One of the topics of the history of science that has continued to fascinate me is the discovery of the principle of conservation of energy. As I discussed in my three-part series “Booms, Blood, and Beer” (part 1, part 2, part 3), some of the key discoveries were made by the most unlikely of investigators: a cannon-borer Count Rumford (booms), a physician Julius Robert Mayer (blood) and a brewer (beer).

The story of Mayer in particular has always fascinated me. He was a German physician who decided, after earning his license to practice medicine, to work as a ship’s doctor on a Dutch merchant ship sailing to Indonesia in 1840. While on the trip, he spend a lot of time observing and pondering nature, and some of his observations got him thinking about a law of conserved “force” that would be a philosophical complement of sorts to the law of conservation of matter. One key observation for him was seeing that, during a standard bloodletting of the sailors when they arrived in Jakarta, the venous blood was much redder than he was used to seeing in Europe. In discussions with other doctors, he learned that this is because less oxygen is consumed to heat the body in the hot climate of Indonesia than in the chilly northern parts of Europe.

This mechanism was already known by science at the time, but it triggered a train of thought in Mayer that became his obsession. At the time, there was much discussion about the nature of heat: what is it that makes some things warmer than others? The prevailing theory was that heat is its own physical fluid, called caloric, that could be released from a substance by friction or combustion. Also known but less popular was the (correct) theory that heat is simply the collective random motion of atoms and molecules. Heat spreads because some of those “hot” molecules collide with neighboring “cold” molecules and transfer their energy to them. Mayer’s thoughts about the generation of heat by the human body led him not only to consider heat a form of motion, but to postulate that there is a conserved “something,” that he called “force,” that could be used to unify thinking about physical phenomena throughout nature, from simple collisions of inanimate objects to the workings of living creatures.

Mayer was complete correct on the general principle, but he was no physicist. His early attempts to create a theory of what would eventually be called conservation of energy were crude and inaccurate — but contained the kernel of a truth that had never before been successfully elucidated. After submitting his first paper for publication (which would fail), he wrote to his scientist friend Carl Baur to explain his ideas and get feedback, where he first wrote what I call “The most beautiful wrong equation in history.”

In this post, we go through Mayer’s first (translated) letter to Baur and see how even incorrectly formulated ideas can be amazing — and beautiful. I used Google Translate along with some very crude understanding of German to handle the translations. The translations come from an 1890 book of Mayer’s collected papers.

This first letter was sent to Baur from Mayer in Heilbronn, Germany on July 24, 1841. Mayer had returned from his trip to Jakarta in February and had wasted no time putting together an article on his ideas, which he sent off to the famed journal Annalen der Physik for consideration.

Dear friend!

Above all, please accept my thanks for the efficient procurement of the addresses from Paris, which rightfully belong to my brother; may you find it convenient to make use of my services whenever necessary. And now for others. My friend Kehrer told me he had discussed with you a system of physics that I brought back from my travels, and that you had shown interest in it. I now gladly seize the opportunity to share my thoughts, which have become a profound conviction for me, with an expert, naturally assuming, however, that you will not tell anyone else, since, understandably, I do not wish to create any competition in the publication of this matter.

Mayer gets right to the point — he had shared some of his ideas with his friend Kehrer, who had in turn shared them with Baur. Baur was interested in learning more. Here we see that Mayer is happy to share, though in confidence for fear that his claims might be disputed by others (a fear that would turn out to be prophetic).

Starting with physiological and pathological investigations, where it seemed to me that I had arrived at sound principles, I was, by consistently pursuing these principles backwards, necessarily led into the fields of chemistry and physics. This process gave rise to a view of nature that completely illuminated for me an immense and truly endless series of hitherto inexplicable phenomena, and which, besides the fields of natural science and special medicine, also resolves the most important questions of metaphysics. You will exclaim with laughter: “A lot at once!” But I confess to you that this research constituted the sole focus of strenuous activity throughout my entire journey and now also since my arrival here, and that this alone, and this alone, more than compensated me tenfold for all the hardships, etc., of such a long journey. Having foolishly expended everything to exceed your expectations, I will now explain the matter itself to you.

