Einstein’s special theory of relativity still is met with disbelief by a lot of non-physicists, and it is probably one of the most active areas of physics science denial out there. Write about relativity, and it is quite likely that you’ll get an angry commenter arguing that the entire theory is nonsense.

To be fair, it is extremely shocking and non-intuitive at first glance, as it forces us to reevaluate our notions of space, time, and simultaneity. In short: in response to a baffling inability to measure variations of the speed of light in vacuum with respect to relative motion, Einstein suggested that our laws of relative motion needed to be changed and he introduced two new postulates. The first postulate is that all the laws of physics are the same for every observer in acceleration-free motion. This was a big change from the Newtonian relativity picture, which said that the laws of kinematics (forces and motion) are the same for every observer, but not the laws of electromagnetism. The second postulate is that the speed of light is constant for every acceleration-free observer, regardless of the motion of the source or the observer.

This second postulate is the one that directly leads to some of the most bizarre consequences for physics. In order for observers to agree on the speed of light regardless of their relative motion, they must disagree on the length of moving objects (length contraction) and on the clock rate of moving objects (time dilation). Furthermore, the speed of light, c = 300,000,000 meters per second, ends up being an absolute speed limit that nothing can beat. Objects with mass always move slower than the speed of light, and light itself moves at c (though that is a bit of an oversimplified statement). Perhaps the strangest consequence of special relativity is the relativity of simultaneity: observers in relative motion will disagree about whether spatially separated events happen at the same time or not. Time and space cannot be considered separate independent quantities, and instead we must think about a unified spacetime.

These effects typically become significant only at speeds comparable to the speed of light, so in our day to day activities we don’t experience them. This is why relativistic effects are so perplexing at a first look: they conflict directly with our intuition.

Nevertheless, physicists are quite confident in special relativity, because it has been tested experimentally in many, many different ways since Einstein first introduced it in 1905. Some of these are so common that they hardly classify as “experiments” anymore! For example, high energy particle colliders like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN know how fast their particles are moving, and they’re always moving slower than c and in accordance with special relativity. Unstable muon particles that are created in the upper atmosphere can be detected at ground level because of time dilation: their average rate of decay is slower because of their high speed.

I’ve been looking into some of the actual laboratory experiments to test special relativity recently, and thought I would share a very elegant one that tests time dilation. Titled, “Measurement of the Red Shift in an Accelerated System Using the Mössbauer Effect in Fe57“, it is work done in 1960 by researchers at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, England1. It is a relatively simple and straightforward test, so let’s take a look!

To understand the paper, we need to talk a bit about another effect in special relativity: the relativistic Doppler effect. The term “Doppler effect” refers to the perceived change of frequency of a wave emitted by or detected by a moving object. All of us have experience the Doppler effect at some point in our lives: if you’ve ever heard the horn of a passing train, which seems to go from a high pitch to a low pitch as the train passes, that’s the Doppler effect. In fact, the first experimental test of the Doppler effect was done in 1845 using trumpeters on a train, organized by Dutch scientist C. H. D. Buys Ballot; listeners with perfect pitch were stationed by the side of the train to listen for the change in frequency.

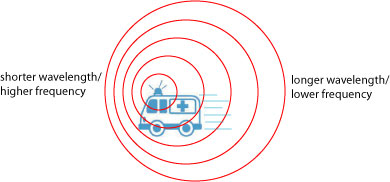

We can understand the Doppler effect with the image below, showing sound waves emanating from the siren of a speeding ambulance. The spacing between the wave peaks, the wavelength, is smaller in front of the ambulance, because the ambulance is moving towards the emitted waves; the spacing is larger behind the ambulance, because the ambulance is moving away from the emitted waves.

An analogous thing happens for light waves emitted from a moving source or received by a moving detector; we refer to a redshift if the detector is moving away from the light, and a blueshift if the detector is moving towards the light. The strange nature of relativity makes the behavior of the Doppler shift for light significantly different than that for sound, however. At the moment a train passes right next to you, the pitch of its horn sounds normal: at that moment, the train is not moving towards you or away from you. As a source of light passes you, however, or you pass a source of light, its frequency is still different than that of a stationary source, because of time dilation. This is referred to as a transverse Doppler shift, and it is in essence a direct test of relativistic time dilation.

