It is often the case in science that the human imagination can outpace our technical abilities, and the result is that many remarkable inventions are conceived and their basic principles laid out long before anyone has the capability to construct them.

One great example of this is the idea of a negative refractive index material, which I have talked about a number of times on this blog. Such a material would reverse the normal direction of light refraction, and the possibility that such materials might be constructed was first proposed in 1968 by the Russian physicist Victor Vesalago. However, nobody knew how to make such a material at that time, so it was only around the year 2000 that researchers rediscovered Vesalago’s work and demonstrated that it was now feasible to construct negative index materials, ushering in the modern era of metamaterials in optics.

Here, I want to talk about another example that is a little less well-known. In 1928, the Irish physicist Edward Hutchinson Synge proposed a technique for beating the resolution limit of conventional optical systems, in principle to an arbitrary degree! This work essentially laid out the foundations of what would later be known as near-field microscopy, a significant subfield of optics that only took off in the 1980s, some fifty years after Synge’s first publication on the subject appeared. Synge also earned the approval of a particularly famous scientist in the process of publication, as we will see.

So let’s look at Synge’s remarkable discovery! But first, we should talk a bit about why there is a resolution limit in conventional optical systems, which makes Synge’s work so important.

A conventional imaging system can be boiled down, more or less, to a single objective lens, as illustrated below.

The image shows the path of light emitted by a pair of point objects in an “object plane” and the resulting images of those point objects in the “image plane.” In this figure, “f” is the focal length of the lens.

The biggest takeaway from this figure is the shape of the images in the image plane. It should be noted that they are not point-like, even though the light sources are points. Instead, the images are fuzzy spots. This is due to the wave nature of light: all waves tend to spread out as they travel through space, and this puts a fundamental limit on how much one can concentrate light coming from a point-like source. If the objects are too close together, the fuzzy image spots will overlap, and it will be impossible to distinguish one spot from another. In such a case, we say that the objects are not resolved. This limitation in conventional imaging was studied in detail in the mid- to late-1800s, and so by the early 1900s it was very well-known.

It can be shown (and I did the calculation myself before writing this post just to doublecheck) that the minimum distance that two objects can be spaced and still distinguished (resolved) in the image plane is about one half of the wavelength of light used. The wavelength of visible light is about 0.5 micrometers, which means that one can construct an optical microscope that can image bacteria (with sizes between 1 micrometer to 10 micrometers) but not one that can image viruses (with sizes between 0.005 micrometers to 0.3 micrometers) or DNA (with a diameter of about 0.0025 micrometers).

The most direct strategy to improve the resolution of such an imaging system is to use shorter wavelengths. For example, X-rays have a much shorter wavelength, as do electrons which are used in electron microscopy. However, it is often the case that one specifically wants to determine the response of an imaged object to visible light; for example, one might want to determine the optical properties of the structures within a biological cell. In such cases, a fundamentally different approach must be introduced in order to image objects with visible light at a resolution exceeding the traditional limit.

Such a new approach was introduced by the Irish physicist Edward Hutchinson Synge. Synge demonstrated genius at an early age and studied mathematics at Trinity College for three years; at the end of the third year, he dropped out of school after earning a large inheritance from his uncle. Synge was largely a recluse, but he focused his time in isolation in research on theoretical physics.

Here is where the story gets remarkable. Synge conceived of a novel idea for doing a form of optical imaging with no resolution limit in principle, and on April 22, 1928 he wrote to Albert Einstein about his proposal. The letter can be found in the Einstein papers, and we reproduce a key passage below.

I hardly know whether what I am enclosing may interest you. It is the outline of a method which has occurred to me, and which combines the principles of the ultra- microscope with the method of holding up a picture employed in telephotography, and seems to promise results of no small practical importance, especially in connection with medical discovery. By means of this method the present theoretical limitation to the resolving power in microscopy seems to be completely removed and everything comes to depend upon technical perfection.

