Here’s another post based on the revisions I’m making for the second edition of my Singular Optics textbook! Caustics are a subject that I’ve sort of casually understood for ages but never well enough to explain it, but book work has finally made it possible.

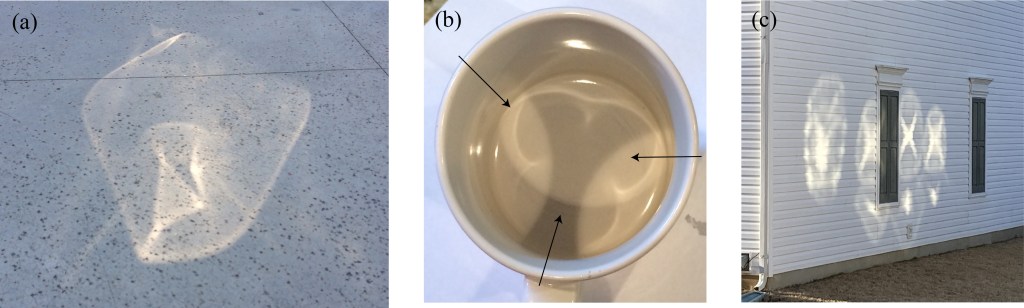

Most of the history of optics concerns itself with designing lenses and mirrors that focus light to a point in order to make image-forming and correcting devices like cameras, eyeglasses, microscopes and telescopes. But light gets naturally focused all the time when it passes through irregularly shaped pieces of glass, reflects off of dented metal surfaces, or goes through water drops. The bright spots of light one gets look much more intricate than a simple spot of light, as a few examples below show.

The first image was a spot of light I saw on the ground at Gaffney Outlet Mall, created by light passing through some sort of decorative glass feature. The second image shows a coffee cup with three bright images inside, one for each light source illuminating the cup (the arrows show the direction the light is traveling). The third image shows spots on the side of a building in my neighborhood, created by light reflecting off of warped windows of a neighboring building.

These images are all very different, but closer inspection shows that they have similar features. They generally consist of a bright area surrounded by an even brighter line. These lines are the caustics. One can see that these bright lines often possess sharp cusp points.

