In Part 1 of What the heck is the “speed of light?”, we noted how light in matter can move much slower than the vacuum speed of light c, or even appear to move much faster than c, under the right circumstances. We even noted that, thanks to the phenomenon of dispersion, there are cases where a single number cannot adequately describe the speed of light of a pulse in matter, because the pulse may break up into multiple pieces, each traveling at its own speed.

All of this may be summarized by saying that a pulse of light is “squishy,” and not a rigid object like a car or a softball. To measure the speed of an object, we look at how long it takes some part of the object to travel the distance from point A to point B. For a car, we can use the front bumper; for a softball, we can use its center of mass. But a pulse of light, which can change shape or break into multiple parts, there isn’t in general a clear mark we can use to define its absolute speed.

This problem of “squishiness” even arises when we look at light propagating in vacuum, and it leads to more unexpected surprises. This is what we look at in this post: the speed of light can be tricky to define sometimes, even in vacuum!

In the previous post, we treated light waves as strictly one-dimensional, i.e. traveling along a line. One-dimensional light waves traveling in vacuum indeed travel at speed c without changing their shape. But we live in a three-dimensional world, and light waves spread out and change shape as they propagate, in a phenomenon called diffraction.

An example is simulated below. We’re all familiar with laser pointers, used in presentations or as a cat toy. Laser pointers produce a highly directional beam of light with a transverse profile shaped like a Gaussian function. If we look the propagation of a very short Gaussian pulse1, roughly 10 femtoseconds in duration, we find that its shape gets distorted as it propagates.

The image shows three snapshots of the pulse as it travels from left to right. As it travels, it becomes wider, and parts of it on the outskirts start to lag behind. This is relatively easy to understand: in order to spread, the some of the light has to move upwards and downwards as well as to the right. If its total speed is c, then it must be moving less than c to the right, making it lag.

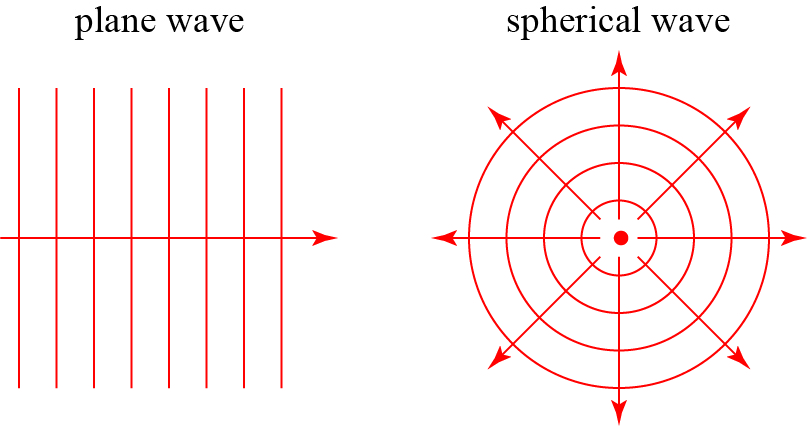

This example shows us that even in vacuum, the shape of a pulse can change and arguably we can say that part of the pulse is moving slower than other parts. You might ask if there are any situations where the speed of light is always, unambiguously c in vacuum, and there are two idealized cases: plane waves and spherical waves2. These are illustrated below: a plane wave is one where the wavefronts (the “up” parts of the wave) are all lined up in a stack of parallel planes, and a spherical wave is one where all the waves emanate from a single point and form spherical wavefronts. Pulsed plane waves and pulsed spherical waves always travel at c in vacuum.

In part 1 of this post, we noted that a temporal pulse is made up of a bunch of different monochromatic (single frequency) waves; this relationship can be made mathematically precise. Analogously, any beam of light in three-dimensional space can either be represented as a combination of plane waves traveling in different directions or spherical waves emanating from different points in space. The former is called the angular spectrum representation, and the latter is essentially the Huygens-Fresnel principle.

We don’t need to know the details of these methods of representing a general beam of light, but these methods show that any beam in vacuum can be represented as a combination of waves — plane or spherical — that all travel at speed c. So, in that sense, every light wave in vacuum travels at speed c, or at least the parts that constitute it do!

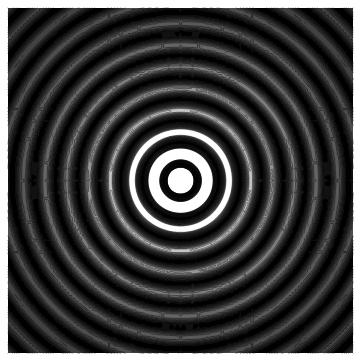

But those “parts” can combine, and interfere, in interesting ways that again confound our expectations about the speed of light. In particular, let’s look at another type of beam, called a “Bessel beam” because the cross-section of the beam has the mathematical form of a Bessel function. If you were to look head on into a Bessel beam, it would look something like the image that follows.

Bessel beams are also known as nondiffracting beams, because an ideal Bessel beam in fact maintains exactly the same cross-sectional shape and size as it propagates. However, an ideal Bessel beam cannot be created, because its rings extend out from the center infinitely, and the result is a beam with infinite energy (which we can’t make). So approximate Bessel beams are generated by truncating the shape of an ideal Bessel beam at a finite diameter — such a truncated Bessel beam is no longer perfectly nondiffracting, but it can be approximately so over significant propagation distances.