This is such a delightful paragraph. He hints at the physiological origins of his curiosity, and then notes how even the concept of a conservation law suddenly made so many physical phenomena make more sense! I like how he acknowledges how ridiculous this must sound, though history would find him fully justified.

The chemist firmly adheres to the principle that the substance is indestructible, and that the constituent elements and the compound formed are in the most necessary relationship; if H and O disappear (qualitatively become 0) and HO appears, the chemist must not assume that H and O actually become 0, but that the formation of HO is accidental or extraneous; modern chemistry is based on the strict application of this principle, and apparently, this is the only way to achieve well-rounded results.

Here he uses one of the most powerful tools in the early physicist’s toolbox: analogy. Chemistry has shown that new chemicals come from rearranging the constituent parts of other chemicals, and that the matter itself is not created or destroyed, but just organized in new ways that may make it unrecognizable. Here, his reference to “HO” presumably means “H2O” and one imagines that he was not versed well enough in chemistry to know the difference.

His statement “but that the formation of HO is accidental or extraneous” sounds odd, and seems to be an accurate translation from the letter, though one imagines he meant “or that the formation of HO is accidental or extraneous.” With personal correspondence, this may very well have been a mistake in writing on Mayer’s part in the original letter, or a mistake in transcription to the book.

We must apply precisely the same principles to forces; they, like substance, are indestructible, they, too, combine with one another, thus disappearing in their old form (becoming qualitatively zero), and reappearing in a new one. The connection between the first and second forms is just as essential as that between H and O and HO. The forces (whose rigorous philosophical development I will not neglect as soon as you wish) are: motion, electricity, and heat.

Here we have the foundation of Mayer’s entire new philosophy: that “forces” are indestructible, and that what appears to be the disappearance of one force is simply its conversion into another type. He explicitly links motion, electricity and heat as fundamental forces that can convert into each other.

It is impossible to understate how huge this argument is. Mayer was proposing a complete unifying principle for all of nature. Indeed, it was “A lot at once!”

His use of “force” is inaccurate in modern parlance; he really is referring to what we might call “a quantity of motion.” Force in physics is today used to describe an effect that causes a change in motion; this confusion of terminology would persist for decades, finally being mostly sorted out in the 1860s, when the term “energy” would be properly defined and made distinct from “force.”

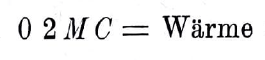

A motion + MC, canceled out by an equally large but directly opposite motion – MC, yields, because both motions (like the substance) are quantitatively unchanging, 2 MC, but with the sign (qualitative determination) 0. We obtain 0 2 MC, which is heat. This is the theoretical development of the old empirical principle that heat is generated by friction; naturally, this only applies in dynamics and not in statics, because only in the former does the actual motion MC occur. From what has been said, we arrive at the proposition: when motion decreases and ceases, a quantity of force with a different quality is always formed, corresponding exactly to the vanishing quantum of force (motion), namely, heat. From this follow: the doctrine of vibrating motions, the conductivity of substances for motion, i.e., elasticity; everywhere the established fundamental principle is the sure guide.

Now we get to the meat of the new theory: the math. But it is also woefully incorrect math, though this is not surprising considering a) it is an entirely new theory and b) Mayer was no physicist! He introduces what we could call the “energy” of motion of an object moving in a positive direction as + MC, where M is presumably the mass of the object and C is the speed of the object. Those who know a little physics will recognize that P = MV, where M is mass and V is speed, is the formula for the momentum of an object. The kinetic energy K of a moving object has the form,

which Mayer would figure out in later investigations.