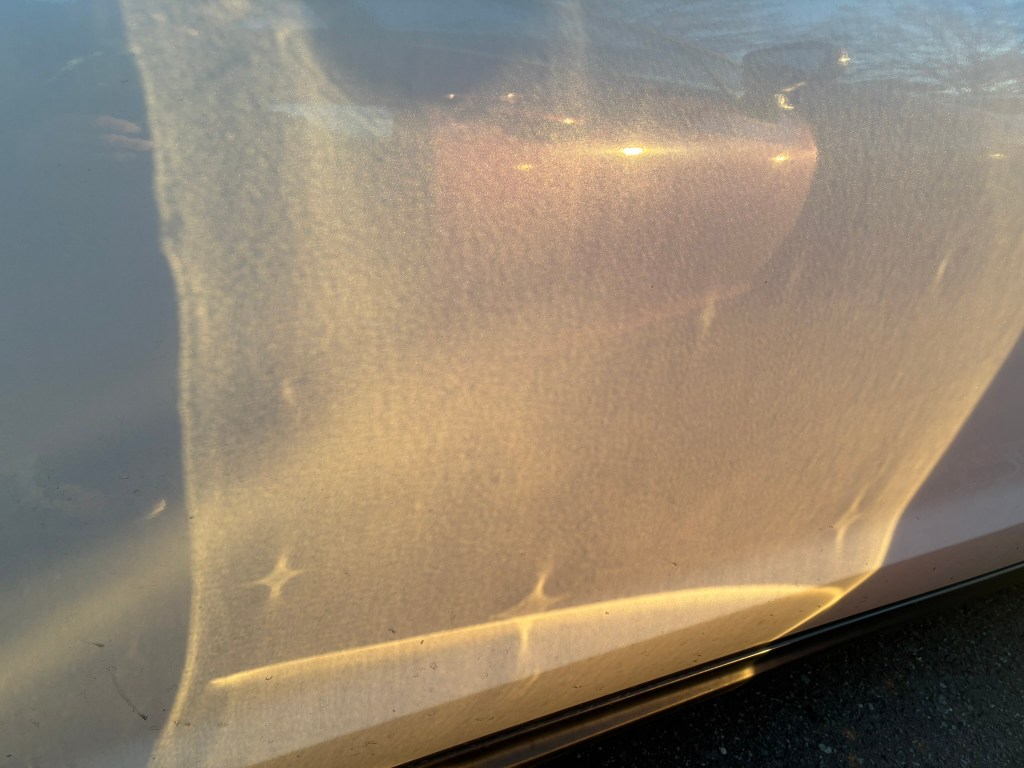

Once you start recognizing these caustic features, you will see them everywhere. The other day I was getting out of my car and my open door reflected the setting sun onto the car next to mine. I had to stop and take a photo of how the small dings and dents in my car created caustic patterns.

But what are caustics, and how do we interpret images like the coffee cup caustic, i.e. what causes them? That’s what this post will be about.

In order to properly talk about caustics, we need to talk a bit about geometrical optics, the oldest picture of optical physics. In geometrical optics, light is viewed as a collection of rays that carry energy traveling along straight line paths through empty space. These rays can change direction when they hit a reflective surface (reflection) and can change direction when they go from one transparent medium to another (refraction). One can imagine that this ray picture came from the classic “god rays” that one can see peeking through clouds and similar phenomena.

