The special theory of relativity has been extensively tested ever since Albert Einstein formulated it in 1905, and is essential in understanding numerous fields of physics, from astrophysics to nuclear physics to particle physics. Recently, I’ve been exploring some of these experimental tests, like the 1960 laboratory test of time dilation.

What surprised me, however, was learning about a 1901 experiment that provided evidence of special relativity before Einstein introduced it! Most physicists are familiar with the 1887 Michelson-Morley experiment that failed to find any variation of the speed of light and really spurred a lot of the work on relativity theory, but this 1901 research is something that one doesn’t see in textbooks.

So, of course, I had to translate the paper, which is in German, and write a blog post about it! For those who want to read my translation, the pdf is here; the original in German can be read on Wikisource. The paper is by Walter Kaufmann, and has the translated title, “The magnetic and electrical deflectability of the Bequerel rays and the apparent mass of the electrons.” It appeared in Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen – Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse of the year 1901, page 143-155.

Let us begin our discussion with Einstein’s theory of special relativity as we currently understand it, highlighting the parts most relevant for our understanding of the 1901 experiment. The concept of “relativity” predates Einstein, and is in fact one of the earliest principles in physics. It may be summarized by the statement that only relative motion between bodies is detectable, and that there is no sense of absolute motion. The idea can be traced back to Galileo, who noted that a person in the depths of a ship moving on calm waters would be unable to detect their motion by any experiments in the ship, and they would get the same experimental results as someone sitting in a ship stationary in port.

Relativity can be formulated more specifically as the idea that the laws of physics should appear the same to anyone moving in constant relative motion with respect to each other. But which laws of physics? For Galileo and Newton, it was the laws of motion and forces. But Galilean relativity predicts that different observers can measure different values for the speed of light, based on their motion. Someone moving towards an approaching beam of light will measure a faster speed of light than someone moving away from an approaching beam of light. This hypothetical variation of the speed of light was exactly what Michelson and Morley attempted and failed to find in 1887.

Einstein revised and expanded the concept of relativity to include the laws of electricity, magnetism, and light; in short, regardless of relative motion, everyone should agree on the value of the speed of light, even people in relative motion measuring the speed of the same beam of light! The only way this works is if the different observers have different measures of length and time. This leads to the idea that there is no “absolute” measure of time, and that time and space are fundamentally intermingled as a structure we call spacetime.

This expanded form of relativity leads to a lot of surprising effects that we’ve discussed before, like length contraction and time dilation. But it also leads to changes in the definitions of the energy and momentum of particles with mass, which is what we will be concerned with here.

Let’s start with momentum, which I often roughly describe as how much “oomph!” a moving object has. In the classic Newtonian description of dynamics, momentum is defined as the mass of the object times its velocity.

This definition makes intuitive sense: a truck tends to have more “oomph!” than a car with smaller mass moving at the same speed, and a faster-moving truck has more “oomph!” than a slower-moving truck.

Newton’s formula works just fine for objects moving much slower than the speed of light, which includes pretty much everything we observe in everyday life, including planets! When things are moving at speeds comparable to the speed of light, however, the correct formula is of the form

Here, “Gamma,” the Greek letter γ, represents the mathematical quantity

,

where v is the velocity and c is the speed of light. The factor γ goes to infinity as v approaches c; one consequence of this is that it is impossible (as far as we know) for an object with mass to reach the speed of light, as it would require an infinite amount of force to impart the infinite momentum of such an object.

(Incidentally, when v is small compared to c, γ =1 and the Einstein formula reduces to the Newton formula. Special relativity therefore treats Newtonian relativity as a slow speed special case.)

There is a curious way to interpret the Einstein momentum formula. Since it looks almost the same at the Newton formula, one can group together the product of gamma and mass and say that, at relativistic speeds, the mass of an object increases. In other words, we can write

We therefore argue that the Newtonian momentum formula is unchanged at high speeds, but the mass of the particle increases. Most physicists, including Einstein, do not consider relativistic mass a proper way to look at the problem, and instead say the mass is unchanged but the formula for momentum is different from the Newton version at high speeds. But anyone doing an experiment where they measure the mass or momentum of a moving particle could just as easily interpret the results in terms of Newtonian momentum and a changing mass!

This brings us at last to the 1901 paper by Kaufmann! In the years leading up to it, weird and wonderful discoveries had been made in physics that had opened new avenues of research previously unimagined. Of particular interest to our discussion was the official discovery of the electron, the negatively-charged building block of nature, in 1897 by British physicist J.J. Thomson.

