Book 19 of 26 books for 2024! Can I reach 22 before year’s end?

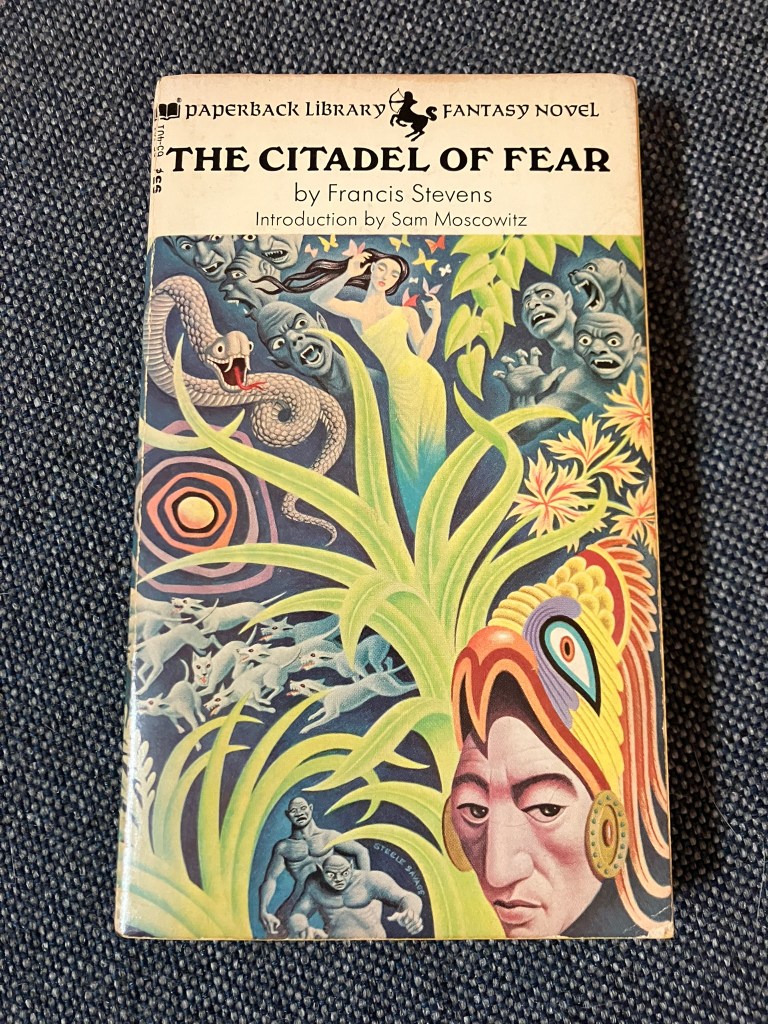

I definitely underestimated Francis Stevens on this one. Stevens was the pseudonym of Gertrude Barrows Bennett (1884-1948), an author of fiction that now tends to fall under the label of “dark fantasy.” Quite a long time ago, I read a complete collection of her short fiction and followed up with her 1920 novel Claimed!, about a man who stubbornly refuses to return the possession of a dark power of the seas. Looking back on those blog posts, that were written some 15 years ago, I found Stevens’ work enjoyable but not exceptional. At the same time, I picked up a vintage copy of her novel The Citadel of Fear, first published in 1920, but somehow didn’t get around to reading it at the time. You can see from the gorgeous cover art why this 1970 edition of the book caught my eye.

As I started the novel, I was initially unimpressed, perhaps distantly remembering my views of previous works of Stevens that I had read. It begins like a rather familiar “lost civilization” pulp adventure story, but then transforms into something… quite different. And clever. And even powerful!

The book begins in a traditional pulp adventure style. Two gold prospectors — Colin “Boots” O’Hara, a twenty-something burly Irishman, and Archer Kennedy, an older and more cynical explorer — are lost and dying of thirst in a remote desert in Mexico. Though strength and determination, Boots manages to drag his colleague to a source of water and, beyond that water, they find a modern plantation nestled in the shelter of a hidden valley. The plantation owner welcomes the men but seems strangely on edge due to their arrival; when night falls, O’Hara and Kennedy sneak out of their room to see what might be hidden by their host.