In this early argument, Mayer asks us to consider two objects colliding head on with equal masses M and opposite velocities +C and –C. We know from experience that these two objects will stop dead on collision; before conservation of energy was discovered, most researchers did not think any further about where that motion “went.” Mayer argues that the total quantity of motion, 2 MC, must still be present, but that it now has converted into heat. For lack of a better notation — recall that Mayer was no physicist or mathematician — he wrote this heat as 0 2 MC, with the “0” representing that there is no net direction of motion associated with the conserved quantity, i.e. no + or -!

Mayer elaborates on this in the next paragraph:

The expansion of a substance due to heat is contained in the formula for heat 0 2 MC, which, through the quantitative symbol 0, indicates that motion does not predominate in any direction, i.e., that every conceivable positive motion corresponds to an equal negative motion, etc. The formula 0 2 MC is generally suitable for vibrating and wave motions; the difference between these and heat is only qualitative. Heat does not arise as long as the motion continues in waves according to its quantum; for, as I repeat: heat is motion that has become qualitatively zero.

Here he explicitly states that heat is motion; the “0” in his formula means that for every “+” motion in every direction there is an equal “-” motion. “Heat is motion that has become qualitatively zero” is a statement that sticks with me.

Mayer then introduces a very unusual equation, which I will try my best to interpret:

If we set

x denotes the energy of motion;

gives the formula for light; this is

.

Everything said about movement and heat also applies to light, which is nothing but movement of extraordinary energy.

These formulas are a little baffling, but here’s my best guess! In the first formula, he is noting that one can have the same “force” (energy) for a wide variety of masses/speeds. If one imagines the mass decreasing by a divisor x, one can get the same energy by increasing the speed by a multiple x. If one imagines a massless, very fast object, say light, then one can argue that the same formula applies, since the mass approaches zero and the speed approaches infinity.

This does not really work at all in the context of modern physics, where light is indeed massless but the speed of light is very fast but finite, but it is nevertheless an extraordinary argument because he is saying that motion can be transformed into light and vice-versa.

Unifying various fundamental physical phenomena was clearly Mayer’s goal; he then turns to make a brief statement about electricity:

As far as electricity is concerned, let it be said in anticipation of the following:

i.e.

quantitatively, the difference is only qualitative; the development of the theory of electricity according to these principles is of particular importance, I am currently dealing with it primarily.

The math here again does not really work, but it is incredible that Mayer had connected the idea that one could connect a certain property of electricity to a certain amount of heat or motion.

It is this first equation above, or at least the first half of it, that I would like to call “the most beautiful wrong equation in history.” If I keep only that first half from the original document, we have:

This is, to the best of my knowledge, the first time that someone attempted to convey, in a quantitative manner, the general idea that mechanical motion is equivalent to heat, in the sense that one can be converted into another. The details of the equation are, of course, absolutely wrong, but this represents a magnificent milestone in recognizing that there is a fundamental conservation of “forces.” I look at this with the same sort of awe that I had seeing and understanding for the first time what Einstein’s E = mc2 means. The difference of course is that Einstein’s formula is quantitatively correct, while Mayer’s is not. However, Einstein had the benefit of some 50 years of recognition of the conservation of energy, something Mayer did not.

Mayer’s letter continues, so in the interest of completeness, let’s finish it; there’s not much left!

The parallelogram of forces, in dynamics (not in statics), requires a significant correction based on what has been discussed so far: the doctrine of the neutralized force, which was overlooked when the motion was composed and erroneously assumed when the diagonal was decomposed into its (together larger) enclosing sides. This has important consequences for the laws of central motion; in short: the central body behaves as falling relative to the periphery, just as the peripheral bodies behave as falling relative to the center; this is the cause of the evolution of light.

Mayer appears to be discussing the vector addition of object momentum, where one can determine the total momentum from the vector sum of the momenta of the individual objects. Mayer seems to be saying here “sure, you can add the momenta to zero when two objects collide, but the effect of that motion lives on in heat which is not accounted for in the existing formulas.” I am not sure at all what he’s getting at with the “laws of central motion” afterwards, however.

