As long as I’ve been having fun tracking down classic science fiction stories that I absolutely love, let me share at least one more! “The Little Black Bag,” by C.M. Kornbluth, first appeared in the July 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. (You can read it on the Archive at this link.)

Cyril M. Kornbluth is one of my favorite science fiction authors, and largely due to three stories, that encapsulate a truly prescient view of the future and an extremely cynical one. In his story “The Silly Season” (1950), strange and nonsensical events worldwide that take up the attention of the newspapers turn out to be a distraction for an alien invasion. This story really anticipates the “noise chambers” that a lot of media companies have become, harping on nonsense issues to distract from serious ones. In his story “The Only Thing We Learn” (1949), a teacher recounts to students the heroic origins of their civilized society, whereas flashbacks show us the horror and brutality that those founders actually achieved. This story warns against the whitewashing of our history, while cynically suggesting that it will repeat itself with another conqueror.

The third story is “The Little Black Bag.” (Severe spoilers from here on out, so please read it first from the link.)

“The Little Black Bag” is a story of paradise lost, of humanity’s greed causing it to lose a truly unique opportunity for lasting prosperity and happiness. (As I said, Kornbluth was exceedingly cynical.) It is also a time-traveling story, and is set in two eras — the “present,” aka the 1950s, and the distant future sometime in or beyond the 25th century.

