The fields of optical science and engineering have undergone dramatic changes over the past twenty years. Through most of its history, stretching back for hundreds of years, optics researchers have been asking the question, “what can light do?” Revolutionary discoveries have changed the question to, “how can we make light do whatever we want it to?”

One area where there has been dramatic change in recent years is in the very structure of a beam of light itself. Ever since the invention of the laser, it has been the standard source of light for experiments an applications, far superior to using natural light sources, which must be collimated and filtered to produce a directional and monochromatic beam. Most ordinary laser sources, like a laser pointer you might use to entertain your cats or give a presentation, produce a Gaussian beam, so named because they produce a brightness (intensity) spot shaped like a Gaussian function, as shown below.

A Gaussian beam is great for most uses: it is very directional, and propagates long distances without significant spreading, it is very close to being a single frequency wave, which also means it is coherent (more on this momentarily). However, researchers have gradually realized that beams with properties different than a Gaussian beam could show unusual, beneficial, and even seemingly impossible behaviors! These beams are created by modifying, or “structuring,” the properties of the beam spot.

There are a number of properties that can be structured in the transverse cross-section of the beam. The shape of the intensity spot can be changed, the phase of the light wave can be modified, the polarization properties of the light can be manipulated, and the spatial coherence can be adjusted. Let’s look at examples of each of these “structured” light beams, and see what weird things can be done!

Before we begin, let’s say a few words about waves. We’ll talk exclusively about single-frequency (i.e. monochromatic) waves, which act like perfect trigonometric sine waves. If we’re talking about one-dimensional waves, like waves on a string, we would have a picture something like this:

The height of the wave is called its amplitude; the intensity, or brightness, of the wave is mathematically related to the square of the amplitude. The wave moves up and down in a repeating motion; the phase is a number that represents the point of this up and down motion the wave is currently at. It is often simplest to describe a wave, especially when looking at waves traveling in three-dimensional space, by only drawing the “up” parts of the wave; these are referred to as the wavefronts.

In three-dimensional space, at a single instant of time, a wave has an amplitude and phase at every point in space. The wavefronts end up being surfaces in three-dimensional space — but we’ll get to that.

One of the oldest known forms of structured light involves changing the amplitude of a beam. Most light waves, including Gaussian beams, spread as they propagate. I remember one of the first times I got a laser pointer, when I was in graduate school: I shined it down the block against the side of a house. Though the laser beam makes a very narrow spot close to the source, it was a spot several feet in diameter after traveling down the block. This phenomenon, of light spreading as it moves away from the source, is known as diffraction.

In 1987, however, a researcher named Durnin demonstrated theoretically, that a beam that has an amplitude profile in the shape of a Bessel function will be effectively nondiffracting. These results were confirmed experimentally by Durnin and colleagues soon afterwards1, and the beams in question became known as Bessel beams or nondiffracting beams. The intensity of a such a beam looks something like this in cross-section (again, as if you were looking right at the beam, which isn’t recommended):

Note the multiple rings, which are characteristic of a Bessel function. It turns out, however, that a theoretically perfect Bessel beam would have an infinite amount of energy, extended through all the rings out to infinity, so in practice a Bessel beam is truncated and is only nondiffracting over a finite propagation range. These beams have been studied for optical communications, for trapping of microscopic particles by light beams (known as optical tweezing), and more.

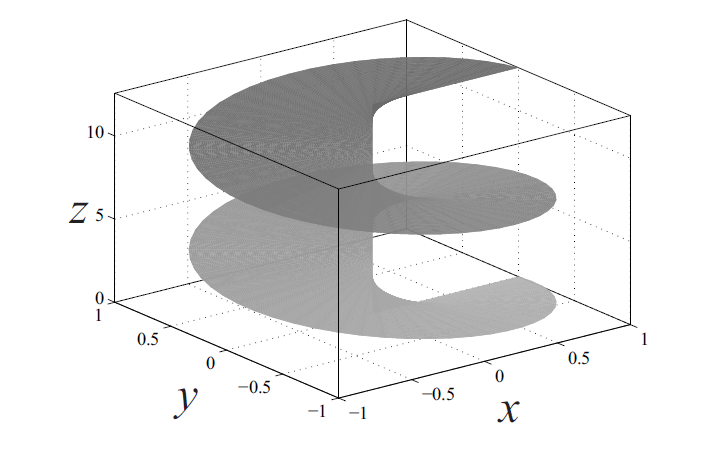

Nondiffracting beams are surprising enough, but closely related to them are so-called Airy beams, which have an amplitude distribution given mathematically by an Airy function2. When we think of ordinary light beams propagating in space, we imagine that light follows straight lines; the incredible thing about Airy beams is that they seem to “self-accelerate,” or follow a curved path as they propagate in empty space. The following picture shows a simulated snapshot of an Airy beam propagating in the z-direction. You can clearly see that it follows a curved path as it propagates along z!