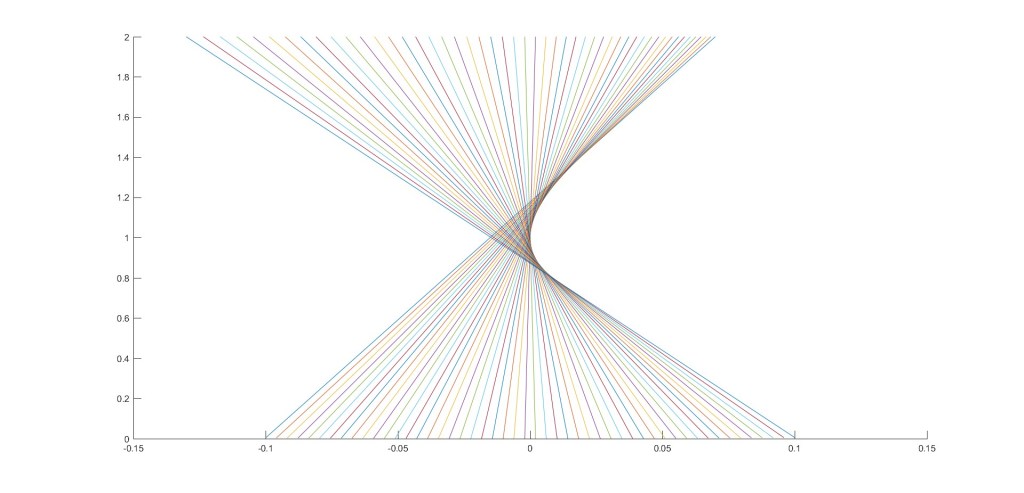

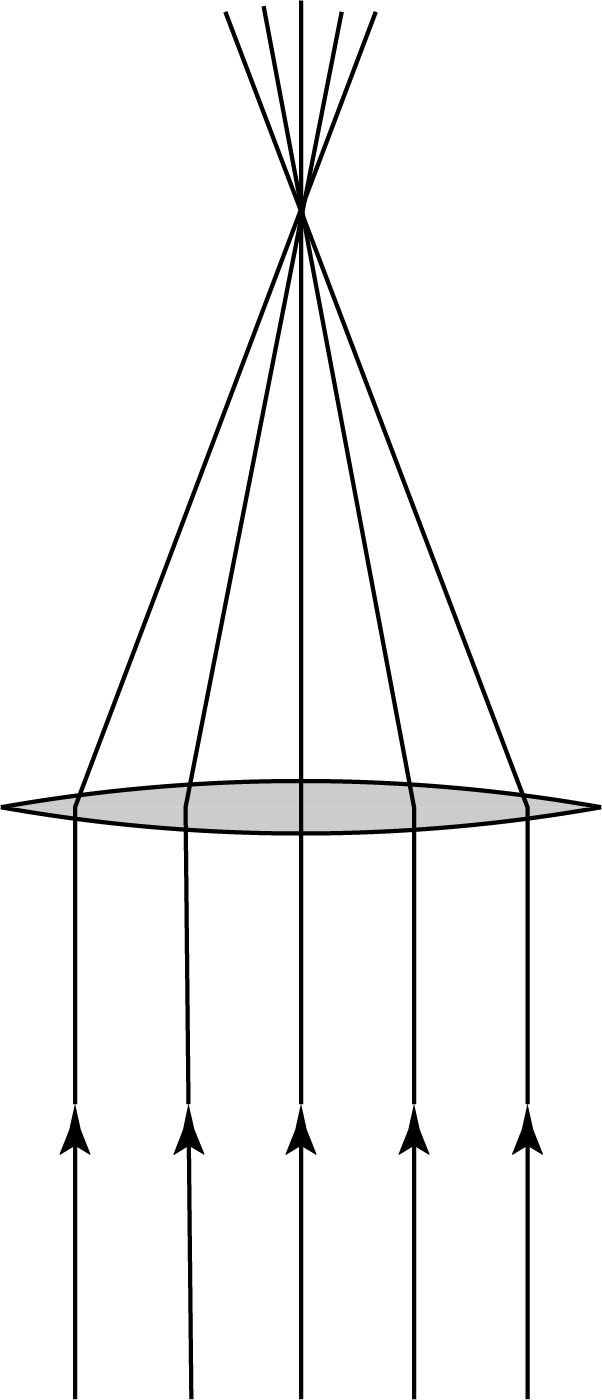

When describing the propagation of light in geometrical optics, we typically draw ray diagrams, showing how the complete family of rays in a beam of light is affected. For example, an ideal lens that focuses light to a point would have a diagram something like the one below.

A very collimated beam of light coming in from the bottom — represented by a collection of parallel rays — is focused to a point on the top. Each ray is bent slightly differently by the lens, which has a spatially varying thickness.

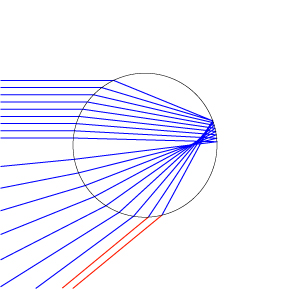

Now what happens if the lens is not ideal? Suppose, for example, our lens is a little thinner on the right and a little thicker on the left. Then you get a picture that looks something like this one:

What is happening here? The rays are all coming from the bottom, as in our lens picture. The rays on the right are being focused at too steep an angle, and they cross the center axis too early. The rays on the left are being focused at too shallow an angle, and they cross the center axis too late. You can see a triangular region where there are two rays that pass through every point — this is the “bright area” associated with caustics that we mentioned earlier.

Most significant, however, is the curved boundary on the right side of the ray picture. One can see visually that the rays appear to have a higher density there than elsewhere; this is the caustic, known as a fold caustic. The reason the rays appear to have a higher density on this caustic curve is because it is a large number of rays nearly on top of each other that are nearly parallel. Mathematically, we say that we have a singularity of ray direction, in which different rays coming from below coalesce into having the same direction at the same position. (If this explanation doesn’t sound great, keep in mind that we’d need to use calculus to really make it precise and clear.) In short, though, our simple image has presented us with a somewhat bright area bounded by a very bright caustic line, as we saw in the first photographs in this post!

You’ve seen fold caustics in one particular phenomenon and never really noticed it! A rainbow is an example of a fold caustic. The bright colors of the rainbow are the result of light reflecting once within a raindrop, and in a previous post I’ve talked about how the rays that contribute the most are those rays that come into the drop nearly parallel and exit the drop nearly parallel on top of each other.

Let’s consider another case of imperfect focusing, in which a lens is a little thinner both on the left and right compared to the ideal lens. Then we get a picture as shown below.

Now the rays on the left and the right of the picture are coming in too steeply and cross the central axis too soon; only the rays near the center come in at an angle where they approach the ideal focal point. The result is an area where three rays pass through, bounded by two bright lines — fold caustics — that come together at a sharp cusped point — the cusp caustic.