Synge then gave Einstein a detailed description of his imagined imaging system. We give an abbreviated description of it here, which is based on the idea of total internal reflection. When light hits an interface going from a dense medium like glass to a rare medium like air beyond a certain critical angle of incidence, it will be perfectly reflected inside the dense medium: it is “totally internally reflected.”

The interesting thing about total internal reflection is that the electromagnetic field is not zero in the rare medium: there exists a field closely bound to the surface and exponentially decaying away from it, known as an “evanescent wave.” This is very roughly illustrated below.

The arrows represent a light wave incident from glass onto the interface at an oblique angle. The fading red represents the evanescent wave, which decays away to almost nothing at a distance roughly equal to the wavelength of light; this will become important shortly.

Let us now suppose we put a small particle, subwavelength in size, on the surface of the glass. The evanescent wave will interact with the small particle and turn into a scattered light wave, in a process known as “frustrated total internal reflection.” We modify our figure to the following one.

The particle therefore acts like a source of light of subwavelength size! However, if we try to image the light from this source using a conventional imaging system, we will run into the same resolution limit that we did before. Here, Synge makes another key suggestion: suppose that we place a slice of biological material on a microscope slide and bring this exceedingly close to the particle. The situation would therefore look roughly as follows.

Synge’s idea may be roughly summarized as follows. The conventional resolution limit of a microscope is due to the fact that light spreads as it propagates from the source or the object to be imaged. By putting the sample right above the scattering particle, the light has not yet propagated far enough to spread! Only a very small section of the sample will be illuminated as light passes through it, and this light can be collected using a conventional lens.

This only accounts for imaging one small spot of the sample; to image the entire sample, the microscope slide must be scanned over the particle, and the collected light recorded for each scan position. In this way, a full image is eventually built up through scanning. Remarkably, this is very close to how modern near-field optical microscopy is done today, as we will discuss.

On May 3, 1928, Einstein wrote a kind and constructive letter back to Synge, discussing his ideas. The letter is available in the Einstein papers, though it is in German; I provide an English translation of the most relevant comments below.

So far I agree. On the other hand, your method of implementation seems to me to be fundamentally useless. If the distance of the layer S from its lower quartz plate is small compared to the wavelength of the applied light, the layer S itself will become the light source, so that the entire field becomes bright.[3] However, if the distance of the layer S from the lower quartz plate and thus from the light source L is greater than the wavelength of the light used, then the achievable determination of the structure of the layer will not significantly exceed the optical resolution in an ordinary microscope.

In principle, this difficulty can be overcome, for example by:

A. The exciting light is invisible and excites the colloid particle, but not the layer S to the people.

B. The light source is light that passes through a tiny hole in an opaque layer

Though Einstein agrees with the basic imaging principle, he notes that the specific strategy Synge proposes will not work: the same frustrated total internal reflection that causes the particle to light up will cause the entire microscope slide to light up! When the microscope slide is brought close to the particle, the evanescent wave will couple back into a propagating wave in the microscope slide, and this will result in a large section of the sample being illuminated, making it a conventional imaging system again.

In this diagram, I have attempted to convey that the evanescent wave between the original glass base and the slide will convert back into a propagating wave throughout the slide, and this interact with the sample over a large area, defeating our goal of illuminating only a small section of it.