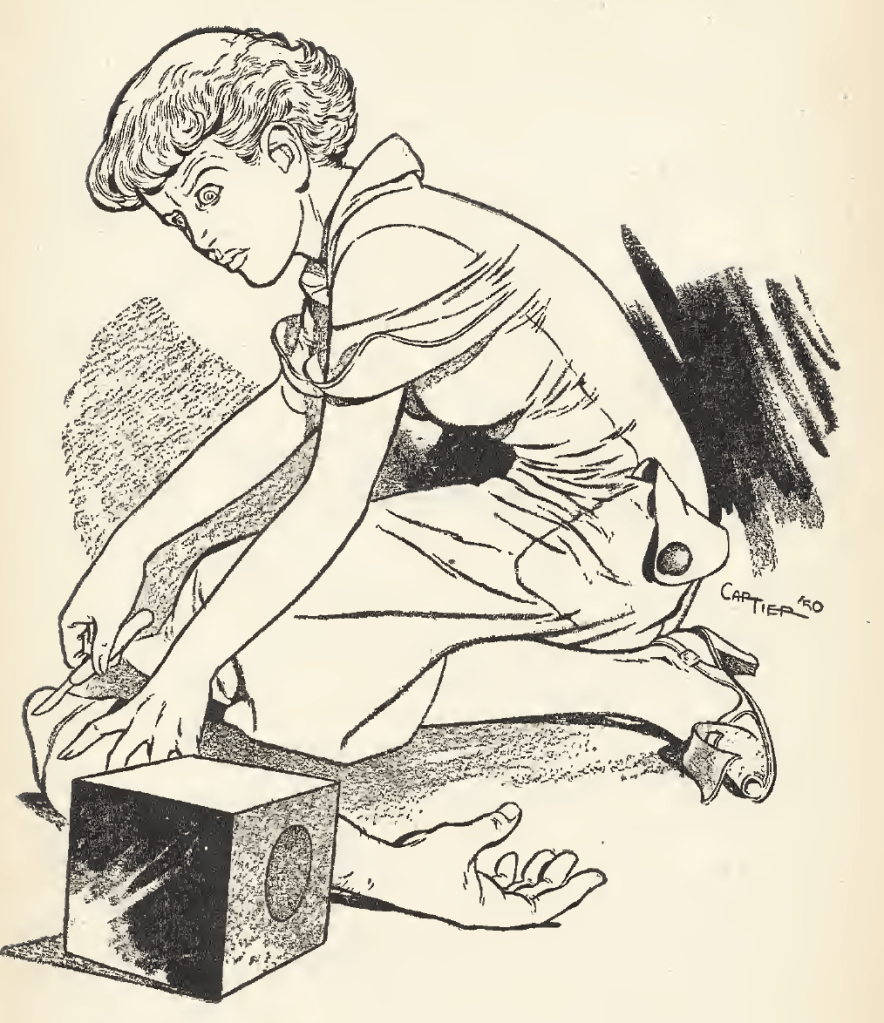

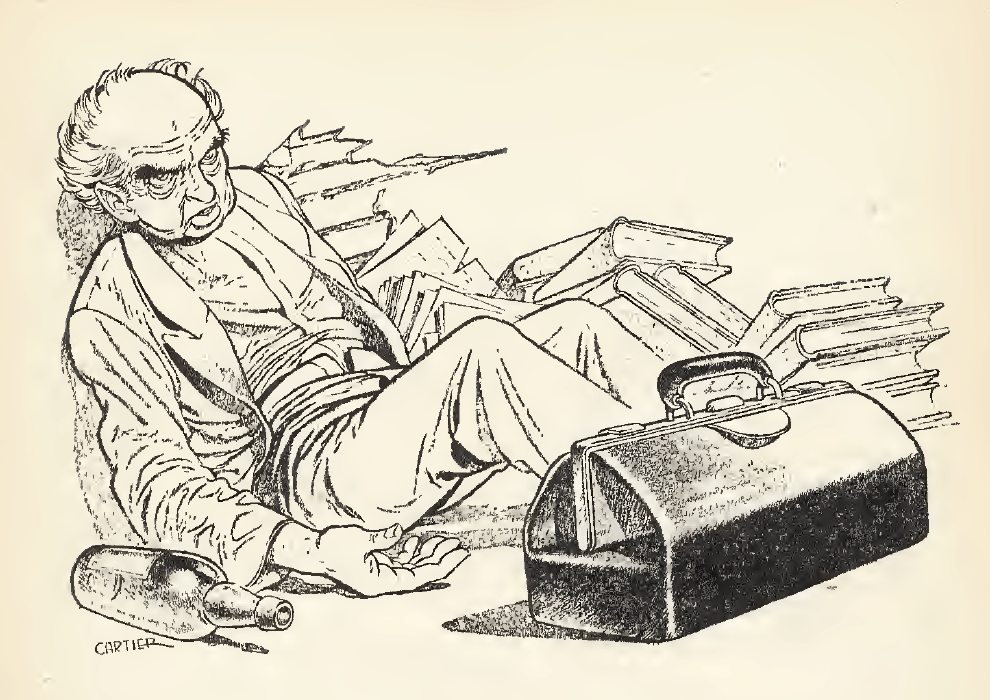

The story begins in the present, as we meet Dr. Bayard Kendrick Full. Once a prestigious medical doctor, Full was barred from medical practice for scamming patients, and now lives in a slum, drunk and destitute. Surprised by a neighborhood dog, he drops his latest bottle of booze, shattering part of it, and hardly notices or cares when a young girl passes by and curiously cuts her hand on one of the glass fragments.

Fast-forward to the 25th century, where humanity is in a bit of a pickle. As Kornbluth describes it, with what I consider a brilliant bit of wordsmithing,

After twenty generations of shillyshallying and “we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it”, genus homo had bred himself into an impasse. Dogged biometricians had pointed out with irrefutable logic that mental subnormals were outbreeding mental normals and supernormals, and that the process was occurring on an exponential curve. Every fact that could be mustered in the argument proved the biometricians’ case, and led inevitably to the conclusion that genus homo was going to wind up in a preposterous jam quite soon. If you think that had any effect on breeding practices, you do’ not know genus homo.

It is rather unscientific to ascribe intelligence to breeding like some sort of genetic trait; we don’t even properly know how to define intelligence. But I’ve always interpreted Kornbluth’s passage as describing a society where incurious people who are actively hostile to knowledge and learning and pass along that ignorance to their children. Then, in this age of rampant anti-scientific thought where flat earthers and anti-vaxxers are seemingly all over the place, Kornbluth’s future seems prophetic. Modern readers will probably immediately see a similarity to the 2005 movie Idiocracy.

In 2450, most people are profoundly stupid, and the few brilliant geniuses left over act more or less as behind the scenes handlers for the majority of the population. Even medical doctors are largely idiots, but are still able to do their job due to a super-technological “little black bag” that contains in its extradimensional interior cures for all ailments and instructions how to use them.

