The history of science is filled with exaggerated and even untrue stories of scientists and experiments; there are a lot of people about (such as the Renaissance Mathematicus) who endeavor to debunk some of the more egregious myths out there, and the scientific hero worship that often comes with it. A good example is the infamous “death ray” of Archimedes, which has been shown quite conclusively to have been an impractical weapon.

Myths are often spread and propagated by people passing along imperfect information uncritically across generations. I am usually quite forgiving of such errors, but sometimes an article comes out that gets really under my skin and I need to go off on a rant.

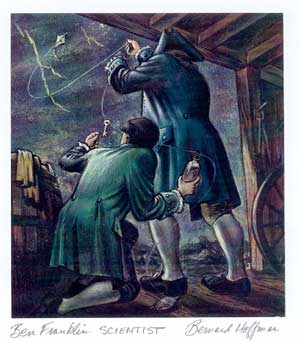

Case in point: the question of Benjamin Franklin’s famous flight of a kite in a thunderstorm! An article appeared on io9 the other day about “5 historical myths about real scientific discoveries,” which argues that Franklin never actually performed his experiment. The io9 article also references a Mythbusters’ episode, “Did Ben Franklin really discover electricity with kite and key?”

Both of these articles end up confusing the issue of Franklin’s kite experiment more than they clarify it. There seems to be an almost contrarian glee in suggesting that Franklin was, in fact, outright lying to the scientific community and, indeed, the world. I can’t speak with certain on what Franklin did or did not do, but I certainly can point out the flaws in the posted articles, which fail to make as strong a case as they think.

First, let me summarize the story of the Benjamin Franklin and the kite, which I have blogged about in much more detail in the past. Franklin’s interest in electricity was sparked* around 1746 when the Quaker merchant Peter Collinson sent an electrical tube to Franklin’s Library Company along with a regular shipment of books. The glass tube was essentially a friction rod: by rubbing it with silk, one could induce an electrical charge on it.

Franklin immediately set to work performing experiments with the tube, and by 1747 had produced enough results of note that he was suitably emboldened to send accounts of them to Collinson in England. Collinson in turn read the letters to the Royal Society, where he was a Fellow. The Royal Society at first in fact scoffed at Franklin’s investigations, and Collinson took the bold step of getting them published in pamphlet form. The set of pamphlets became immensely popular and were translated into French, and then Italian, German and Latin!

Two bold ideas came out of Franklin’s work. The first of these was the hypothesis that lightning is in fact a form of electricity. This was not necessarily a new idea, but Franklin bolstered it by providing a method to test it with his other innovation: the lightning rod. He had already observed that pointed metal rods could “draw off” electricity effectively, and he argued that a tall metal rod could draw off electricity from a thundercloud. He further suggested that such lightning rods could protect buildings from lightning strikes.

Illustration of d’Alibard’s experiment on May 10, 1752, demonstrating the sameness of electricity and lightning. From Louis Figurer, “Les Merveilles de la Science” (1867).

In May of 1752, Monsieur d’Alibard (one of Franklin’s admirers) erected a 40-foot iron rod in a French garden to test the “Philadelphia experiment.” When a thunderstorm passed, the rod became electrically charged, thus conclusively proving Franklin’s hypothesis and assuring his scientific fame.

Unaware of this experiment, however, Franklin had been endeavoring to prove his hypothesis on his own. The construction of a lightning rod had taken too long, however, and Franklin was unsure of whether it would be tall enough to draw down the “electric fire.” The thought then came to him to test his experiment with a kite in a thunderstorm, which would presumably draw down electricity. He apparently did this in June of 1752, and likely heard not long after about d’Alibard’s success. He delayed the formal announcement of his own experiment until October, though he published a notice of it in the Pennsylvania Gazette in August.

That’s the background; now let’s look at what the two articles I mentioned got wrong or misleading. We’ll start with the Mythbusters’ website:

Myth 1: Benjamin Franklin’s experiment was intended to “discover electricity.” No, no, no! Electricity had been observed for millennia before Franklin. Even the first systematic scientific observations go back at least to the work of William Gilbert in 1600. Franklin was attempting to confirm the equivalence of lightning and electricity, and it was a hypothesis that many were willing to bet on in that era.

