I’ve recently been trying to “relearn” thermodynamics, a subject that I haven’t really looked at, or had to look at, for years. I put “relearn” in quotes because I never really learned it well in the first place! One of my jokes is that every student takes a thermodynamics course from someone who doesn’t really understand it, and then that student goes on to become a teacher who doesn’t really understand it, perpetuating the cycle of educational violence. I’ve been using a book on Basic Thermodynamics by Gerald Carrington that I’ve probably had for 30 years but never delved into in detail; it is a decent book, however, because it has a large number of exercises and provides answers to those questions that are numerical in nature.

It’s been a lot of fun — and a lot of work — trying to relearn these concepts, and I thought it would also be entertaining to talk about some of them here! One of the big fundamental concepts in thermodynamics is the Carnot engine, which operates on the so-called Carnot cycle, named after Sadi Carnot, so let’s take a look at it and why it is of such fundamental importance. A small warning: we’ll do a little bit of math here, but only simple algebra, which we’ll use to prove Carnot’s theorem about the maximum efficiency of heat engines.

A little historical context, as always, is good here. The foundations of thermodynamics were really established in the early 1800s in direct response to the explosive (sometimes literally) importance of steam-powered engines. People knew that these engines produced work through the expansion of heated gases, and also recognized that there were evidently fundamental limits to how much power such an engine could produce. But what are those limits, and where do they come from? Very practical questions like these drove fundamental research into what we now call thermodynamics — the physics of heat and how it relates to other forms of energy.

It is remarkable to note that many of the important results of thermodynamics, including all of Carnot’s results, were derived before we even had a coherent theory of energy and its conservation. As I’ve blogged about before, conservation of energy was really discovered and broadly recognized in the 1840s, while Carnot’s work was done in the 1820s, published in his 1824 book Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire (which I will probably blog about separately). Carnot relied on the idea that heat itself is a fluid that is a conserved quantity, called caloric, to derive his results. Ironically, the strength of the caloric theory comes from the fact that conservation of energy often makes heat look like a conserved quantity, even though it is a type of energy that can be converted to other forms.

To understand the Carnot engine and the Carnot cycle, we should say a few words about thermodynamics itself. Despite the “dynamics” in the name, thermodynamics in general does not work well with systems that are changing rapidly. A thermodynamic “system,” like a volume of gas confined to a box, consists of a large number of molecules, each of which is doing its own thing. We can define certain properties of the system as a whole, such as its temperature, its volume, and its pressure, but these quantities are generally not well defined if the system is in a state of transition. Imagine that we have a volume of gas being heated up by a mechanical stirrer, as roughly illustrated below.

The stirrer is constantly adding energy to the system, which will eventually manifest as heat, but we also might expect that that heat will be deposited near the stirrer and flow outwards. We might be able to measure the local temperature at different locations throughout the box, but the concept of a single temperature for the system as a whole is no longer meaningful. It is only after we stop the stirring process and let the system settle into a steady state — equilibrium — that we can meaningfully define the system temperature again. We can make a similar argument for the pressure of the system.

So thermodynamics — at least in its earliest stages — was all about looking at how systems evolve from one equilibrium state to another. To help with this, two special idealized situations were introduced, known as quasistatic processes and adiabatic processes.

A quasistatic process is a change in a thermodynamic system that happens so slowly that the system may effectively be considered to be in equilibrium throughout the process. One can imagine, for instant, a quasistatic heating process: we allow heat to flow into our system from an external heat bath at such a slow rate that the temperature increases very slowly. That small amount of heat doesn’t significantly disrupt the overall state of the system at any time, so we can treat the system as being in equilibrium until it reaches its final target temperature. Because the system is in equilibrium, any laws that apply to equilibrium systems — such as the classic ideal gas law — can be used; this is why quasistatic processes are important — we can directly do mathematical calculations relating to the process.

An adiabatic process is a process where no heat it transferred into or out of the system — it is thermally insulated — and only mechanical work can be done on/by the system. For example, if we take a volume of gas in a thermally insulated box and squish the box, shrinking its volume, we are doing work on the gas in the box. Though we won’t get into it here, adiabatic processes are important because the entropy of the system is constant throughout the process. Again, this makes certain calculations relating to the process possible to do.

