I’ve been brushing up on my quantum physics and quantum information science lately, and thought it would be good practice for me to give a little introduction to the idea of quantum cryptography, and one of the first strategies proposed to do it. “Cryptography,” of course, refers to sending coded messages between two people, and the “quantum” part refers to using the inherent properties of quantum physics to make messages harder to crack. This post, then, will be a little bit about the concepts of cryptography and a little bit about the concepts of quantum physics.

We’ll talk about the first protocol for such quantum cryptography first introduced by Bennett and Brassard in 1984, referred to as the BB84 protocol1. My discussion follows my recent read of Stephen Barnett’s book on Quantum Information, which is a very good introduction for physics folks with some background in math and quantum mechanics. The description here, however, will be my own understanding and interpretation, subject to my own still growing understanding of the subject.

To begin, let’s say a few words about cryptography. The goal of every cryptographic strategy is to transmit a message from a sender (called by convention Alice) to a receiver (called Bob) in such a way that the message cannot be decoded by someone who intercepts it along the way (called Eve). The way this is in principle done is for Alice to encode the message with a numeric “key” that describes how the message is encoded, and if Bob has the same key he can reverse the encoding. If Eve does not have the key, then at least in principle she cannot decipher the message. The simplest example is known as the Caesar cypher, in which every letter of a message is encoded by shifting it a fixed number of letters along the total set of letters. In this case, the key is just a single number: the shift applied to all letters of the message. It probably goes without saying that this cypher is extremely easy to crack.

It should immediately be noted that it is in principle possible to design a perfectly encrypted message, using the so-called Vernam cypher. In this approach, a “one-time pad” is generated of a random key that is just as long as the message to be encrypted, so each character in the original message is given its own transformation. Because the key is perfectly random and not repeated, there is no relationship between the original message and the encrypted message and Eve cannot decrypt it. If Bob has the same key, he can decode, character by character, using the same key. That key is never used again, so there is no mechanism to deduce the encoding mechanism. A modified form of this cypher was used by the revolutionary Che Guevara and was found with him when he was captured.

If this cypher is perfect, then what’s the problem? The problem is the distribution of the key itself. The Vernam cypher requires a new key for every message, which means the key will have to be transported from Alice to Bob. This key could be intercepted by Eve along the way, which would make it useless. If the key is a physical pad, then Eve could intercept it, copy it, and send it along; if the key is a radio or optical transmission, Eve could eavesdrop on the signal and thus the key. One could attempt to encrypt the key itself for transmission, but this key would have to be finite in order for it to be transmitted efficiently, and this would make it subject to cracking. If one uses a Vernam cypher to encrypt the key, then one is using a Vernam cypher on a Vernam cypher; hopefully it is clear that this doesn’t solve the problem of key security but “punts” it to the key encryption. The only other possibility is for Alice and Bob to have constructed the key together, in person, before going their separate ways. In some cases this is possible, but in general it is not practical.

The ideal solution would be a solution in which a Vernam-type key can be transmitted between Alice and Bob in such a way that it is not possible to intercept and, if such an intercept is attempted, the tampering can be detected. This is where quantum physics and the BB84 protocol comes in.

The simplest case we can imagine is using individual photons, quantum particles of light, for transmitting information and constructing a quantum key. With that in mind, we first review some basics of “classical” light, i.e. light waves, and then see how focusing on single photons changes our arguments.

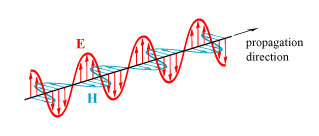

So, as I have said many times before on this blog, light is an electromagnetic wave, which means that it consists of a combined oscillating electric field E and magnetic field H, both perpendicular to the direction that the light wave is going (the propagation direction). We focus on the electric field, which is what is typically measured in any experiment.