In the future, one idiot “physicist” named Walter Gillis taunts his handler, Mike, about making him a time travel machine, and Mike, in a fit of pique, obliges. Gillis in turn brings the portable machine home and shows it to his friend, John Hemingway, M.D. To demonstrate the machine, Gillis puts Hemingway’s little black bag in the machine — and it vanishes. Neither of them thought about how one might get it back.

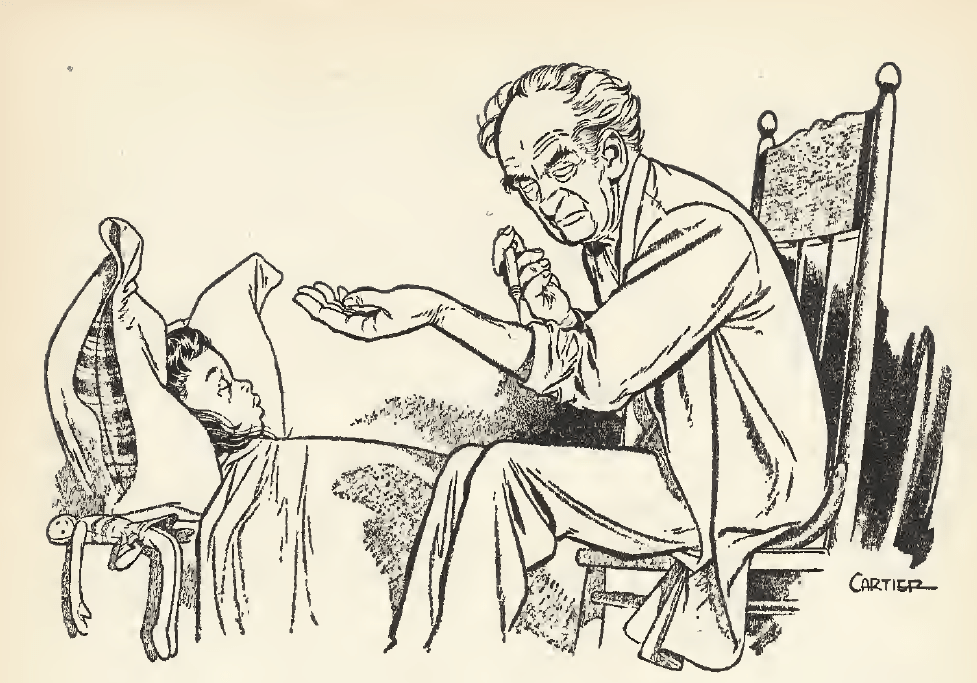

In the present, after a rough night of drinking, Dr. Full wakes up to find a mysterious little black bag sitting in the middle of his room. He opens it and finds scalpels and syringes and devices that he has never seen before, and can hardly understand.

His first reaction is to sell it for a few bucks for booze.

On the way out, however, the mother of the little girl who cut her hand begs for his help. The girl has developed a serious infection, and her mother is willing to pay Dr. Full two dollars for his medical assistance. Full obliges, though he assumes that there is little he can actually do, but when he follows the directions in the bag, he finds a syringe that in fact heals the girl completely and almost instantly. (He has no scruples at this point, but he isn’t an idiot — he first tests the syringe on himself.)

Full’s success comes to the attention of a young woman, named Angie, who knows that Full is a quack and demands a cut of the proceeds from the sale of the bag. They are unable to find anyone to buy it, however, because nobody knows what it is — and, in fact, they soon find that the patent for the medical bag was filed in the year 2450.

We flash forward some time to find that Dr. Full has opened a successful clinic in his neighborhood, with Angie as his assistant, and they are doing a magnificent job treating and caring for the people of the community. But Dr. Full wants to do more — he realizes that the little black bag could be a gift to all of humanity, and he wants to donate it for study to the College of Surgeons. Angie, on the other hand, wants to use it to get rich by doing plastic surgery on rich old ladies.