One more concept is important to mention at this point — irreversible processes. A thermodynamic process is irreversible if its action on the system cannot be undone without leaving some sort of change in the surroundings. A classic example of an irreversible process is the free expansion of a gas. Imagine that we have a gas confined to one half of a box by a sliding barrier, and then we quickly slide that barrier out to let the gas freely flow to fill the entire box. Can we reverse this process? If we have a sliding piston wall within the box, as illustrated below, we can return the gas entirely to the left side of the box, but we have to do work — spend energy — in order to push against the pressure of the gas. That expenditure of energy is our change in the surroundings. That work has, in turn, been transferred to the gas in the form of heat, so the gas is hotter as well.

Carnot sought to find an idealized cycle — a system of processes that return to their starting condition — that is reversible, i.e. that could be fully undone by reversing the steps. His result is what is known as the Carnot cycle, which we illustrate schematically and describe in words below.

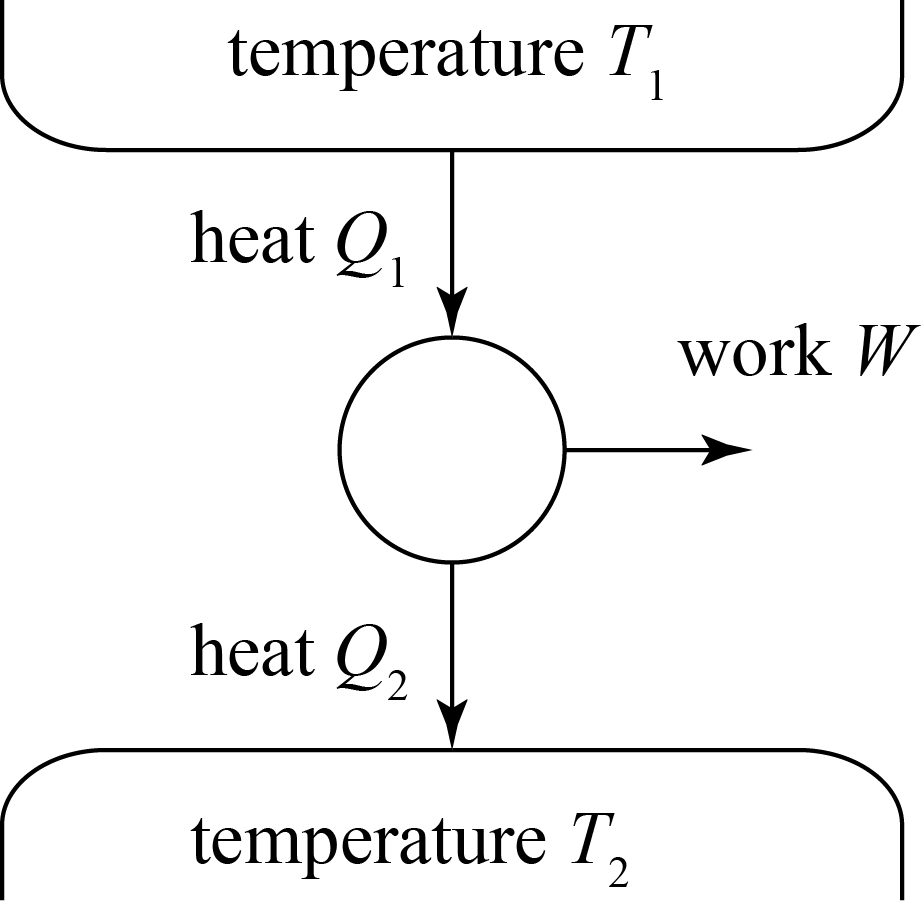

This figure indicates that the cycle, or the engine that actually carries out the cycle, will draw an amount of heat Q1 from a heat bath at temperature T1 and produce an amount of work W from it, with an amount of waste heat Q2 going to a heat bath at temperature T2. The thermodynamical system of our Carnot cycle is a gas; the actual steps of the cycle are:

- Isothermal expansion of gas at temperature T1. We connect our gas to the heat bath of temperature T1, allowing heat to flow into the system and to cause the gas to expand, which can do work. The temperature is constant throughout due to the connection to the heat bath.

