I’ve talked a lot about polarization recently, including the story of how the best polarizing material was discovered on accident and how modern polarizers made from that material really changed science and technology in a major way. Along the way, I stumbled across the scientific paper that introduced the earliest polarizing device — the Nicol prism. Invented by the Scottish geologist and physicist William Nicol in 1828, it became the standard method of developing polarized light for many years. It is a fascinating device that uses two distinct and unusual optical phenomena together in a clever way, and thought it would be worth discussing his paper and his fascinating invention.

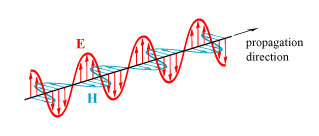

To begin, as I did in the aforementioned posts, let me first say a few things about polarization. Light is a transverse electromagnetic wave, which means it consists of an electric field and a magnetic field, both oscillating perpendicular to the direction the wave is travelling, as illustrated roughly below.

We usually use “E” to represent the electric field and “H” to represent the magnetic field (don’t ask me why we use “H” — I don’t know). As a transverse wave, there are always two distinct ways that a light wave can oscillate. For convenience, we’ll call them “up-down” and “left-right.” We can also describe them by any pair of directions perpendicular to travel, however, such as “upper right-lower left” and “upper left-lower right.”

Natural light sources produce unpolarized light — light that is a combination of up-down and left-right. An ideal polarizer will completely block one of these directions of oscillation; for example, a polarizer oriented to block up-down light will only allow left-right light to pass.

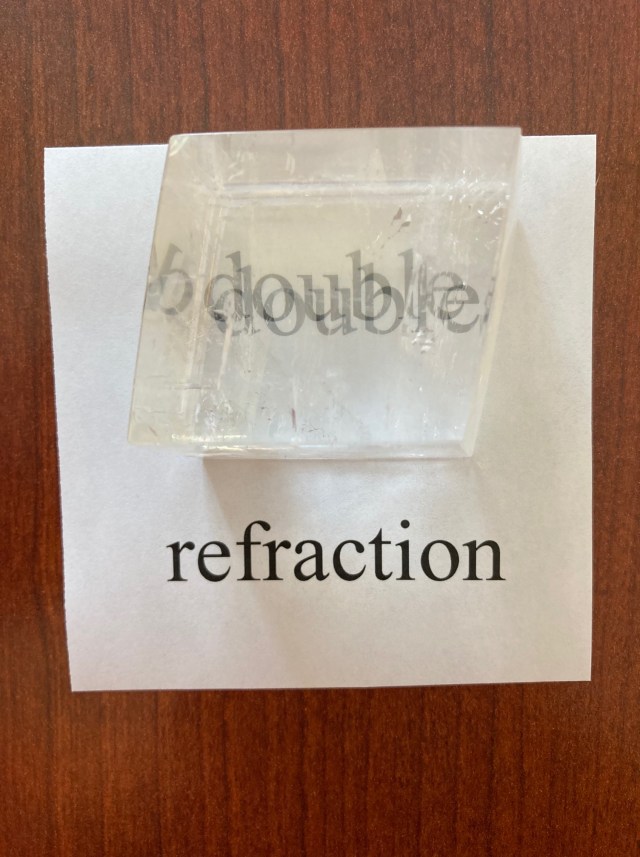

But how did we discover polarization at all? This brings us to the first key ingredient of the Nicol prism — the material optical calcite. In the 1800s, the only known source of it was Iceland, so it is also known as Iceland spar. Researchers at the time were baffled by the observation that two images are formed when looking through a sample of calcite, as shown below.