I’ve talked about Airy beams before on this blog, a long time ago. People have suggested using Airy beams for peeking around corners, where ordinary light beams cannot reach. Both Airy beams and Bessel beams were surprising when they were discovered and announced because they challenge our intuition about what light beams should be able to do and not to do.

What about changing the phase of a light beam? Most light waves, including ordinary Gaussian beams, tend to have planar wavefronts that stack parallel to each other, like slices of bread in a loaf. But it was recognized in 1974 that it is also possible to create beams where the wavefronts are connected to each other and twisted together, like a screw or the levels of a parking deck, as illustrated below.

As this beam with a twisted phase structure travels, it spins with a definite clockwise or counterclockwise sense. Because the light wave has a handedness to it, it has been shown that it carries orbital angular momentum3, and can impart that angular momentum on small particles! Researchers have used these beams, which are also called orbital angular momentum beams (OAM beams) or vortex beams, to trap and rotate microscopic particles. OAM beams have also been considered as a way of increasing the information capacity of optical communication systems; it turns out that the vortex “twist” is a discrete quantity, and one can impose a twist of 1, 2, 3, 4, or higher integer value, and that vortex beams with different twists can be combined together and separated out. Each vortex beam can carry different information, which allows us to dramatically increase the amount of information carried through an optical fiber or through a free-space communications channel. This is a lot of the work I do, personally, for my own research. The study of vortices and other types of wavefield singularities is known as singular optics.

The most common vortex beams are modifications of a familiar Gaussian beam; however, it is also possible to impart a vortex structure on a Bessel beam; a lot of research on structured light has looked at how to combine different interesting structures to make novel beam types with previously unseen properties.

Light is a transverse electromagnetic wave, and that means that the light wave has electric and magnetic fields that oscillate perpendicularly to the direction the wave is traveling. This is roughly illustrated below, with “E” representing the electric field, and “H” representing the magnetic field.

The direction and manner in which the electric field oscillates is referred to as the polarization state of the light. For most of the history of optics, researchers concentrated on light waves that had the same state of polarization everywhere in their cross-section. For example, the electric field might oscillate horizontally at every point or might move in a circular pattern at every point.

But in 2000, researchers started looking at light waves where the state of polarization is different at different points4. The simplest examples are beams where the oscillations of polarization point radially outward from the center of the beam, and beams where the oscillations circle around the center of the beam; these are known as radially polarized beams and azimuthally polarized beams, respectively. Beams that have a nonuniform state of polarization are often referred to as vector beams.

Radially polarized beams in particular have been shown to have advantages over uniformly polarized beams; for example, radially polarized beams can focus to a smaller spot of light, improving the resolution of imaging systems5. In my own work, I have shown that certain types of vector beams are more resistant to being distorted by atmospheric turbulence6.

The final type of structuring one can do to a light beam is manipulate its state of coherence. So far we have considered light beams that, ideally, are perfectly monochromatic (single frequency). But all realistic light sources possess some random fluctuations in space and time, and these fluctuations change the way in which the generated light beam travels through space and interacts with matter.

It would take a bit more explaining than I’m ready to do here to discuss partially coherent light beams, but let me give a few general remarks. The early days of research in optical coherence theory involved characterizing the natural fluctuations of light; in more recent years, researchers have realized that there are many new effects that can be created by introducing a controlled randomness to a light beam! There has been a large body of research (which I have been involved in) showing that partially coherent light beams are less affected by atmospheric turbulence, making them ideal for any applications where you want to send light through the air over long distances7. People have also shown other unusual effects can be created with coherence manipulation, including beams that self-focus8.

All of these ways to structure light — amplitude, phase, polarization, and coherence — have been combined in various ways to make even more unusual beams! For example, people have made partially coherent vector vortex Bessel beams, and more! Structured light is a great example of the change in research focus that has happened in optics recently — we no longer ask “what can light beams do?” and now ask “how can we make light beams do whatever we want?”

*********************************

- Durnin, Micelli and Eberly, “Diffraction-free beams,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 58 (1987), 1499.

- Berry, Balázs and Nándor, “Nonspreading wave packets,” Am. J. Phys. 47 (1979), 264.

- Allen, Beijersbergen, Spreeuw, and Woerdman, “Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes,” Phys. Rev. A 45 (1992), 8185.

- Youngworth and Brown, “Focusing of high numerical aperture cylindrical vector beams,” Opt. Exp., 7 (2000), 77.

- Dorn, Quabis, and Leuchs, “Sharper focus for a radially polarized light beam,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 91 (2003) 233901.

- Gu, Korotkova, and Gbur, “Scintillation of nonuniformly polarized beams in atmospheric turbulence,” Opt. Lett. 34 (2009), 2261.

- Gbur, “Partially coherent beam propagation in atmospheric turbulence [Invited],” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 31 (2014), 2038.

- Ding, Koivurova, Turunen, and Pan, “Self-focusing of a partially coherent beam with circular coherence,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 34 (2017), 1441.