- Adiabatic quasistatic expansion of gas. We now disconnect the gas from the heat bath and allow it to expand quasistatically.

- Isothermal compression of gas at temperature T2. We now connect the gas to the cold temperature bath of temperature T2, and the gas starts to compress while at a fixed temperature.

- Adiabatic quasistatic compression of gas. We disconnect the gas from the cold bath and allow it to continue compressing.

Because heat only flows into/out of the gas in steps 1 and 3, and energy is conserved, we can determine the amount of work this engine does based on knowing the values of Q1 and Q2. We are aided by a relationship that the Carnot cycle satisfies but that we will not prove here:

.

Proving this requires us to apply some calculations involving entropy, so we’ll just take it as a given. This result by itself indicates that if T1 is relatively large, Q1 will be relatively large and we’ll get more work out of the system.

The Carnot cycle is in principle reversible, because we can run the engine in reverse to move heat from the cool bath to the hot bath by inputting the work W. This will be crucially important in a few moments.

To do a little more math, let us define the efficiency of the cycle by the expression:

.

A hypothetically perfect cycle would convert all the input heat Q1 into work W and would have . We don’t expect that to happen in general, and we would like to determine the efficiency of the Carnot cycle. We can add to the previous two equations the statement of conservation of energy (First Law of Thermodynamics):

,

Which says that the heat flowing in must equal the sum of the work going out and the heat flowing out. We solve this equation for W and plug it into the efficiency equation to get

where the last step comes from the first equation above. Finally, we simplify to find the efficiency is

.

This is a very simple result but a quite remarkable one. It says that the efficiency of the Carnot cycle is entirely dependent upon the temperatures of the two heat baths and not on any other quantities.

This may seem pretty uninspiring as you may have already deduced that most engines — like, say a steam engine or your automobile engine — do not act in a quasistatic manner. These engines are cycling very quickly! The remarkable aspect of the Carnot cycle, however, is that we can prove that it represents the maximum efficiency of a heat engine operating between two heat baths. It provides an upper limit on what is possible with heat engines.

To prove this, let us imagine that we have two engines, a Carnot engine and an engine whose efficiency we want to test. Because the Carnot engine is reversible, we can run it as a refrigerator, and we put the two engines together, with the output of our test engine t being the input of our Carnot refrigerator c.

We need one more important law to perform our proof: the Second Law of Thermodynamics. In the statement of it by Clausius, it is of the form:

No engine working in a cycle can transfer energy from a cold body to a hot body and have no other effect.

In broader terms, heat does not spontaneously flow from colder objects to hotter objects, a statement that is plausible on the basis of lived experience.

Now what is the ratio of Qc and Qt, the heat drawn by system t and deposited by system c? We may write

,

where we have taken advantage of the fact that the work is the same for both systems and that the efficiencies are defined by the ratio of work over input heat.

Now let us suppose that , i.e. that our test system has greater efficiency than the Carnot system. Then we will find that

, or that more heat is being transferred to the hot bath by the Carnot system than is being drawn by the test system. Because the work output of one is perfectly transferred to the other, we can say that we have violated the Second Law in Clausius’ statement! We will have a system that will spontaneously transfer heat from a cold body to a hot body without any other effect, much like Maxwell’s hypothetical demon.

We have found that . Now let us suppose our test system is also reversible; we can then swap t and c in our picture above, and we can find that

. Therefore, if our test system is reversible, it must have exactly the same efficiency as a Carnot engine, i.e.

!

We may therefore state the conclusion of Carnot’s theorem as follows:

If a system is reversible, its efficiency is equal to the efficiency of a Carnot system. If a system is non-reversible, its efficiency is less than the efficiency of a Carnot system.

Carnot’s theorem quantifies the absolute limit of a heat-based engine, putting a hard limit on what is possible and not possible with such an engine. The efficiency expression for the Carnot system itself shows that the efficiency only depends upon the temperatures of the heat baths involved.

Carnot’s theorem is a great illustration of how early thermodynamics straddled abstract theory and extremely practical applications. Contrary to my initial impressions as an undergraduate student, it is a really fascinating topic!