Myth 2: Benjamin Franklin was trying to get his kite struck by lightning. Everyone in Franklin’s time knew about the inherent dangers of a powerful electrical bolt. Franklin himself, who had killed turkeys with even moderate electrical bolts, was certainly aware of the dangers of a direct lightning strike. His courage likely came from his original flawed belief that a lightning rod would protect a building by gently drawing the electricity from the air before it built to a deadly bolt. As he wrote to Collinson in 1750,

I am of opinion, that houses, ships, and even towns and churches may be effectually secured from the stroke of lightening by their means; for if, instead of the round balls of wood or metal, which are commonly placed on the tops of the weathercocks, vanes or spindles of churches, spires or masts, there should be put a rod of iron 8 or 10 feet in length, sharpen’d gradually to a point like a needle, and gilt to prevent rusting, or divided into a number of points, which would be better-the electrical fire would, I think be drawn out of a cloud silently, before it could come near enough to strike…

Emphasis mine. In fact, Franklin’s description of the kite experiment (again, given in more detail here) makes this clear:

As soon as any of the Thunder Clouds come over the Kite, the pointed Wire will draw the Electric Fire from them, and the Kite, with all the Twine, will be electrified, and the loose Filaments of the Twine will stand out every Way, and be attracted by an approaching Finger.

And when the Rain has wet the Kite and Twine, so that it can conduct the Electric Fire freely, you will find it stream out plentifully from the Key on the Approach of your Knuckle.

One might wonder where the idea of a direct lightning strike upon the key came from. It is possible it came from a misreading of Joseph Priestley’s 1767 account of Franklin’s experiment, where it is described as**:

Dr. Franklin, astonishing as it must have appeared, contrived actually to bring lightning from the heavens, by means of an electrical kite, which he raised when a storm of thunder was perceived to be coming on. This kite had a pointed wire fixed upon it, by which it drew the lightning from the clouds. This lightning descended by the hempen string, and was received by a key tied to the extremity of it…

Emphasis again mine. Here Priestley seems to be using “lightning” as a synonym for “electricity from the clouds.” It would not be a great leap for a later reader to misunderstand the description. We’ll hear more about Priestley in few moments.

So the Mythbusters conclusively showed that Benjamin Franklin would have been killed if his kite had been struck by lightning! That’s a valid myth to bust, but it is certainly not what Franklin himself, or his associates, ever implied.

Now let’s turn to some of the statements in the io9 article, which are also misleading but in a much more “touchy-feely” way.

Myth: Franklin didn’t provide a first-hand account of his experiment. I haven’t been able to find the original August 1752 Pennsylvania Gazette account of Franklin’s kite, but I have read the letter to Collinson, which is supposedly identical. The introduction reads:

As frequent Mention is made in the News Papers from Europe, of the Success of the Philadelphia Experiment for drawing the Electric Fire from Clouds by Means of pointed Rods of Iron erected on high Buildings, &c. it may be agreeable to the Curious to be inform’d, that the same Experiment has succeeded in Philadelphia, tho’ made in a different and more easy Manner, which any one may try, as follows.

Again, emphasis mine. He explicitly states that the experiment has succeeded! Though he did not speak much of the kite after this letter (more on this soon), Priestley’s account of the famous experiment begins with the following:

As every circumstance relating to so capital a discovery as this (the greatest perhaps, that has been made in the whole compass of philosophy, since the time of Sir Isaac Newton) cannot but give pleasure to all my readers, I shall endeavour to gratify them with the communication of a few particulars, which l have from the best authority.

The “best authority” in this case is most likely Franklin himself, as it is hard to imagine what else he means! Priestley did in fact had correspondence with Franklin about the history of electricity. No letter survives in which Franklin describes the experiment to Priestley, but it is extremely plausible that he did.

Myth: Franklin “gave only a basic outline of thunderstorm kite flying,” suggesting he never actually did it. This is a subjective statement, in my opinion. Franklin describes the kite in appreciable detail, and the level of detail seems no different than many of Franklin’s observations. For example:

Make a small Cross of two light Strips of Cedar, the Arms so long as to reach to the four Corners of a large thin Silk Handkerchief when extended; tie the Corners of the Handkerchief to the Extremities of the Cross, so you have the Body of a Kite; which being properly accommodated with a Tail, Loop and String, will rise in the Air, like those made of Paper; but this being of Silk is fitter to bear the Wet and Wind of a Thunder Gust without tearing.

To the Top of the upright Stick of the Cross is to be fixed a very sharp pointed Wire, rising a Foot or more above the Wood.

To the End of the Twine, next the Hand, is to be tied a silk Ribbon, and where the Twine and the silk join, a Key may be fastened.

This Kite is to be raised when a Thunder Gust appears to be coming on, and the Person who holds the String must stand within a Door, or Window, or under some Cover, so that the Silk Ribbon may not be wet; and Care must be taken that the Twine does not touch the Frame of the Door or Window.

Does Franklin’s letter seem rather brief? Keep in mind that he was not the first to demonstrate the sameness of electricity and lightning; d’Alibard had beaten Franklin to the punch. In light of this, Franklin may simply not have been that enthusiastic about publishing the results.