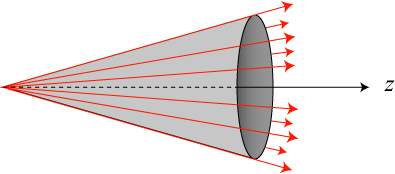

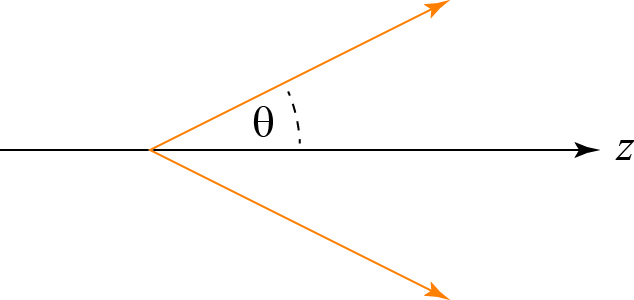

Mathematically, a Bessel beam can be constructed out of a collection of plane waves whose travel directions lie on a cone, as roughly illustrated below.

It is this plane wave structure that, paradoxically, means that a Bessel beam may be considered both to be superluminal and subluminal3 at the same time! Let’s discuss the superluminal part first: in the year 2000, researchers caused an incredible stir4 by noting that the group velocity of a Bessel beam can be greater than the vacuum speed of light! This was quite a shock because, as we saw in the previous post, it is not unusual to see a superluminal group velocity in matter, where gain and loss can result in a group velocity greater than c, but how can this happen in vacuum, where there’s nothing?

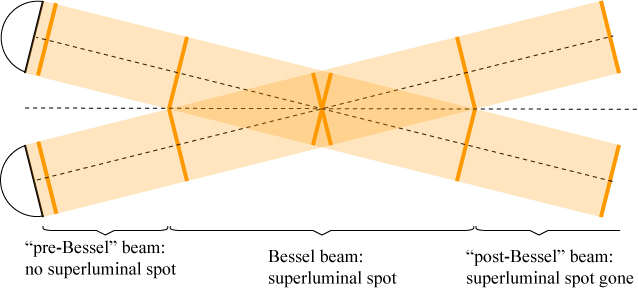

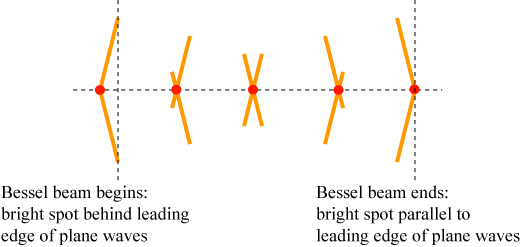

First of all, let us imagine we construct a truncated Bessel beam with a collection of lasers that emit finite plane waves that lie on a cone. We look at how two of them intersect below.

We only get a Bessel beam in the region where the plane waves intersect. The bright spot in the center of the Bessel beam is created where the wavefronts of the plane waves cross. So how fast does this bright spot move? If we zoom in on the intersection point, we see the following.

The red dot shows the relative position of the Bessel beam compared to the leading edge — the front — of the beam. The bright spot starts behind the leading edge of the plane waves and ends at the moment that it catches up to the leading edge of the plane waves. This spot moves faster than the vacuum speed of light, but it is always behind the leading edge of the plane waves, playing “catch up.” Therefore the bright spot cannot be used to transmit a signal, because it is always behind waves that are moving no faster than c!

So the group velocity of a Bessel beam pulse can be greater than c in vacuum, but what about the actual speed, or the signal velocity of the pulse? It turns out that it is slower than c!

As we have seen, the total Bessel beam consists of a bunch of plane waves with directions tilted to lie on a cone. Let us say that the Bessel beam is traveling in the z-direction, and that the angle that the plane waves make with z is θ. Then the speed at which the plane wave moves along the z-direction is, by trigonometry, c cos(θ), which is smaller than c!

This was, in essence, demonstrated experimentally5 in 2015! Researchers in Glasgow and Edinburgh showed that structured light beams like Bessel beams travel slower than c in vacuum! They found that the Bessel beam took several microseconds longer to cross a distance of a meter than something traveling at c would.

So it turns out that, at least in one sense, even light can travel slower than c! This gets me to one of the motivations for the pair of posts on the speed of light: maybe it is a little misleading to refer to c as the “speed of light!” It has always been named as such because light is the first thing we ever encountered that can travel at c, but light can also travel at a variety of speeds, even in vacuum. Perhaps it is better to simply think of c as the speed limit of the universe with light one of the only things that can achieve it?

One last thing: why don’t we usually see these sort of speed of light shenanigans when we talk about relativity? Well, natural light sources typically produce plane waves or spherical waves, which we’ve seen always travel at c. And as for light propagating in matter: we usually don’t move at relativistic speed in the laboratory!

********************************************

- I performed a simulation of a Gaussian pulse using the results from Zhongyang Wang, Zhengquan Zhang, Zhizhan Xu and Qiang Lin, “Space-time profiles of an ultrashort pulsed Gaussian beam,” in IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 566-573, April 1997.

- A third case is a cylindrical wave, but this is rare to find appearing naturally, so it is usually not considered.

- I’ve written about this before, so this post is a bit of an expanded version of the previous one!

- Mugnai, Ranfagni and Ruggeri, “Observation of superluminal behaviors in wave propagation,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (2000), 4830.

- Daniel Giovannini et al. ,Spatially structured photons that travel in free space slower than the speed of light.Science347,857-860(2015).