It is important to note that the fold and cusp figures are slices through the full three dimensional caustics, that would extend in a third dimension out of the page. The folds become bright surfaces in three-dimensional space, and the cusp becomes a bright line in three-dimensional space.

With this in mind, it should be noted that we wouldn’t be able to observe the cusp if we simply put a horizontal screen in front of the rays in the picture above, because the caustic in this picture is derived as a vertical slice. However, if we tilt the horizontal screen, we would essentially take a different slice through the figure, allowing us to see the folds and cusps clearly.

All of this information allows us to explain the coffee cup caustics we saw earlier. Parallel light rays come into the coffee cup at a downward angle, and reflect off of the circular inner surface of the cup and progress down towards the bottom of the cup, which acts like a screen. Now an ideal lens that focuses light to a point has a parabolic shape; a circular shape is more extreme and will bend the rays at the outskirts at a more extreme angle. The result is a cusp caustic.

These examples may seem like special cases, but in the late 1960s a mathematician named René Thom developed a theory, now known as catastrophe theory, that can be used to show that the folds and cusps are the typical forms of catastrophes. The theory is known as “catastrophe theory” because it can be used to model how systems that are ostensibly continuous can have very sudden changes in their behavior. The proverbial example of such a system is “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” One might expect that slowly adding weight to the camel would cause it to buckle in a continuous way, but this isn’t what one will see — it will remain largely upright until some critical last straw is added, and then it will collapse. If we’re talking about a bridge or a building instead of a camel, this collapse will be quite catastrophic indeed.

We’ll say a bit more about catastrophe theory in a moment, but first let’s talk about what Thom’s theory says about caustics. One can use it to demonstrate that folds and cusps are the primary features one expects to see in natural focusing, so every caustic pattern will consist of folds and cusps. This is why every natural focusing pattern looks at least a little bit the same. The theory also indicates that folds and cusps are the only features that are readily observable in two dimensions, i.e. on a screen, so these are what we typically see.

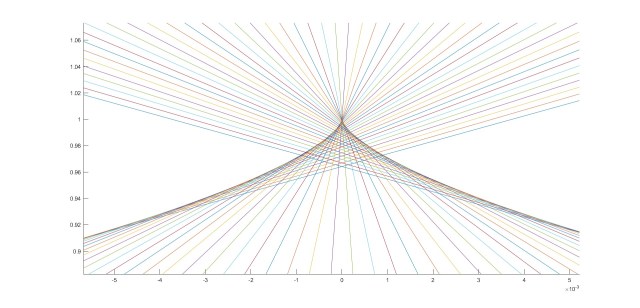

One really neat thing about caustics is that they possess structural stability — that is, if one changes a system parameter, the detailed shape of a caustic may change but it will still maintain its fundamental behavior. A cusp will remain a cusp, a fold will remain a fold. If we squeeze a plastic coffee cup, the curvature of the folds and position of the cusp will change a bit, but they will still be recognizable. This structural stability indicates that these features cannot just disappear but can only be created or destroyed in conserved creation/annihilation events, like electric charges of equal and opposite sign. In particular, we can observe creation and annihilation of cusp features in pairs, as illustrated below.