If the amount of details seem lacking, there may be a good reason for that, too. Returning to Priestley’s (and therefore Franklin’s) account,

it occurred to him, that, by means of a common kite, he could have a readier and better access to the regions of thunder than by any spire whatever. Preparing, therefore, a large silk handkerchief, and two cross sticks, of a proper length, on which to extend it, he took the opportunity of the first approaching thunder storm to take a walk into a field, in which there was a shed convenient for his purpose. But dreading the ridicule which too commonly attends unsuccessful attempts in science, he communicated his intended experiment to no body but his son, who assisted him in raising the kite.

The original kite experiment seems to have been a somewhat spur of the moment attempt that Franklin himself had doubts about. With this in mind, he may have taken a try at it without taking much care to record many details.

Argument: De Romas did the kite experiment in 1753, and his results differed from Franklin’s. This casts doubts on Franklin’s assertions. There is something funny about io9 mentioning the Mythbusters saying that a kite experiment is impossible in one paragraph, and citing De Romas’ successful experiment in the next!

On June 7th, 1753, Jacques De Romas*** indeed did raise an “electric kite” in front of a crowd of curious onlookers, and actually received a shock from the line so strong that it knocked him down! Franklin did not receive a similar shock, but there’s a very good and obvious reason for this: De Romas’ kite was outfitted with a copper wire! An earlier attempt by De Romas in May had failed, which De Romas had attributed to the low conductivity of the hemp kite wire. He therefore added highly conductive copper to his experiment, producing dramatic results. Franklin, on the other hand, was only using twine, and was clearly keeping the end he was holding dry.

Argument: Franklin didn’t argue the priority of the kite experiment with De Romas, suggesting that he never did it. De Romas appealed to the Paris Academy of Sciences to acknowledge himself as the first to perform the kite experiment, and Franklin did not respond to requests for evidence to the contrary.

De Romas’ June 7, 1753 demonstration of an electrical kite. Illustration from Louis Figurer, “Les Merveilles de la Science” (1867).

Why didn’t he respond? First of all, as we have suggested above, Franklin may have simply considered the experiment not important enough to quibble over. By 1753, Franklin was acknowledged throughout the world for his electrical discoveries, and the kite experiment was insignificant compared to his real achievements, including suggesting the original experiment that d’Alibard performed! Second, as we have also said, Franklin likely didn’t have any other documentation to provide other than the word of himself and his son. This doesn’t mean that he didn’t do perform the experiment.

Another reason is suggested by Franklin himself, in his own memoirs****, related to another argument with the French science community. When Franklin’s pamphlets on electricity appeared in France, their observations contradicted the works of one of the esteemed French scientists. As Franklin then notes,

The publication offended the Abbe Nollet, Preceptor in Natural Philosophy to the Royal Family, and an able experimenter, who had formed and published a theory of electricity, which then had the general vogue. He could not at first believe, that such a work came from America, and said it must have been fabricated by his enemies at Paris, to oppose his system. Afterwards, having been assured, that there really existed such a person as Franklin at Philadelphia, which he had doubted, he wrote and published a volume of Letters, chiefly addressed to me, defending his theory, and denying the verity of my experiments, and of the positions deduced from them.

Here you can already see Franklin’s characteristic wit at play! The most relevant part to our discussion follows,

I once purposed answering the Abbe, and actually began the answer; but, on consideration that my writings contained a description of experiments, which any one might repeat and verify, and, if not to be verified, could not be defended; or of observations offered as conjectures, and not delivered dogmatically, therefore not laying me under any obligation to defend them; and reflecting, that a dispute between two persons, written in different languages, might be lengthened greatly by mistranslations, and thence misconceptions of one another’s meaning, much of one of the Abbe’s letters being founded on an error in the translation, I concluded to let my papers shift for themselves; believing it was better to spend what time I could spare from public business in making new experiments, than in disputing about those already made.

Benjamin Franklin had taken the position that it was best to let his work speak for itself in his dispute with the Abbe; it seems eminently plausible to me that he did the same thing when, a few years later, the French science community again challenged his work.

*Takes deep breath* Okay, one more thing to address:

Myth: Franklin was playing a hoax on the scientific community to embarrass his French and English rivals. This is alluded to in the book “Bolt of Fate,” by Tommy Tucker, mentioned in the io9 post.

Franklin letters read at the Royal Society are marked with “disbelief and irony.” From Louis Figurer, “Les Merveilles de la Science” (1867).

It is certainly true that Franklin had some trouble with the French and English scientific communities, as I have mentioned above. Without having read Tucker’s book, several things seem rather problematic about the idea that Franklin was perpetuating a hoax that he later couldn’t admit to.