What they find is a lost but still vibrantly populated mesoamerican city called Tlapallan encircling the shores of a brilliant lake. The city is on edge due to competing factions of the followers of the gods Nacoc-Yaotl and Quetzalcoatl, and the arrival of O’Hara and Kennedy further inflames the rivalry. The men are imprisoned but manage to escape to explore the city, leading to additional troubles, especially when O’Hara meets a beautiful young woman who is betrothed to a follower of Nacoc-Yaotl.

Up to this point, the book seemed like it would go very much the way of other pulp adventures, with the protagonists taking up the cause of one of the city’s factions. But Stevens pulls an unexpected trick on us — Kennedy is sentenced to death and O’Hara is banished from the city, and the book suddenly flashes forward fifteen years. At this time, O’Hara has finally made an expedition back to Tlapallan only to find it abandoned and submerged beneath the lake; he wonders if the entire experience had been a dream. But he has returned to civilization, and enjoys spending time with his younger sister Cliona and her husband David Rhodes. That is, until some monstrous beast attacks the Rhodes house one evening and appears to set its sights on harming Cliona.

Immediately, O’Hara sets out to find the culprit, and lays a trap for the beast if it returns. But something has followed O’Hara back from Tlapallan, a force that is ancient and evil and may take the whole world with it if not stopped in time.

The book does a wonderful job of setting up a minor mystery and lays out the pieces of the puzzle for the reader to put together. The mystery is not too deep or convoluted, and I had figured out certain aspects of it well before they were revealed in writing, but the story is strange enough that I nevertheless found it satisfying and enjoyable. There are a lot of unanswered questions and unexplained phenomena at the point that O’Hara is driven from Tlapallan, and it is nice to see all of those holes get filled in as the novel approaches its climax.

The climax of the novel itself is really beautifully written, and this part blew me away. The various forces that are introduced throughout the book come crashing together in the finale, which becomes a powerful story of good versus evil and a fight over the soul of the — for once — helpless O’Hara. One particularly fun aspect of the finale was its denouement. A police detective MacClellan is introduced in the latter part of the book who is assigned to solve the case of the monstrous home invasion. For the penultimate chapter of the book, we are treated to MacClellan’s baffled report on the unfathomable events he witnessed during the final battle, and his superior’s very skeptical reaction!

So The Citadel of Fear pleasantly surprised me! What at first seemed to be a rather mundane lost civilization story evolved rapidly into something much more intriguing that kept me guessing to the very end.

The book received acclaim from none other than H.P. Lovecraft, who read it when it was first serialized in the pages of The Argosy starting in September of 1918. Lovecraft wrote to the magazine,

Citadel of Fear, if written by Sir Walter Scott or Ibanez, that wonderful and tragic allegory would have been praised to the skies. … Underlying its amazing and thrilling scenes was the sad but indisputable lesson that once a m an gives himself up to evil and to evil deeds only, resulting from selfish greed, that man’s soul is lost. I find also in it a very strong suggestion that real evil does not lie in the so-called personal piccadilloes, but rather in black treachery towards one’s own kith and kin and country, an unmoral endeavor to harm all those who stand in the path of selfish purpose … I feel so much interested in the motif of that curious tale that I should like very much to have my curiosity gratified … would like a sketch of the life of Stevens, and particularly the source and development of The Citadel of Fear. That story would make one amazing moving-picture drama, if taken up by the right moving-picture managers … Stevens, to my mind, is the highest grade of your writers.

(Quote taken from the introduction to the 1970 edition of The Citadel of Fear.)

It is hard to imagine higher praise than that! One can even see, in the clash of unfathomable powers that Stevens lays out, the kernel of Lovecraft’s own later work on cosmic powers and horrors. So it took me some 15 years to get around to reading it, but I am glad that I finally read Stevens’ classic novel.

Later research has discovered that the praise credited to Lovecraft was, in fact, from another Providence resident named Augustus T. Swift. It’s still honest praise, but that does rather undermine its imprimatur.