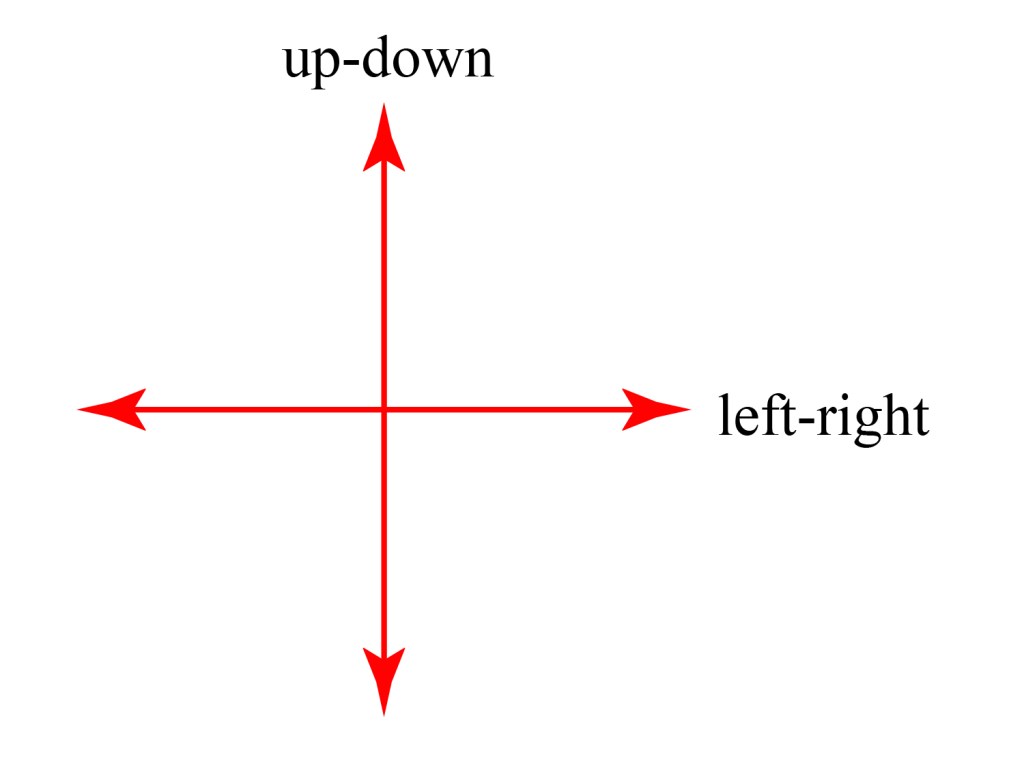

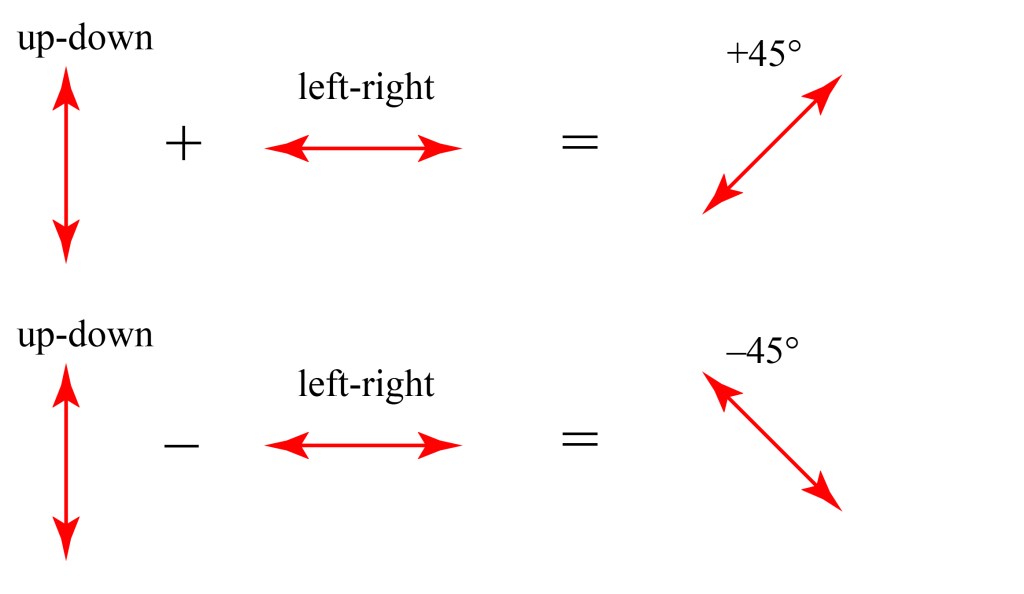

Because light oscillates transversely, we can describe the oscillation direction of a polarized light wave by a combination of two perpendicular states. For example, we can decompose any polarized light wave into a combination of “up-down” polarization and “left-right” polarization. If we are looking head on at the light wave, those two states of oscillation of the electric field can be shown in shorthand as:

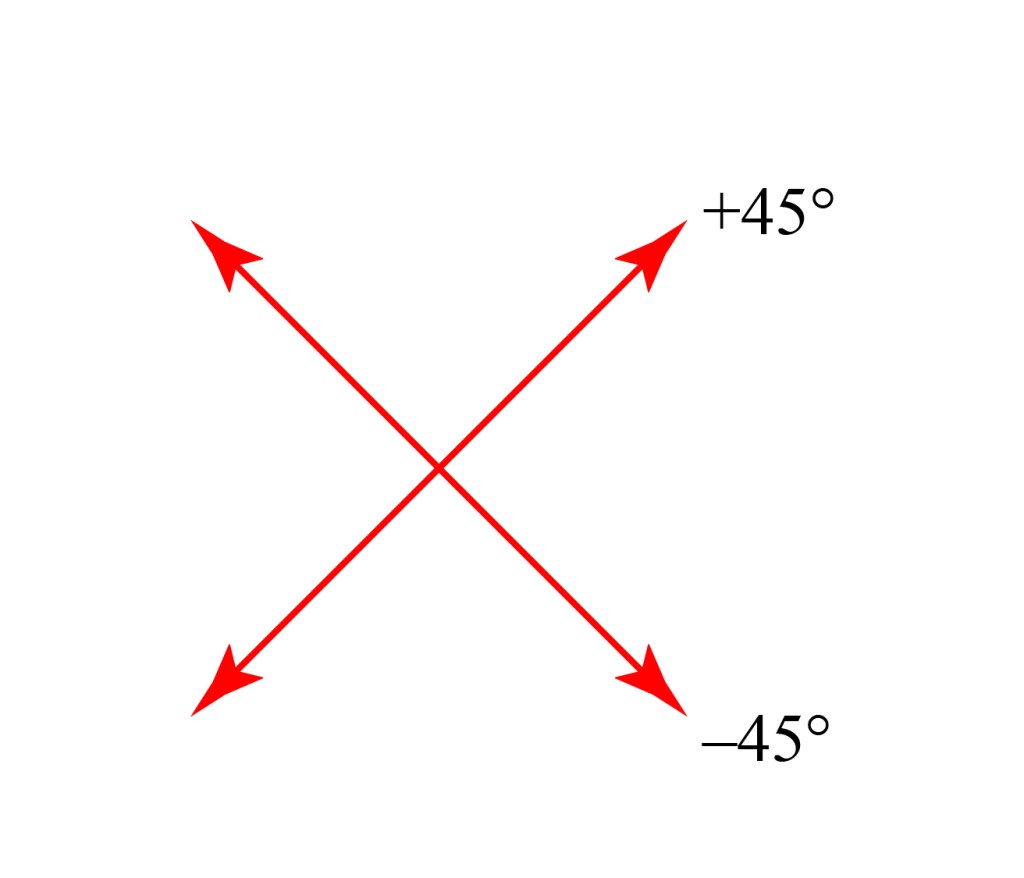

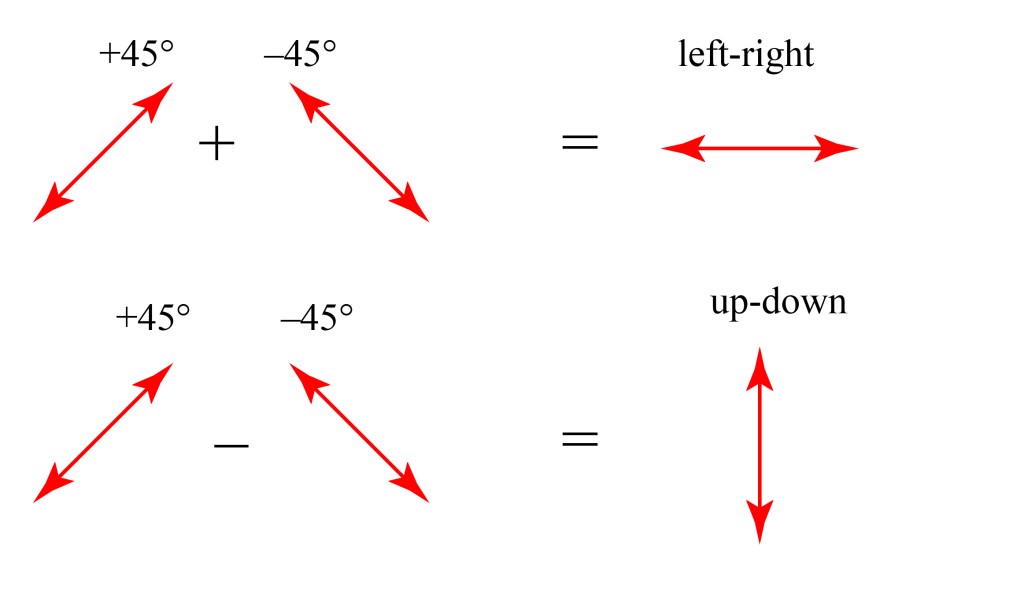

With this choice of states, called a “basis,” we can describe any polarization state. For example, we can write +45 and -45 states as combinations of up-down and left-right:

In other words, up-down plus left-right equals plus 45, while up-down minus left-right equals minus 45. (I won’t go through the details of the math that leads us to conclude this, we’ll just leave it as intuitively reasonable as this is most of what we need for this post.)

But there is nothing special about the up-down/left-right basis; any two perpendicular oscillations can be used to describe any general oscillation. We could, for example, use the two 45 degree states as our basis.

With this basis, we can reverse our previous decomposition and write up-down and left-right as a combination of +45 and -45:

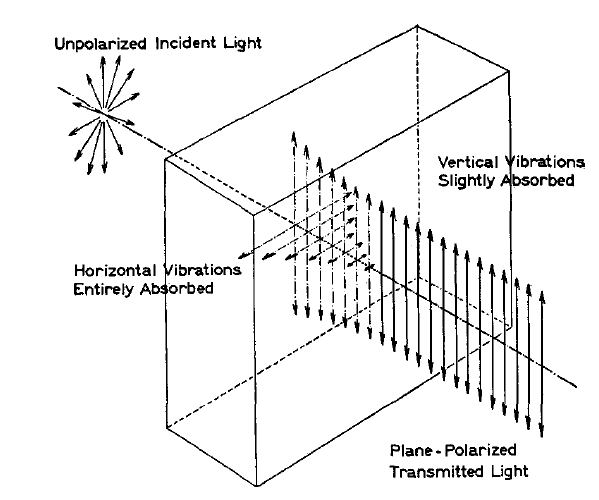

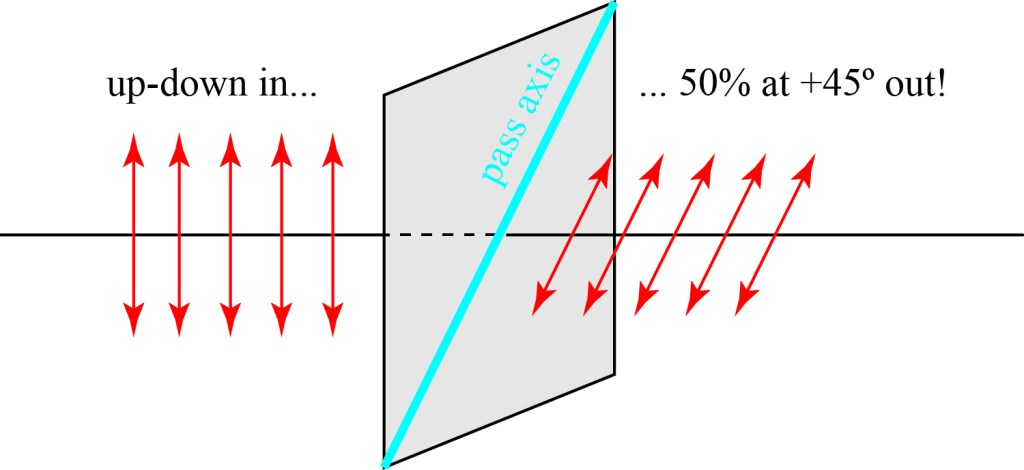

So how do we detect polarization? The easiest way to do it is to use a good polarizer, which will block all the light polarized along one axis while allowing light along the perpendicular axis, which we call the pass axis, to pass through. Below is an illustration from a classic paper showing how a polarizer with a vertical pass axis allows up-down polarized light to go through, while blocking left-right polarized light. (Starting from unpolarized light, which can be viewed as a random mix of up-down and left-right light.)

Let us stick with this polarizer for a moment. If we put left-right light through it, essentially all of it will be blocked; if we put up-down light through it, essentially all of it will pass through. What happens if we put light polarized at 45 degrees or -45 degrees through it? Remember, from above, that each of these polarizations can be considered equal parts up-down and left-right; the result is that the 50% up-down light will pass through and — this is important — the light that comes out will be purely up-down polarized.

Similarly, if we have the polarizer oriented with a pass axis along +45 degrees, and we illuminate it with up-down polarized light, then only 50% of the light will pass through — and it will be polarized at +45 degrees.

What happens if we only have single photons? Obviously, a single photon can’t have 50% of it pass and 50% of it get blocked, so instead in the above picture a single photon polarized up-down and passing through a +45 oriented polarizer will have a 50% chance of passing… and when it does, it will be polarized at +45. We would say that the photon going in has a “quantum state” of being up-down and if it passes through the polarizer it has a quantum state of being +45.

This is a key aspect of quantum physics: the process of measuring a quantum state will generally change it. It will play a big role in detecting eavesdropping in the transmission of a cryptographic key using single photons.

The other key aspect for our quantum cryptography scheme is that we can only perform a definite measurement of the photon polarization if our detector is using the same basis as the transmitted photon. As an example: if a photon is transmitted with an up-down/left-right basis, we will only be able to measure the specific state if our detector (our polarizer, for example) is oriented in the same up-down/left-right basis. If the detector is oriented using the 45 degrees basis, then our measurement will randomly result in either +45 or -45 with a 50% chance of either — the measurement will tell us nothing about the original state of the photon.

To summarize these key results:

- If we measure the state of a photon in the wrong basis, we will change the state of the photon.

- If we measure the state of a photon in the wrong basis, we will get a random result.

- If we measure the state of a photon in the right basis, we will get an accurate result.

This brings us to the BB84 protocol and the strategy that Alice uses to send a key to Bob. Let us, for the sake of sanity, now refer to ‘left-right’ polarization as 0 and ‘up-down’ polarization as 1, and +45 as 0 and -45 as 1. In either basis, then, the two orthogonal polarization states give us a single binary bit of information. Let us also refer to the ‘up-down/left-right’ basis as HV (horizontal-vertical) and the ‘+45/-45’ basis as 45.