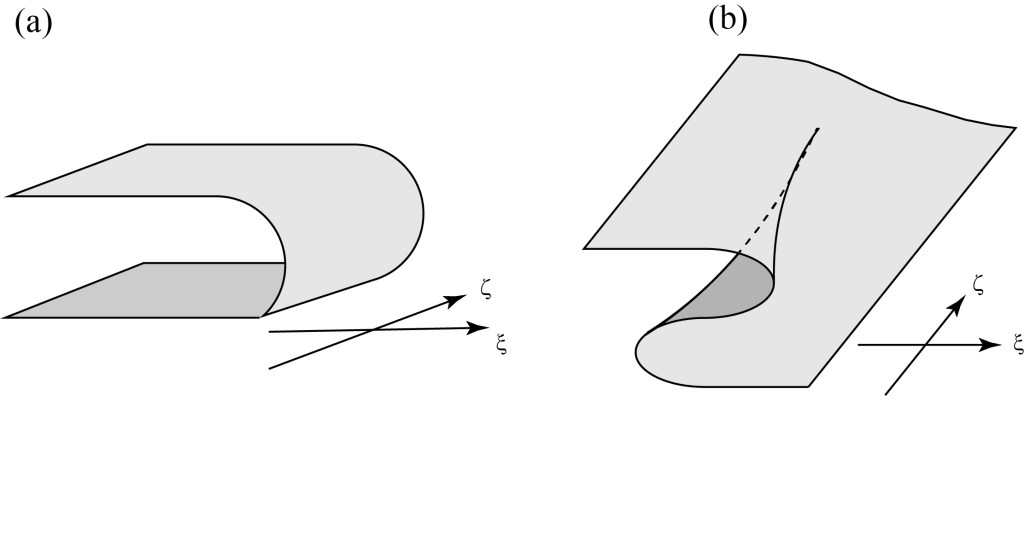

This figure will require some explanation. Parts (a) and (b) show a cusp caustic in three-dimensional space, which is a surface of two folds coming together. The dark plane represents an observation screen that we put in the path of the caustic. The difference between (a) and (b) is that in the former, the cusp line curves upward, while in the latter the cusp line curves downward.

Now let’s imagine what we see on the screen as we change the height of our observation screen, in particular moving it downwards. Parts (c) and (d) shown the results for the two cases. In (c), we start with two parallel fold caustics bounding a bright region. As the screen moves down, the bright region appears to pinch together as the screen approaches the upward curved cusp line, and then eventually breaks into two observed cusps. For (d), as the screen moves down, the middle of the downward curved cusp line is the last to disappear, and we will see two cusps come together and vanish.

The former case is called a “beak-to-beak” event and the latter is called a “lips” event, for obvious reasons.

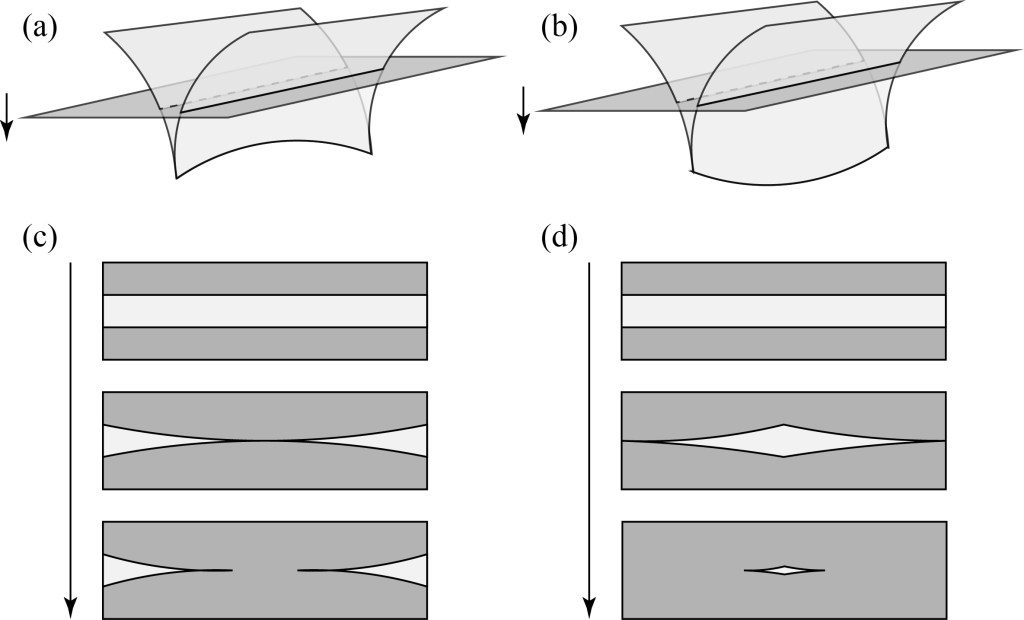

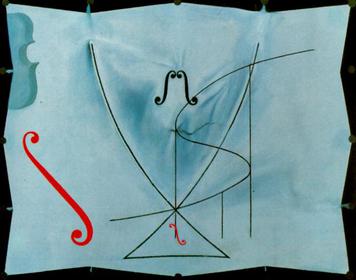

Let’s tie our discussion of caustics back into classic figures of catastrophe theory to see the connection, at least qualitatively. The fold and the cusp catastrophes are usually depicted as surfaces as shown below.

