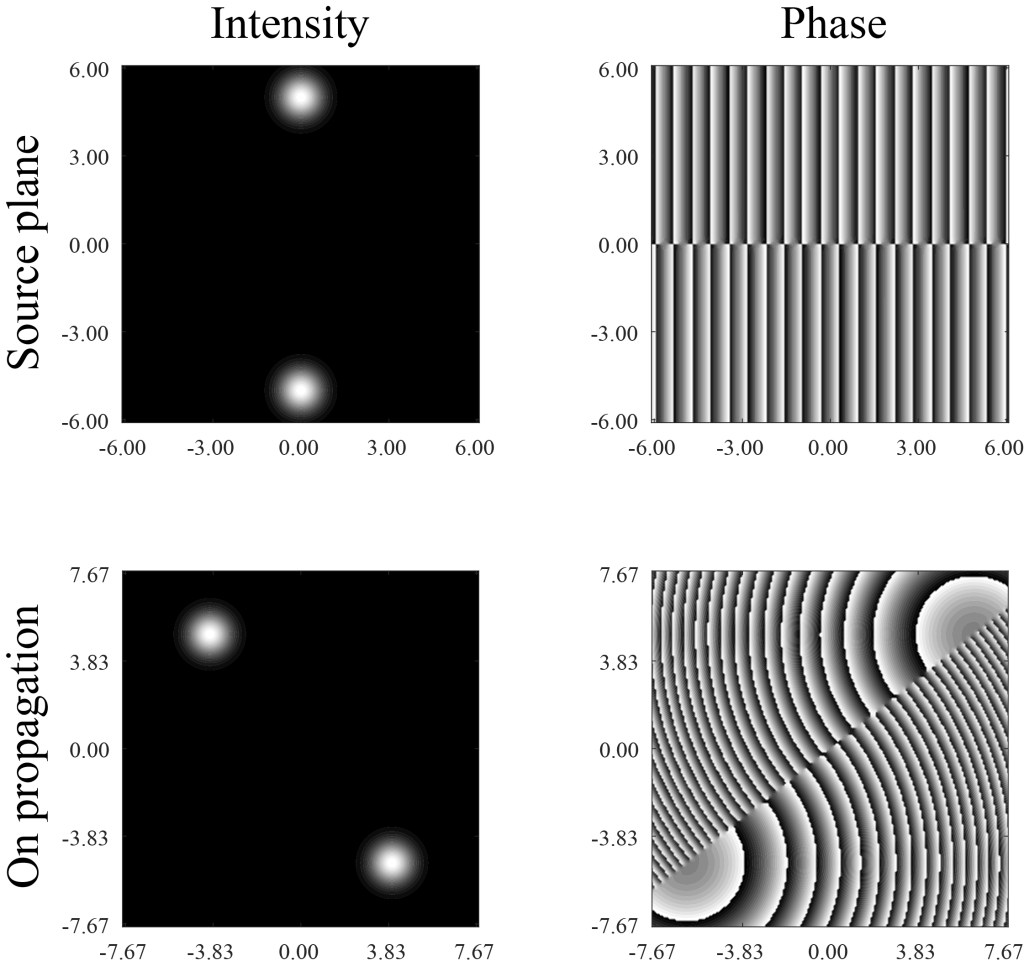

I won’t go into all the math here — this post is complicated enough already! — but we can show some examples. Below is a simulation of a beam with an infinite number of positive vortices, shown both in the source plane and after propagation for 50 meters. The line of vortices basically splits the beam into two bright spots, with the line running between them.

Obviously, we can’t see all the singularities, which stretch off in a line towards infinity, and are effectively lost in the darkness at the beam’s edge. On propagation, the entire beam rotates, eventually rotating a full 90 degrees as it approaches infinity.

What happens to the orbital angular momentum of the beam? Though there is an infinite topological charge, and in principle infinite phase circulation, most of it happens far away in the low intensity rim of the beam, and Kovalev and Kotlyar were able to show that the total orbital angular momentum is consequently finite.

An in principle infinite number of zeros in a beam is not completely unprecedented, because researchers have long known about so-called nondiffracting, or Bessel, beams, which have a Bessel function transverse profile. The intensity of such a beam is a series of rings of decreasing brightness with zero rings between them.

Those zero rings, however, do not possess a topological charge, and so are not as seemingly paradoxical as the infinite topological charge beams described here.

One question that isn’t completely answered by Kovalev and Kotlyar is a method for constructing a beam with infinite topological charge. They note that a beam with an infinite number of zero lines — like a Bessel beam, but vertical instead of circles — can be converted with lenses into an infinite topological charge beam, but that beam with an infinite number of zero lines itself can only be approximately constructed by ordinary means. It is to be an interesting open question as to whether some sort of simple beam, like a Laguerre-Gauss beam, can be converted optically into one of these unusual vortex beams. (Though I think I just figured out how to do it.)

Overall, the paper by Kovalev and Kotlyar again demonstrates that the concept of infinity can play a role in physics problems in truly surprising and enlightening ways!

***************************************************

- A.A. Kovalev and V.V. Kotlyar, “Optical vortex beams with the infinite topological charge,” J. Opt. 23 (2021), 055601.

- M.V. Berry, “Optical vortices evolving from helicoidal integer and fractional phase steps,” J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 6 (2004), 259.

- G. Gbur, “Fractional vortex Hilbert’s Hotel,” Optica 3 (2016), 222-225.

- E. Abramochkin, V. Volostnikov, “Spiral-type beams,” Opt. Commun. 102 (1993), 336-350.

Hi, Gregory:

I just wanted to make sure you were aware that seven of your books are covered by the Bartz v. Anthropic Settlement (see attached screenshot). Apparently, they’re paying $1,500 per book, so worth looking into.

Here’s the lookup page so you can see the titles that are covered: https://secure.anthropiccopyrightsettlement.com/lookup

Here’s the Author’s Guild page with details about filing:

https://authorsguild.org/advocacy/artificial-intelligence/what-authors-need-to-know-about-the-anthropic-settlement/

Brad

Thanks! I need to look into it.

Great. I used to take care of a blog for my late friend, Larry Keene. This is actually Bradley Steffens, author of Ibn al-Haytham First Scientists. Oddly, none of my 75 nonfiction books are covered by the settlement.

Does this survive a reflection? I am wondering if it could be used to prevent jamming in a radar signal.