The simplest analysis of the problem can be done from the perspective of the source. The source sees clocks running slow at the detector, which means that the detector will see a higher frequency of light — a blueshift!

This is the prediction that the English researchers hoped to confirm. As a source of electromagnetic radiation, they used gamma rays (high-energy photons) emitted by a Co57 (cobalt-57) radioactive sample.

In order to detect such a transverse Doppler shift, one needs fast transverse relative motion between source and detector. They opted to put the source on the central axis of a rapidly rotating cylinder, as illustrated below; the cylinder could be ramped up to 500 revolutions per second at its fastest.

The cobalt source is on axis, and sandwiched between two dural (aluminum alloy) plates. A cylindrical shell of lucite lies between the dural plates, coated with an Fe57 (iron-57) film. A lead shield collimates the outgoing gamma rays by blocking those that don’t pass right to the detector, which is a counter that simply counts how many gamma rays per second are detected.

At first glance, you might wonder how relativity comes into this situation at all, as the counter and the source are stationary relative to each other! The key is the fast motion of the iron film and an effect known as the Mössbauer effect.

Often, when we think of the absorption of photons, we imagine a single photon being absorbed by a single atom, and the momentum of that photon being taken up by the atom, in what is called the recoil. In a crystalline structure, however, all the atoms are bound together in a crystal lattice, and the recoil can be taken up by the entire lattice. Because the lattice as a whole is much, much heavier than a single atom, the effect is essentially recoilless.

I will return to the Mössbauer effect in a future post, because it is fascinating. The important feature for our purpose is that the lattice only absorbs photons over a very, very small range of frequencies (or energies). In a situation where the cobalt and the iron are stationary with respect to each other, the gamma rays emitted by the cobalt are resonantly absorbed by the iron, and there is almost no transmission.

When the experiment is rotated, however, the gamma rays experience the transverse Doppler effect! From the perspective of the iron, the gamma rays are arriving with a higher frequency. The faster the experiment is rotated, the higher the frequency of the gamma rays, and the further their frequency is away from the absorption resonance of the iron.

The result is that, as the experiment is rotated faster, the gamma rays will be absorbed less. From the transverse Doppler effect, it is predicted that the number of gamma rays detected should increase quadratically as the rotation speed is increased. And this is exactly what was detected!

The experiment can be viewed as a direct test of time dilation in special relativity, through the transverse Doppler effect. Alternatively, it can be viewed as a test of general relativity, in which accelerated systems are locally equivalent to a gravitational field! In this case, the rotation is the acceleration; the frequency shift of the gamma rays represents the increase of energy of a photon in falling into a gravitational well. This latter view is what the experimenters were testing, but it appears the experiment is remembered more for its time dilation interpretation.

Curiously, the paper title refers to the “red shift” of the system, though my understanding is that the photon is effectively blue shifted! If one interprets the experiment from the point of view of the iron film instead of the source, I believe you can view the photon as experiencing a red shift due to time dilation, but a stronger blue shift due to length contraction, resulting in an overall blue shift. This may be what the researchers had in mind, or they may have simply misunderstood the direction of the shift. The experimental results would look basically the same for a red shift or a blue shift, both of which would involve the gamma ray shifting away from resonance.

This is just one of many experimental tests of the strangeness of relativity! I will talk about others in future posts.

**************************************

- H. J. Hay, J. P. Schiffer, T. E. Cranshaw, and P. A. Egelstaff, “Measurement of the Red Shift in an Accelerated System Using the Mössbauer Effect in Fe57“, Phys. Rev. Lett. 4 (1960), 165.

Another early example of using recoilless nuclear resonance fluorescence in “Iron-57” to detect a relativistic effect was applied to that of Earth’s gravity in Pound and Rebka’s, “Gravitational Red-Shift in Nuclear Resonance”, published in 1959.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.3.439

I must just have had a good instructor. Relativity was one of the few topics that seemed to make both logical and intuitive sense to me. But it was also presented as the logical result of conserving “causality”, or more specifically, chronological order and relative energy between events at interconnected points in spacetime.

Nice! I’ll have to take a look.

//Write about relativity, and it is quite likely that you’ll get an angry commenter arguing that the entire theory is nonsense.//

I agree.