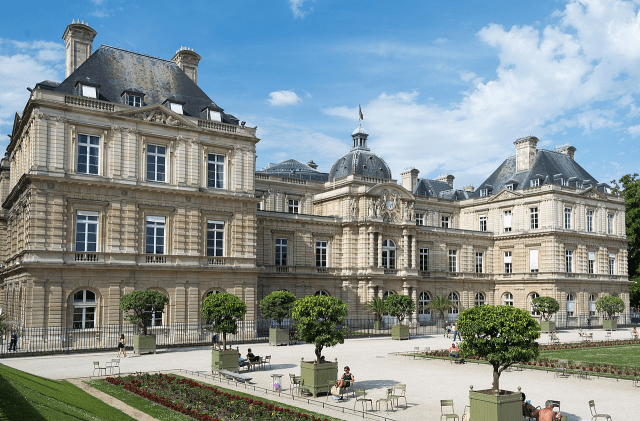

This phenomenon is called double refraction, and it baffled researchers in the early 1800s. In 1808, however, the French physicist Etienne-Louis Malus happened to be looking through a piece of calcite at the windows of the Luxembourg Palace, and he found that by rotating the crystal he could make one of the double images of the sun brighter than the other. Under the right circumstances, he found that only a single image will be produced in calcite, and he called such light “polarized.”

The preliminary explanation for double refraction was penned by the famous Thomas Young in a letter to his French colleague Francois Arago; Young hypothesized, correctly, that light is a transverse wave. It turns out that, in a crystal like calcite, the refractive index of the medium — the angle at which it deflects when entering or leaving the medium — depends on the polarization state. When unpolarized light enters calcite, then, the up-down light and the left-right light get deflected by different degrees, leading to separated images when the light leaves the crystal.

The discovery of polarization led to researchers wanting to study polarized light in more detail. The first method to be discovered was essentially what Malus had accidentally discovered while looking at the Luxembourg Palace — when light reflects off of a surface, the amount of left-right light reflected is different from the amount of up-down light reflected. At a particular angle, known as the Brewster angle, all of the up-down light is transmitted and only left-right light is reflected, leading to perfectly polarized reflected light, as roughly illustrated below.

This phenomenon was studied extensively and quantified by Scottish physicist David Brewster in 1815, and thus now bears his name. Polarizing light by this technique is somewhat awkward, however, and in practice relatively inefficient, so researchers looked for more effective ways to polarize light.

Here we come at last to Nicol’s paper, “On a Method of so far increasing the Divergency of the two

Rays in Calcareous-spar, that only one Image may he seen at a time,” published in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal in 18291. The paper wastes no time in diving right into the heart of the matter:

The following simple method of constructing a prism of calcareous-spar, so that only one image may be seen at a time, will, perhaps, prove interesting to those who are in the habit of examining the optical properties of crystallised bodies by polarised light.

Let a rhomboid of calcareous-spar one inch long be reduced in breadth and thickness to three-tenths of an inch ; let the obliquity of its terminal planes be increased about three degrees ; or, in other words, let the angles formed by the terminal planes, and the adjoining obtuse lateral edges, be made equal to 68°, by operating on the terminal planes : these planes may now be polished. The rhomboid is then to be divided into two equal portions, by a plane passing through the acute lateral edges, and nearly touching the two obtuse solid angles. The sectional plane of each of the two halves must now be made to form exactly an angle of 90° with the terminal plane, and then carefully polished. The two portions are now to be firmly cemented together by means of Canada balsam, so as to form a rhomboid similar to what it was before its division.

My illustration of this construction is shown below.

As I understand it, calcite naturally forms a rhomboid with an angle of 71 degrees; the ends must be cut down to 68 degrees. The crystal is then sliced diagonally so that the two pieces are right-angled triangles, and then they are glued back together using Canada balsam (the grey in my image). Let me come back to what the “optic axis” is in a moment.

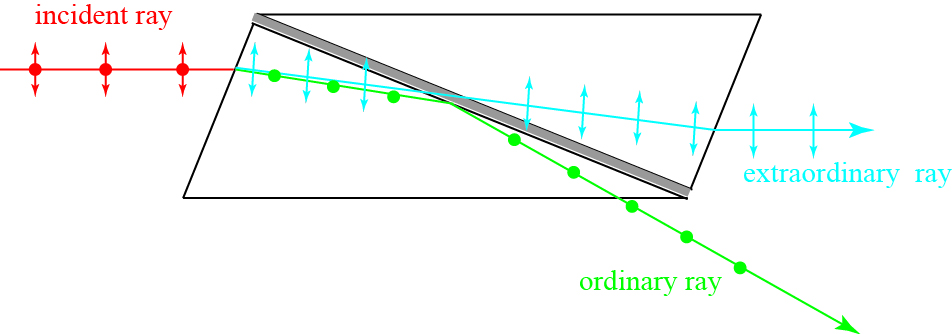

So what happens to an unpolarized beam of light when it enters a Nicol prism? Here is my illustration of the effect:

I actually worked through the geometrical optics to get the angles right — mostly. I didn’t bother calculating the refraction of the ordinary ray as it leaves the prism, and I didn’t bother to calculate the slight bit of refraction that will happen to the extraordinary ray as it passes through the thin layer of Canada balsam. Otherwise, you can see what happens: an unpolarized light ray (in red) breaks up into up-down (blue) and left-right (green) polarized rays upon entering the crystal, via double refraction. The ordinary ray gets completely reflected at the balsam layer, while the extraordinary ray gets (mostly) transmitted.

So why does one polarization get reflected and the other ray get transmitted? The two refractive indices in calcite2 are the “ordinary” index of 1.658 and the “extraordinary” index of 1.486. Canada balsam, in comparison, has an index of about 1.52. When the light impinges on the Canada balsam, the extraordinary ray is going from a low index material to a high index material, while the ordinary ray is going from a high index material to a low index material. The ordinary ray is therefore subject to the phenomenon of total internal reflection: beyond a critical angle that depends upon the indices of both materials.

Total internal reflection can be understood as a consequence of how refraction works. When going from a dense (high index) medium to a rare (low index) medium, light gets refracted more in the rare medium. At a critical angle of incidence, the angle of refraction becomes 90 degrees: the refraction basically starts to reenter the dense medium, and all the light gets reflected.

For the ordinary index/Canada balsam interface, the critical angle is about 66 degrees, which means light has to be coming in pretty close to parallel to the surface to be totally internally reflected. However, from the picture of the rays in the Nicol prism shown above, the ordinary ray is well past the critical angle and so all the ordinary light is reflected out of the crystal. The extraordinary index is of a lower value that the Canada balsam index, so no total internal reflection happens for the extraordinary index.3

The result is that an input unpolarized light beam gets split into two polarized light beams going in different directions. The extraordinary ray, which is propagating parallel to the incident ray, is usually the one that is employed for further experiments.

Before moving on, it is worth explaining a bit of the terminology used here. In a crystal, we can usually define three refractive indices, one for each of three axes of the crystal. In a “uniaxial” crystal like calcite, two of these indices are identical and they result in the “ordinary” ray. The third index is different, and the ray that results experiences an index that is a mixture of the the third index and the identical first two. There is one direction in which both rays have the same refractive index, and that is the optic axis mentioned before. In a “uniaxial” crystal, there is one optic axis, while in a “biaxial” crystal there are two. All of this is relatively unimportant for understanding the operation of the Nicol prism, however.

I find the Nicol prism fascinating because it takes advantage of two unusual optical phenomena working together to produce a polarized beam of light: birefringence and total internal reflection. For years, the Nicol prism was the default device for producing polarized light; as Wikipedia notes, the terminology “between crossed Nicols” is still used today to describe analyzing a polarization-sensitive sample by placing it between two crossed polarizers.

Eventually, the Nicol prism was replaced by other designs of polarizing prisms that were easier to construct and that possessed better optical properties, and later by sheet polarizers like Polaroid. But without Nicol’s clever discovery, the study of polarization and its application in various other fields may have been slowed for decades.

************************************************

- W. Nicol, “On a method of so far increasing the divergence of the two rays in calcareous-spar, that only one image may be seen at a time,” Edinburgh New Philos. J. 6, 83–84 (1829).

- This labeling of indices is a bit oversimplified, as the extraordinary index actually depends upon the direction the light is traveling. It is a bit too complicated to get into the math of this here, so we just treat both of them as constant.

- This is again oversimplified, as the “extraordinary” index is usually a mixture of the two distinct indices of the crystal. We should more precisely say that the extraordinary ray hits the surface at an angle below its critical angle.