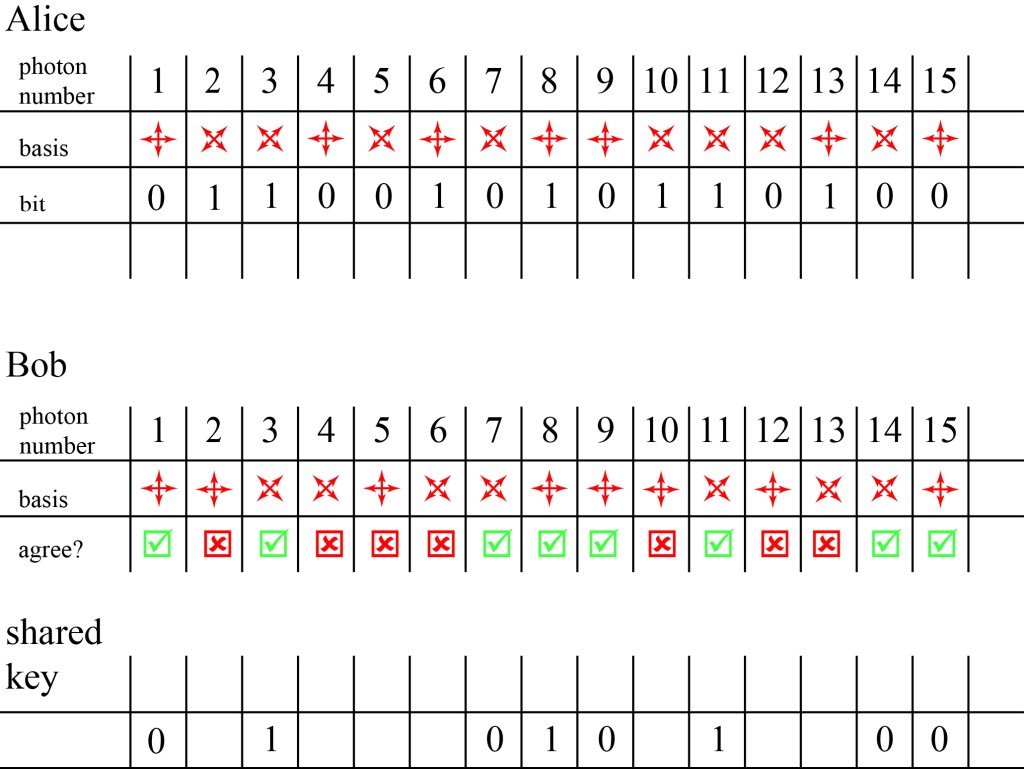

Now Alice sends a sequence of photons to Bob, of a length comparable to but larger than the length of the key needed. For each photon, Alice randomly chooses to use either the HV or 45 basis, and also randomly chooses to set the photon to 0 or 1. On the other end, Bob randomly chooses to measure each photon in either the HV or 45 basis, and records whether he measures a 0 or a 1 for each photon.

If Bob happens to measure a photon using the same basis as Alice, he will properly measure the bit that Alice sent. If he measures the photon using the wrong basis, he will get a random result.

After tallying his data, Bob publicly sends Alice the sequence of measurements that he made on the photons. Alice tells him which of those measurements were in agreement with hers. Alice and Bob know that they have the same binary data for each of those coincident measurements, and that binary data becomes their cryptographic key. The information for every photon that they measured in a different way is discarded. This process is illustrated below for a small sequence of photons.

It should be noted that at no point did Alice and Bob actually publicly share the actual bits of the key, only the measurements that they made to get the key.

