At first glance, the title of this post probably appears quite paradoxical. After all, the very definition of an object being visible is seeing light coming off of the object! At second glance, you might think the title is referring to infrared radiation or ultraviolet radiation, both of which were discovered in the early 1800s and which lie outside of the visible spectrum of light. But this is also not the case: the tenebroscope is a device that was introduced to demonstrate that visible light is, in a sense, invisible!

I was recently asked to write a retrospective on invisibility for a scientific journal, and I did a search for “invisibility” in the scientific literature in the 19th century to see how that word was used then. I already knew that it was used to describe infrared radiation and ultraviolet radiation, and also to describe particles that are too small to see with the naked eye; this time, however, my search turned up the curious reference to the “Tenebroscope.”

Let’s start with the basics, though: what, exactly, do I mean, when I say light is invisible? This statement seems to be a reaction to some common misunderstandings about light that arise just from observing it in daily life. When I say light is invisible, I mean that it is not itself luminous — light doesn’t give off a glow when it travels, and the only way we can see it is if it actually enters the pupils of our eyes.

Some experiences can give a non-scientist the opposite impression, however. If you sit in a darkened room, you can’t see anything; if you open a narrow hole to let in sunlight, however, the whole room suddenly becomes visible. This happens, of course, because the light reflects and scatters off the walls, finally providing some degree of uniform illumination throughout the room. If one does not understand how light moves, however, one could get the impression that the light entering the room is glowing itself.

This impression can be bolstered by the familiar sight of crepuscular rays, or “god rays,” that peek out from the clouds.

It looks like the light rays themselves are glowing; what is in fact happening, however, is that a small fraction of the light passing through the clouds is being scattered by the atmosphere, and some of that light enters your eyes. What you are really seeing is the interaction of the light with particles in the atmosphere.

So light itself does not glow, which likely seems obvious to a modern viewer, especially since the invention of the laser. A laser produces such a tightly collimated beam that one usually can only see the spot where the beam hits an object (movies such as Star Wars notwithstanding). But apparently in the 19th century this was not so obvious to people, and so the tenebroscope was born.

The device was displayed at the 33rd meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held from late August to early September of 1863 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. The meeting had many distinguished attendees, including James Clerk Maxwell, William Thomson, William Crookes, and Balfour Stewart. There were major reports by committees on subjects such as determining a standard for quantifying electrical resistance, and a large number of short presentations on a variety of topics.

One of the presenters was Abbé François-Napoléon-Marie Moigno, a French Catholic priest and science communicator. Moigno spent a lot of his career helping present scientific advances to the public and translate scientific works into French. At the Newcastle-upon-Tyne meeting, he brought two inventions of one “M. Soleil”; here I borrow from Scientific American’s report1 on the subject:

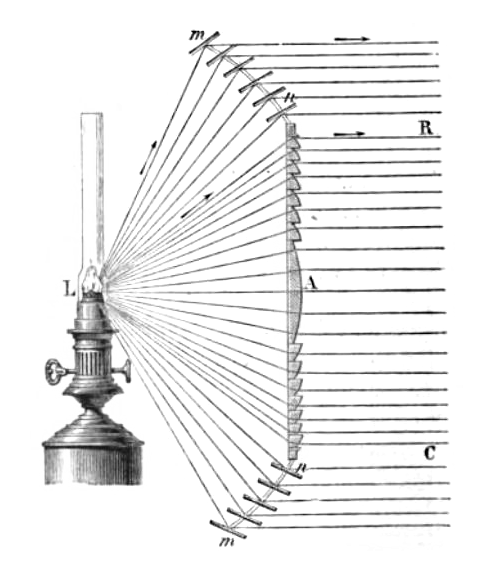

At the last meeting of the British Association, the Abbe Moigno exhibited and described an instrument invented by M. Soleil, of Paris, for illustrating the invisibility of light, and called the “Tenebroscope.” It is well known to scientific men, although the general public do not sufficiently appreciate the fact, that light in itself is invisible unless the eye be so placed as to receive the rays as they approach it, or unless some object be placed in its course, from whose surface the light may be reflected to the eye, which will generally thus give notice of the presence of that object. Thus, if a strong beam of sunlight be admitted into a darkened chamber through a small opening, and received on some blackened surface placed against the opposite wall, the entire chamber will remain in perfect darkness, and all the objects in it invisible, except in as far as small motes floating in the air mark the course of the sunbeam by reflecting portions of its light. Upon projecting a fluid or small dust across the course of the beam its presence also becomes perceptible.