First, by the time he published his letters on the kite experiment in August and October of 1752, he was aware of the success of d’Alibard’s experiment proving Franklin’s hypothesis! He would also have been aware of how much this had raised his standing in the scientific community. A letter from the Abbe Mazeas to Dr. Stephen Hales describes events leading up to d’Alibard’s work and the high esteem Franklin’s research held even amongst the royalty:

The Philadelphian experiments, that Mr. Collinson, a member of the Royal Society, was so kind as to communicate to the public, having been universally admired in France, the king desired to see them performed. Wherefore the duke d’Ayen offered his majesty his country-house at St. Germain, where M. de Lor, professor of experimental philosophy, should put those of Philadelphia in execution. His majesty saw them with great satisfaction, and greatly applauded Messieurs Franklin and Collinson. These applauses of his majesty having excited in Messieurs de Buffon, d’Alibard, and de Lor, a desire of verifying the conjectures of Mr. Franklin, upon the analogy of thunder and electricity, they prepared themselves for making the experiment.

Second, we should note that, if Franklin’s kite experiment was a hoax, he actually perpetrated it directly via letter to Peter Collinson, who was by this time a good friend of Franklin’s, one of his most ardent supporters, and in fact the man who through a generous gift started Franklin on his electricity researches! One has to imagine Franklin possessing a sociopathic level of wickedness in order to ruin Collinson’s reputation to mock others.

Frontspiece to “The Life of Benjamin Franklin,” published in 1848. (Via the Smithsonian.)

Third, if we compare this supposed “hoax” of Franklin’s to others that he is known to have perpetrated, we find the kite “hoax” just isn’t very funny. Compare the kite tale to the “Enigmatical Prophecies” that appeared in Poor Richard’s Almanac in 1736. One prophecy of doom suggested that, “A great storm would cause all the major cities of North America to be under water.” A year later, Franklin revealed that rain storms had, in fact, placed all major cities literally under water! If the kite was supposed to be a mocking joke, it was uncharacteristically unfunny.

Finally, we should note that there is no direct evidence, anywhere, that Franklin made up his story. All of the evidence is of the form, “This seems odd…” or “Why didn’t he…”, and all of these things can be explained in more than one way.

So where do we stand? We will never be able to conclusively prove, one way or another, the truth of Franklin’s historic kite flight. He performed the experiment privately (with justification given above) and never repeated it. Arguments that the experiment was impossible are either based on a flawed understanding of what he was actually doing, or fail to note that another man, De Romas, performed a similar experiment successfully.

In the end, though, we are left with taking Franklin’s word on what happened. Given his status as a serious experimenter, and as an exceptional human being, I’ll take Franklin’s side until someone provides some sort of definite evidence to the contrary.

Painting of Benjamin Franklin flying a kite, by Bernard Hoffman. (Via ushistory.org)

******************

* See what I did there? Eh? Eh?

** I took the quotes from the 3rd edition of Priestley’s volume “The History and Present State of Electricity,” printed in 1775.

*** This is described by G. Berger and S.A. Amar, “The noteworthy involvement of Jacques De Romas in the experiments on the electric nature of lightning,” J. Electrostatics 67 (2009), 531-535.

**** Taken from “The Works of Benjamin Franklin,” J. Sparks, ed. (Hilliard, Gray and Company, Boston, 1840, Volume 1), p. 210.

Pingback: On Giants Shoulders #54: A Sleigh Load of History « Contagions

Thank you Thank you Thank you for this wonderful exegesis affirming Ben Franklin’s work with electricity and kites. A few weeks ago, someone posted to a Facebook group “American History” claiming to be a student in The Netherlands who had discovered a letter from Franklin’s son mentioning the experiment. As it turns out, the letter was a hoax deliberately manufactured by a university professor and a gleeful bunch of students:

http://www.lucthehague.nl/news/franklin-hoax.html

Regardless of their dissembling, I think we can expect that this hoax exercise – perpectuated in an academic setting – will be used by those who want to rewrite history, as a ruse to create doubt in legitimate period source documents. The same kind of people who now claim a “consensus” of doubt that Franklin ever flew the kite, are I suppose not happy with simply pretending real source documentation doesn’t exist and will use “experiments” like this to either discredit material that contradicts their pet thesis, or will try to poison legitimate archives by adding forged material of their own making. My apologies for ranting… my intent was to thank you for an excellent article that effectively refutes the iconoclasts in this case. 🙂

You’re very welcome! I get annoyed when I see folks spout on their pet theories (e.g. Franklin’s kite was a hoax) without even knowing the history — past of why I write this blog! 🙂

Pingback: Are you afraid ? | psykologist

Pingback: The Weather Research and Forecasting Innovation Act of 2017 – Charlie's Weather