Thus, I have now briefly shared some of my results with you; numerous attacks against what I have stated are inevitable, but through long and thorough research, I have become too convinced of the objective truth of what I have said to be at a loss for defenses; every objection will be welcome. Of course, there are objections that may require extensive discussion; however, I will engage with everything, whether it be philosophical definitions or demonstrations in a very specific practical context.

It would have been very tempting back in the day to imagine Mayer as a typical science crank, which I am sure existed back then as well. The one thing that separates him from the typical crank is his humility. He recognizes that he has a long path ahead of him to convince others that he is correct, and he is eager to have strong feedback.

Once I have finished dealing with the objects of inanimate nature, which I intend to treat as cursorily as possible, my intention is to develop a more coherent system of living nature based on this.

Mayer was first inspired to develop his theory through observations on living creatures, and that is where he intended to return; he would find much more fruitful results in physical science.

I recently submitted the above information to Poggendorff for his annals in the middle of last month; I have yet to receive a reply. It would therefore be a great favor to me if you would check whether the article has already been printed, because otherwise I will be pressing Poggendorff for a response, which I requested again three weeks ago. I eagerly await your comment on what I have said and once again advise you to maintain discretion towards everyone.

Poggendorff was the now legendary editor of Annalen der Physik, the premiere journal at the time. In what was really a shocking breach of protocol, Poggendorff would not only not publish Mayer’s article but would never return it to Mayer. In an era when submitted manuscripts were hand written and no simple copy method existed, this was stunningly rude. It is perhaps not surprising that Poggendorff paid little attention to Mayer’s work, though: as we have noted, it was incomplete and full of incorrect ideas, even though the kernel of brilliance was there. Incredibly, Mayer’s original paper was found still on Poggendorff’s files when he died, so we are able to read that flawed work today.

Mayer’s failure to get published in Annalen der Physik would turn out to have a devastating effect on his life and scientific career. He later got his work Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, where it was overlooked by the broader scientific community. This would become catastrophic when James Joule, in 1843, published his own independent discovery of conservation of energy. This led the British scientific community to rally around Joule in nationalistic pride and destroy Mayer’s reputation and even his sanity. The cruel treatment of Mayer is incredibly tragic, but it would take an astonishing turn decades later when the Irish physicist John Tyndall would come to his rescue in a particularly dramatic fashion; I have blogged about this story in detail before.

I feel that we are very fortunate to have a lot of Mayer’s early letters, which not only highlight the history of one of the most important scientific concepts ever but also show how discovery is often a process of going from flawed and simplistic initial ideas to the beautiful truth.

I think that I understand the point of Mayer’s expression . He wants a directed quantity whose magnitude is

. He wants a directed quantity whose magnitude is  but whose direction is

but whose direction is  rather than

rather than  or

or  . Unfortunately, vectors don’t work like that. This seems connected to Mayer’s issues with vector addition near the end.

. Unfortunately, vectors don’t work like that. This seems connected to Mayer’s issues with vector addition near the end.

What Mayer didn't realize is that there's both a directed quantity of motion (momentum) and an undirected quantity of motion (kinetic energy). These are numerically different, since the first is proportional to velocity and the second to the square of velocity (which you hinted that Mayer eventually realized). But more importantly, momentum adds as a vector, so that and

and  add to

add to  , while kinetic energy adds as an unsigned scalar, so that

, while kinetic energy adds as an unsigned scalar, so that  and

and  (with no

(with no  or

or  ) add to

) add to  (and secondarily

(and secondarily  here is half the square of the velocity rather than the velocity). That

here is half the square of the velocity rather than the velocity). That  energy can then be converted as heat while the momentum remains

energy can then be converted as heat while the momentum remains  .

.

Artikelnya sangat membantu dan relevan dengan kebutuhan perjalanan saat ini.

Referensi Travel Chrter Mobil Paket Kilat ini juga cocok untuk pembaca yang ingin perjalanan lebih nyaman dan praktis.