But who is “M. Soleil?” The name is not quite as easy to track down, because “soleil” means “sun” in French so a simple Google search won’t suffice. With some more digging, I believe it refers to Jean-Baptiste François Soleil (1798–1878), a French optical engineer who founded the eponymous company Soleil in 1819 in Paris. He immediately earned great renown by producing the first Fresnel lighthouse lens in 1820 at the request of Augustin-Jean Fresnel, who had received a grant from the French Commission of Lighthouses to develop it. The lens was a success, and Soleil’s hand in its construction clearly made him a respected figure among optical scientists and engineers.

The Tenebroscope was a hit at the British Association meeting, and notices of it appeared in a variety of popular science publications over the next few years. For a description, we turn to the official Report of the 33rd Meeting of the British Association2,

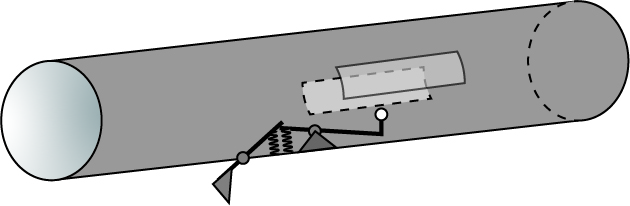

The instrument exhibited consisted of a tube with an opening at one end to be looked into, the other end closed, the inside well blackened, and a wide opening across the tube to admit strong light to pass only across. On looking in, all is perfectly dark, but a small trigger raises at pleasure a small ivory ball into the course of the rays, and its presence instantly reveals the existence of the crossing beam by reflecting a portion of its light.

My rough sketch of this device is shown below.

The two slots in the side of the device would allow only a collimated beam of light to pass through, which would not illuminate the interior of the device unless the trigger is pushed, which raises the ball into the beam, illuminating the entire tube. I was unable to find any sketch of the device in any of the articles I perused, and the “trigger” mechanism I’ve drawn is just a rough guess of how it might work. No description is given as to how the light is collimated to pass through the tube; I could imagine either a beam of light is collimated separately and the Tenebroscope is inserted into the beam, or the scope has long tunnels attached to each of the side apertures, basically collimating any light that happens to be in the room. My guess it the latter, but I’m too lazy to try and draw that version of the device.

You might wonder where the name “Tenebroscope” comes from. To quote from The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal3,

The Abbe humorously observed that this term was somewhat of an Irishism…

Turning to Merriam-Webster for help, an “Irishism” is a term that is synonymous with “Irish bull,” which is “an incongruous statement (such as “it was hereditary in his family to have no children”).” In this case, “Tenebroscope” is a combination of the word “tenebrous,” meaning “dark, murky,” and “scope,” “an instrument for observing, viewing, or examining.” So “Tenebroscope” is a rather oxymoronic way to say it is a device for looking at darkness!

Despite its instant worldwide fame, the Tenebroscope seems to have disappeared quite quickly from the literature; I found no reference to it beyond 1877, other than in the indices of journals, referring back to its brief dalliance with stardom in the 1860s. This means that those people reading this article are probably the first people to be aware of its existence in a hundred years!

Though it did not have a lasting impact, the Tenebroscope shows that there are fascinating tidbits in the history of science that have lingered in obscurity, waiting for someone to dig them up.

**********************************

- “The discoveries of 1863,” Scientific American 10 (1863), 274.

- Abbe Moigno, “M. Soleil’s Tenebroscope, for illustrating the invisibility of light,” Report of the Thirty-Third Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1864), 14.

- The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, volume 18, (1863), 287.

There is no light. It’s just the interaction between matter.

Perhaps the earth is flat too and it’s just the interaction between matter that makes it look round…