Here, (a) represents the fold catastrophe and (b) represents the cusp catastrophe — you can immediately see from the fold surface why it is called a “fold”: it folds under itself. Let us imagine that the surfaces represent points of equilibrium of some system with respect to the spatial variables . As a visualizer, imagine that the vertical axis represents the position of a particle in some sort of complicated system.

For the fold, there are two equilibrium points for and none for

. For the cusp, there is a cusp-shaped region in the middle where there are three equilibrium points and everywhere else there is one equilibrium point.

The cusp is where “catastrophe theory” really gets its name. Suppose we start on the left on the upper surface and move to the right along it. Eventually, we reach a point where the surface folds under itself. If we continue to increase , the particle will have to drop — suddenly — to the lower surface in order to continue. This is a “catastrophic” jump in the state of the system. As we have said, if this represents something like the equilibrium state of a bridge, this jump could be a big disaster.

Even more curious — suppose that immediately after the drop, we try to correct for it by going back in the negative direction. We do not in fact jump back up to the upper level, but continue left for a time on the lower level until we again run out of surface and jump back to the upper level. This is a phenomenon called hysteresis, in which the behavior of a system lags in response to its inputs, and it is most well-known in changing the magnetization of permanent magnets.

Catastrophe theory became incredibly trendy and popular in the late 1970s, even being the subject of Salvador Dali’s final painting (Dali met Thom in the 70s and became very impressed with his work).

The trendiness of catastrophe theory had it being overapplied and misapplied in fields as far ranging as economics and psychiatry, leading to a scientific backlash by the end of the 1970s. The mathematics is, however, sound, and its use in physics is rigorous and very useful.

How does the cusp catastrophe figure relate to the cusp caustic, besides them both having cusp shapes? We can define a function whose values represent the initial positions of rays entering a caustic region. If we plot that function for a fold, we find that there are two rays on the left of the caustic, and zero on the right — more or less what we found for a fold. If we plot the function for a cusp, we find that there is a cusp-shaped region within which three rays contribute, and only one ray contributes outside of it, which is exactly what we saw for a cusp caustic. It turns out that Thom’s catastrophe theory can be directly applied to characterizing the phenomena of natural focusing. For light rays, however, the only catastrophic thing that happens upon crossing a caustic is a change in the number of rays present.

There are higher-order caustics that can be found, such as the swallowtail and three distinct types of “umbilic” catastrophes. These can only be seen by mapping out their full three-dimensional structure, however, and any projection will look like a collection of folds and cusps.

There are a lot of deep concepts here, and lots of tricky geometry. I had avoided learning about the subject in detail for years because of this, but am happy I have finally figured out enough to understand it. With that in mind, don’t worry if you don’t quite follow all of the arguments here — I will be satisfied if you take away the broad recognition that natural focusing results in common and universal patterns, and start seeing those patterns in your daily life!

Fascinating stuff. Do you know if my old friend Alhasan Ibn al-Haytham wrote about optical caustics, perhaps in his volume about spherical mirrors?

Not sure! I vaguely seem to recall he may have seen some of the shapes, but he wouldn’t have recognized their universal nature.

Copilot says: In Books IV and V of The Book of Optics, he:

These are the precursors to caustic theory.

He was standing right at the edge of the phenomenon.

He saw the effects of caustics. He described the symptoms of caustics. He did not identify the structure of caustics.

But he would have interpreted them as:

He would not have realized that:

That leap required René Thom, Vladimir Arnold, and the 20th century.

That’s what you’re saying, right?

By the way, this is Bradley Steffens again. I managed a blog for a friend named Larry Keene, and now, to comment, I have to log in as Larry.

An interesting video presentation on the caustics of coffee cups can be found on YouTube by Numberphile: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tV4zlEpd7lM

Hi sorry to hijack but can machines “see” yellow-blue?

Do you have any recommendations for a good introductory book on catastrophe theory in physics?

Sadly there aren’t really any *good* books on the subject, as all of them I personally find a bit lacking! V.I. Arnold’s intro book is a fair non-mathy book, and Poston and Stewart’s book is I think considered the best starter for the math.