They argue, there is a scuffle, the bag opens, and — Angie fatally stabs Dr. Full with one of the scalpels in the bag. Most of the medical scalpels are designed so that they will cut only the tissue specified, allowing bloodless, incisionless surgery. But Angie uses the scalpel designed for amputations. Once her shock is gone, she quickly opts to hide the evidence of her crime. The little black bag also comes with a waste disposal box, so she slowly cuts up the body of Dr. Full and deposits it, piece by piece, in the box. (All the incisions are bloodless, so it is not as messy as one might imagine.)

Soon Angie has set herself up as a plastic surgeon, but her very first patient catches a glimpse of all the surgical tools in the box, and refuses to be operated on. Angie happily offers to use the safe scalpels on herself first, to show they’re safe…

… in the future, a monitoring system set up to track the usage of the little black bags shows that Dr. Hemingway’s has been used in a murder, and it is promptly switched off…

A little aside here; I first learned of Kornbluth’s work in the sixth series of Isaac Asimov Presents The Golden Years of Science Fiction. Asimov recalls of Kornbluth,

In reading Cyril’s stories, it is impossible to miss the fact that he tends to despise people generally.

I suppose I can’t blame him. I can’t place myself into his mind, but he was so much brighter than anyone he encountered that he must have worn himself out trying to stoop to the level of others.

Personally, from reading his stories my impression is that he was just profoundly disappointed in humanity. He could see a lot of our flaws that we ourselves couldn’t, and it angered him. And that anger sometimes turned into the most poetically horrific fates for the worst of his characters. Angie was one of those characters. Let me share the fate in full; one of my favorite lines in all of literature is the sentence with “hardened morgue attendants.”

Angie smiled with serene confidence a smile that was to shock hardened morgue attendants. She set the Cutaneous Series knife to 3 centimeters before drawing it across her neck. Smiling, knowing the blade would cut only the dead horny tissue of the epidermis and the live tissue of the dermis, mysteriously push aside all major and minor blood vessels and muscular tissue— Smiling, the knife plunging in and its microtome-sharp metal shearing through major and minor blood vessels and muscular tissue and pharynx, Angie cut her throat.

By the time the police arrive, the contents of the bag have decayed and rotted to uselessness.

This is just one of my all-time favorite stories. It even includes a bit of a reference to the mathematics of infinity, in describing how the medical bags never seem to run out of supplies:

As he understood it, and not very well at that, the stuff wasn’t “used up.” A temporalist had tried to explain it to him with little success that the prototypes in the transmitter had been transducted through a series of point-events of transfinite cardinality. A1 had innocently asked whether that meant prototypes had been stretched, so to speak, through all time, and the temporalist had thought he was joking and left in a huff.

“Transfinite cardinality” is the mathematicians’ way of referring to sets of “things” where the number of “things” is infinite; if you’re curious, I’ve written a series of blog posts about the math of infinity. I just love seeing these concepts pop up in science fiction.

In “The Little Black Bag,” Kornbluth describes a future where the supernormals of society are struggling to figure out what to do about the population of subnormals around them. Kornbluth himself would answer this question in a sequel called “The Marching Morons,” which appeared in 1951. I will discuss this story in a future post, but it turns out that the supernormals are far too morally evolved to come up with a ruthless solution to their perceived problem; but when a cryogenically frozen person from the 20th century is thawed, he is amoral enough to present them with an idea. True to Kornbluth’s anger towards awful people, this does not go as well for the 20th century man as he had hoped.

“The Little Black Bag” has been adapted for television multiple times, most notably as an episode of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery series. It is a remarkable and remarkably well-written science fiction classic, and well worth reading.

Cool stuff!.

This is what I love in your post

Interesting and insightful analysis of Kornbluth’s “The Little Black Bag” and its prophetic view of a future society.

Thanks, Ely

Future society? I think we’re not very far from this…

I had forgotten about this story! So glad you mentioned it (I have that Asimov collection. . . somewhere around here). I think I even have a “best of” collection of Kornbluth stories (have run out of room on my bookshelves so some books are in boxes!). There are so many of those “golden age” stories that made a huge impression on me when I read them when I was young—I really need to re-read them.