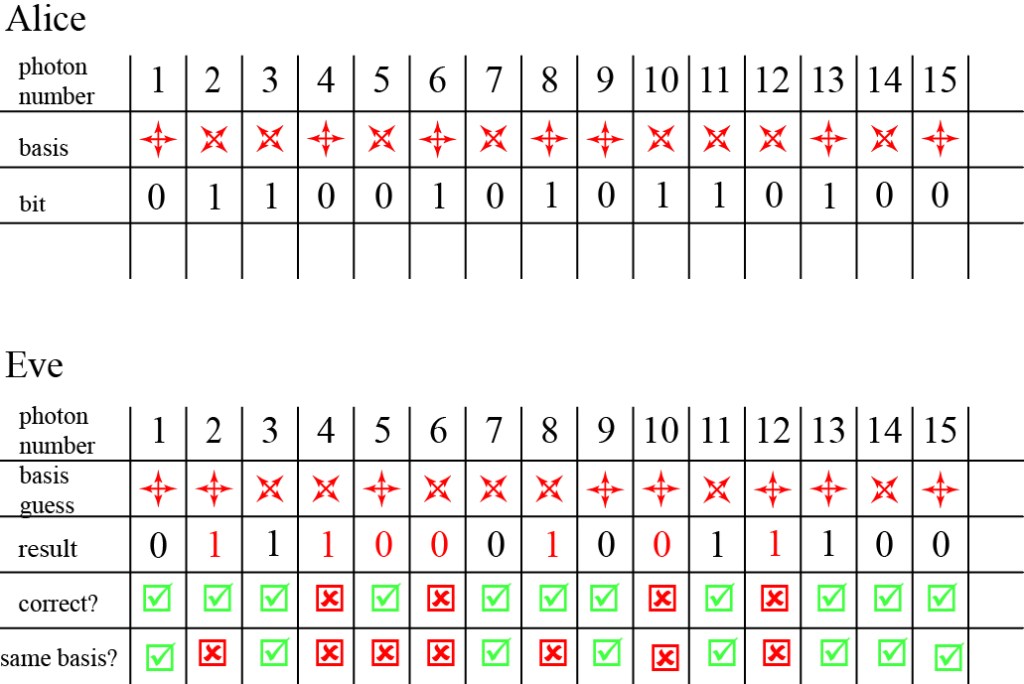

Now let us consider the efforts of Eve to listen in on the communication channel. In order to eavesdrop, Eve will need to intercept each photon as it passes, measure it (which is going to involve absorbing it), and send along a new photon in whatever state she measured the incoming photon. But at this stage, Eve has no way of knowing what basis was used by Alice nor what Alice and Bob will agree on for the key, so she must also guess at the choice of basis to measure in. On average, we expect Eve to be wrong about 50% of the time. A diagram showing Eve’s attempts is shown below.

Every photon that Eve measures in the wrong basis has only a 50% chance of being measured accurately, and Eve has no way to determine if they have been measured correctly or not. So, even though correct results were deduced for about 3/4 of the photons, only 1/2 of them were measured in the right basis, which means that 50% of the measured data is reliable. Unless, by incredible luck, Eve manages to guess the correct basis for almost every photon — and the chance of this approaches zero for even 20 photons — then she will not have the key.

But it goes even further. Because Eve’s measurements change the basis for about 50% of the photons she intercepts, Bob will have disagreements between his results and Alice’s results, even when they compare notes and determine that they were using the same basis. To check for eavesdropping, Alice and Bob take some fraction of the bits where they use the same basis and publicly compare the actual bits. If there is eavesdropping, they will find that their results have significant disagreement and they can terminate the communication attempt before sending an actual message. (These extra bits, whose values are publicly shared, are only used for error checking and not included in the actual key.)

One way that Eve might imagine avoiding this detection is by perfectly duplicating the photons that pass her by. Then she can measure the state of one photon and send the other one along for Bob to measure normally. In fact, if she is able to keep her photon unmeasured until Alice and Bob share their measurement choices, it would seem that she could then use that public information to make the measurements in the correct basis and thus acquire the complete key!