Looking back, it can be hard to appreciate what a big impact the electron had on physics, but it was the first truly “fundamental” particle discovered. Electricity had long been treated as a pair of ideal fluids, one positively charged and one negatively charged, and though atoms are a building block of nature they had already been found in such a wide variety of species that they could hardly be considered fundamental. With the discovery of the electron, suddenly physicists had a metaphorical grip on something connected to the very foundations of physics, and they scrambled to learn everything about it that they could.

Particularly strange results were predicted when the concept of an electron was combined with the existing understanding of electromagnetism. Thanks to James Clerk Maxwell, researchers had known since the 1860s that light is an electromagnetic wave. In analogy with known waves like water waves and sound waves, it was expected that light must propagate through some as yet undiscovered material medium. Water waves are oscillations in the water, while sound waves are oscillations in the air; for light, a hypothetical medium called the aether was introduced as the carrier of electromagnetic waves. It was so named because no such medium had ever been observed; it was “etherial.”

But if the aether is the carrier of electromagnetic waves, then it must also interact with electric charges such as the electron. In 1881, electron-discoverer J.J. Thomson calculated1 what would happen if a charged particle like an electron moved through a medium that it interacts with, like the aether. He noted that a moving charged particle would induce currents in the medium, and these currents would carry energy; the faster the particle moved, the more energy would be carried along with it in the medium. In short, the particle would appear to gain mass2 the faster it moved!

Over the next couple of decades, other researchers would make similar calculations with different assumptions about the electron and the medium it was passing through, arriving at different mathematical forms for this mass gain.3

Which formula was correct, and what did it tell us about the electron and the aether? The natural way to answer this question was by running an experiment, and this is what Kaufmann did.

The first challenge in the experiment was to find a sufficiently fast-moving source of electrons. Most experiments on electrons used cathode ray tubes to generate them; “cathode rays” was the name for the mysterious stream of electric charge that emanated from the cathode in an evacuated tube and arrived at the anode. Experiments with cathode ray tubes had been the means by which Thomson confirmed the existence of the electron (and which I should blog about, too).

Existing cathode ray tubes, however, produced electrons moving at 1/5 to 1/3 of the speed of light, and although those speeds seem fast on a terrestrial scale, theoretical calculations indicated that they were still too slow to show any appreciable mass change.

But another source of extremely fast-moving electrons had been recently discovered! In 1896, Henri Becquerel accidentally discovered the phenomenon of radioactivity, and quickly determined that there were three types of radioactive emissions: electrically positive, electrically negative, and electrically neutral. Researchers would later determine that these were helium nuclei, electrons (or positrons), and high-energy photons. The emitted electrons had already been found to move almost at the speed of light, so they would make an ideal test subject for mass changes.

The other experimental challenge was determining the mass and velocity of the emitted electrons. Here, existing methods would work well. An electron passing through an electric field experiences a force in the direction of the field; a faster-moving electron spends less time in the field and is deflected less. An electron passing through a magnetic field experiences a force proportional to its velocity, and perpendicular to both the field direction and the velocity of the electron. An electron passing through an electric and magnetic field simultaneously will experience deflections in two perpendicular directions due to the two fields. Because the acceleration of a particle depends on its mass, the measured deflections can be used to determine the mass and velocity of the electron, assuming its charge is known and constant.

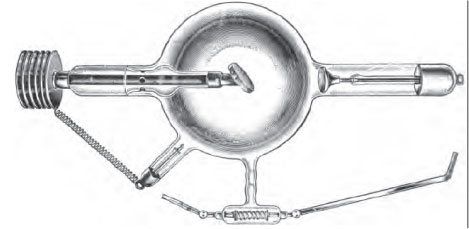

This, in essence, is what Kauffman did, and his experimental sketch is shown below. A radioactive source, a tiny grain of radium bromide, was deposited at the point C. The emitted electrons passed through an electric field produced by charged capacitor plates P1 and P2, and a magnetic field produced by an electromagnetic with poles N and S. The electrons would be emitted in all directions, so a diaphragm D was used to create a directional beam by blocking any not passing through the hole. A photographic plate at E recorded the impact of the electrons.