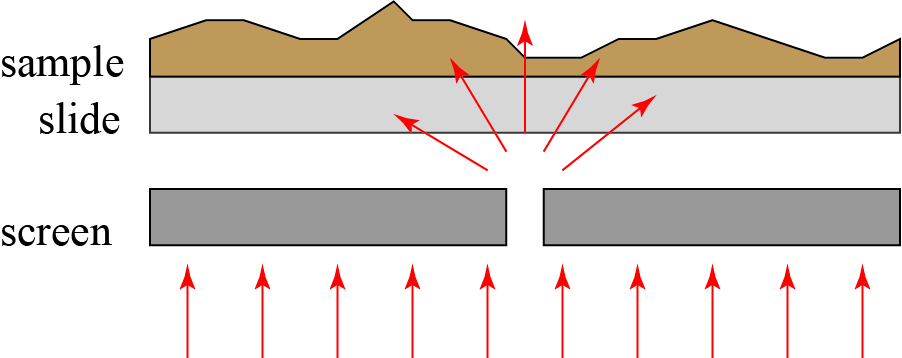

I should stress that Einstein’s criticism is constructive and supportive, and even refers to Synge’s “beautiful idea.” Einstein also proposes a modified version of Synge’s proposed setup, suggesting it could work if “The light source is light that passes through a tiny hole in an opaque layer.” In this case, we replace our evanescent wave and our small particle by a hole in an opaque screen, as illustrated below.

The light emerging from the small hole is spatially localized to a subwavelength region. It will spread rapidly as it propagates away from the screen, but if our sample is sufficiently close (within a wavelength) of the screen, the sample will be illuminated by a spot that is still subwavelength in size. Then, as in the previous iteration, the sample can be scanned over the hole, providing a complete map of its subwavelength optical properties.

This is the approach that Synge ultimately proposed in his paper1, which was submitted on May 25, 1928, mere weeks after Einstein’s letter! We reproduce a key passage from it below.

We shall suppose, also, that a minute aperture, whose diameter is approximately 10-6 cm, has been constructed in an opaque plate or film and that this is illuminated intensely from below, and is placed immediately beneath the exposed side of the biological section, so that the distance of the minute hole from the section is a fraction of 10-6 cm. The light from the hole, after passing through the section, is focussed through a microscope upon a photo-electric cell, whose current measures the light transmitted. The section is moved in its plane with increments of motion of 10-6 cm, so as to plot out an area, the intensity of the light-source being kept constant. The different opacities of the various elementary portions of the section, which pass in succession across the hole, produce correspondingly different currents into the cell. These are amplified and determine the intensity of another light-source, which builds up a picture of the section, as in telephotography, upon a moving photographic plate, the motion of the photographic plate being synchronized with that of the section.

Remarkably, Synge laid out exactly the principles and approach that would eventually be introduced as near-field scanning optical microscopy. However, the technology would take decades to catch up and make the idea practical. The first near-field scanning optical microscope was introduced by Pohl, Denk and Lanz2 in 1984. The small aperture in an opaque screen was replaced by an extremely small quartz fiber coated with metal to make an optical waveguide. Laser light wave sent through this tip, which was then brought close — to within a wavelength — of the sample to be imaged, as illustrated below. Their device was originally called an “optical stethoscope,” as it allows the optical properties of a sample to be localized just like a doctor’s stethoscope allows one to roughly determine the position of the heart in a patient.

Pohl’s paper demonstrated a resolution of 1/20th of a wavelength, far exceeding the traditional imaging limit. Since its appearance, near-field optical microscopy has become its own subfield of optics, albeit a challenging one! Among the practical challenges are the fabrication and manipulation of the fiber probe, which is extremely small and exceedingly delicate. Furthermore, the probe must be kept at a constant subwavelength distance from the sample in order to provide consistent imaging results. In most cases, an atomic force microscope (AFM) is combined with the near-field scanning optical microscope (NSOM) in order to provide precision distance measurements to keep the tip in place.

The earliest researchers into NSOM were apparently not aware of Synge’s paper. This is not surprising, since it appeared some sixty years earlier and definitely much earlier than anyone could have experimentally tested Synge’s ideas! Since that time, however, most researchers into NSOM have recognized and acknowledged Synge’s visionary ideas.

So if you’re a scientist, and nobody seems to be particularly interested in your research results, keep in mind that they might just be way too ahead of their time!

****************************************

- Synge EH (1928). “A suggested method for extending the microscopic resolution into the ultramicroscopic region”. Phil. Mag. 6 (35): 356.

- Pohl DW, Denk W, Lanz M (1984). “Optical stethoscopy: Image recording with resolution λ/20”. Applied Physics Letters. 44 (7): 651.