The problem with this is that it is impossible to perfectly duplicate the quantum state of a single photon! There is a fundamental theorem in quantum information known as the no-cloning theorem that states that it is impossible to create an independent and identical copy of an unknown quantum state. The “loophole” in the BB84 method turns out to not be possible at all.

There is one other practical loophole that could be taken advantage of by Eve, however. The analysis above assumes that every photon that is transmitted by Alice is perfectly measured by Bob, and thus that every measurement they make in the same basis is correct. In practice, photons will be lost and noise in the system will produce some errors. Alice can compensate for these errors by sending multiple photons in the same state for a single bit as a form of redundancy. However, the use of multiple photons — and the inherent errors in the system — means that Eve could potentially intercept some of the photons for each bit and hide her presence in the inherent system noise.

With this in mind, there have been many different quantum cryptography schemes introduced since the BB84 protocol. The reader may have noticed that BB84 does not use quantum entanglement at all, even though entanglement is one of the most significant quantum effects out there. Modern schemes, such as one proposed by Ekert2, use entanglement as a means to securely share a key and to detect eavesdropping.

In summary: quantum effects have the potential to create secure cryptographic key sharing, with an added bonus of a means to detect eavesdropping on the shared channel. These schemes all have limits in which the “quantumness” of the system must be highly preserved to get the benefits. However, of all the quantum information science techniques out there, this one appears to be the closest to practical implementation.

***********************************************

- Charles H. Bennett, Gilles Brassard, Quantum cryptography: Public key distribution and coin tossing, Theoretical Computer Science, Volume 560, Part 1, 2014, Pages 7-11.

- Artur K. Ekert, Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem, Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 (1991), 661.