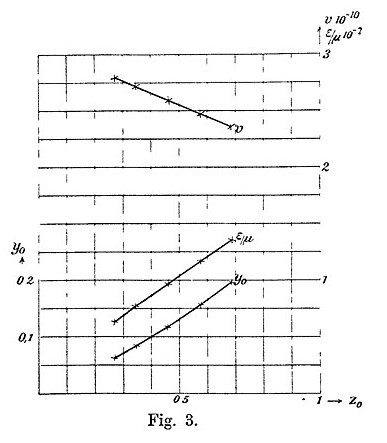

Kaufmann’s “raw” experimental results are shown below; electrons are emitted with a range of speeds, resulting in a line of measured data. The figure shows, in essence, the same data in three different forms. The first form shows the measured positions of the electrons as deflected along the y0 and z0 directions by the electric and magnetic fields, respectively, and is closest to what would have been recorded on the photographic plate. The second form shows how the velocity of the electrons depends on the z0 position. The third form shows how the charge/mass ratio depends upon z0.

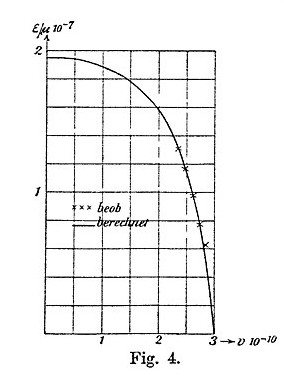

Kaufmann then performed his own mathematical analysis, determining the relationship between the speed of the electrons and their charge/mass ratio. His plotted results are shown below.

One can see that, as the speed approaches the speed of light (which is approximately 30 billion centimeters per second on the right edge of the figure), the ratio of charge to mass drops rapidly, evidently approaching zero, which means that the effective mass becomes infinite!

This was the first experimental measurement of “relativistic mass,” though Kaufmann did not realize it at the time. Kaufmann instead used electron calculations by George Searle to estimate, based on a specific model of the structure of the electron, how much of the electron’s mass was “real” and how much was “apparent” and due to the interaction of the electron with the aether.

For such a significant result, it might seem surprising that Kaufmann’s experiment doesn’t get more attention. This is probably Kaufmann’s own fault: in 1905, with special relativity now unveiled and several competing theories of effective mass on hand, Kaufmann repeated his experiment and concluded that his results agreed with an aether interpretation and contradicted Einstein. The famed physicist Max Planck reinterpreted Kaufmann’s data, however, and found that Kaufmann’s results contained analysis errors and furthermore were not precise enough to properly confirm one theory or another! Everyone agreed that Kaufmann had showed that there is an apparent mass increase for fast-moving electrons, but his results did not really answer any of the important questions relating to electron mass and motion.

Other researchers performed more refined versions of Kaufmann’s experiment, but it wasn’t until 1940 that experiments showed quite conclusively that the formula predicted by Einstein’s relativity fit the data best.

I really loved learning about Kaufmann’s experiments for two reasons. First, it is always fascinating to see evidence for a particular scientific theory, in this case special relativity, discovered before the theory itself is formulated!

Second, diving into the studies of electron motion pre-Einstein gives me a greater appreciation for Einstein’s discovery. As I’ve noted before, some scientists have argued in the past (and some still probably do) that the important work of special relativity was the mathematics done by Lorentz and Poincaré before 1905, and that Einstein made a relatively small contribution that was overhyped.

Looking at the electron theories pre-Einstein, however, one sees what a confusing mess it all was! In order to explain the motion of the electron, one needed to have a model for the structure of the electron as well as a model for the aether and how it responded to electric charges. This resulted in a variety of competing theories, each of which had quite complicated formulas for the electron mass. For example, Searles’ formula looked as follows:

,

where e is the electron charge, a is its radius, and , the ratio of the electron speed to the speed of light. In Einstein’s special relativity, the “relativistic mass” follows a much simpler relationship, and does not depend at all on the structure of the particle.

In one fell stroke, Einstein rendered unnecessary a large and confusing body of literature, while opening up physics to a new field of amazing discoveries. Kaufmann’s experiments were just a hint of the wonders to come.

****************************************************

- Thomson, Joseph John (1881). “On the Electric and Magnetic Effects produced by the Motion of Electrified Bodies” . Philosophical Magazine. 5. Vol. 11, no. 68. pp. 229–249.

- For any relativity deniers out there: the mass change calculated by Thomson and others due to a hypothetical aether ended up being quantitatively different from the result predicted by special relativity. Experiments have validated the relativity formula.

- Furthermore, in a demonstration that scientific history often rhymes, researchers speculated that all the mass of the electron might arise from its interaction with the aether. This is strikingly analogous to modern particle physics explanations of mass, which propose that particles gain mass through interaction with the “Higgs field” that permeates all space. Again, let me stress that the “devil is in the details” here: the quantitative results for the Higgs field are very different from the early aether theories.