When we are taught the history of physics, it is quite common for major discoveries to be introduced in an abbreviated form that loses much of the very interesting context. We are told “Scientist X discovered Y in year XXXX,” but are often not told about the tortured path of investigations that lead up to Y and the numerous questions that were answered by the new discovery.

A great example of this is the discovery of the electron! The electron was officially discovered in 1897 by British physicist J.J. Thomson using experiments on cathode rays (mysterious “rays” emanating from the cathode in a vacuum tube), in which he was able to estimate both the mass and the charge of electrons. That description is quite abridged, however, and there was a long philosophical discussion about the existence of electrons preceding its discovery and a lot of mysteries that were suddenly unraveled by its existence.

I was thinking about this a lot recently due to two factors. The first is that I wrote a blog post on an early inadvertent test of special relativity investigating the apparent mass of electrons. That paper by Kaufmann gave me a sense of how radical the discovery of the electron was at the time and how eager people were to determine all of its properties. The second factor was… a mistake? Kaufmann’s relativity paper came out in 1901, and was in German, and was about electrons; my first attempt to track it down led me to a 1901 paper by Kaufmann in German about electrons, and I started translating it. About halfway through translation, I realized that the paper was not the one I was looking for, but it was so interesting that I finished translating it anyway!

The paper in question was a public lecture that Walter Kaufmann wrote on “The development of the concept of electrons,” and it is a timely overview of the history of the concept and everything that had been learned since its formal discovery! It is such an interesting read I thought I would share my translation in its entirety in this blog post, with my own annotations and explanations to provide context when needed.

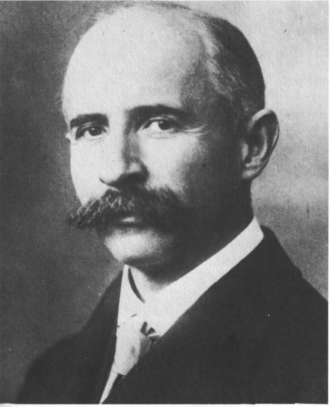

First, let’s say a few brief words about the author of the paper. Walter Kaufmann (1871-1947) was a German physicist who studied physics at the Universities of Berlin and Munich, receiving his doctorate in 1894. He became habilitated (qualified for a teaching position) in 1899, and became a Professor of Physics at the University of Bonn. Considering that the discovery of the electron occurred in 1897, Kaufmann was naturally positioned to investigate the properties of this strange new particle.

So let’s get cracking on Kaufmann’s lecture!

Gentlemen! It is not an uncommon phenomenon in the history of science that views long considered obsolete and surprising suddenly regain authority, albeit in a more or less modified form. An extremely interesting example of this phenomenon is offered by the revolution in our views of electrical processes which has taken place in the course of the last decade and which I have the honor of reporting on today.

In this introduction, Kaufmann already hits upon an important point: people had been speculating on the existence of a fundamental electric particle for a long time.

The modern theory of electrical phenomena and the optical phenomena closely linked to it, which can be summed up under the name of electron theory, means a return to views as expressed by Wilhelm Weber and von Zöllner in the 1860s and 1870s — modified by the results of Maxwell’s and Hertz’ research. W. Weber understood electrical phenomena as the effect of elementary electrical particles, so-called electrical atoms, whose mutual influence depended not only on their position but also on their relative speeds and accelerations.

Here we learn of a couple of interesting names. Wilhelm Weber, a German physicist whose work will be discussed in a moment, was the co-inventor of the first electric telegraph with Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1833, and also an early advocate for the idea that electricity was carried by particles. At the time, the conventional thinking was that electricity consisted of two continuous “fluids,” one positive and one negative. Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner was a German astrophysicist who made the first measurement of the brightness of the Sun in 1867. He was also fond of optical illusions, and discovered the Zöllner illusion where parallel lines appear to be not parallel.

Like many physicists of that era, Zöllner became a psychic investigator late in life, and like many physicists of that era, he was completely conned by a number of fake psychics.

It is a bit hard to track down the details, but it appears that Zöllner also introduced an “electrical atom” model as part of an attempt to explain why comets have tails in his 1872 book Ueber die Natur der Cometen. I will have more to say about this in the near future.

Neither Weber’s work nor Zöllner’s took into account the work of James Clerk Maxwell, who published his “A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field” in 1865 and showed how electricity, magnetism, and light are related and that light is an electromagnetic wave. This latter hypothesis was later verified by Heinrich Hertz in 1888, who experimentally generated radio waves using an electrical apparatus.

Let’s return to Kaufmann:

Even if Weber succeeded in using his assumption to completely describe the electrodynamic processes known at the time and even to give a qualitatively very useful explanation for the proportionality between electrical and heat conduction in metals, as well as for the Ampère molecular currents in magnets, his theory was far from becoming the common view of the physicists of the time. The reason for this negative success may well be found in the fact that most of the laws of electrodynamics, expressed purely phenomenologically in the form of differential equations, proved to be much more convenient and simpler than Weber’s formulas.

One of the big puzzles in the era prior to the discovery of electrons came from recognizing that metals seem to conduct heat and electricity very well, and that heat conduction and electrical conduction go hand-in-hand. We now know that electrons are connected to both: heat is a random thermal excitation of electrons, and electrical currents are a flow of electrons. In metals, many electrons are only weakly bound, and are free to move about, allowing for a rapid flow of both heat and electricity.

Weber used his crude electron theory to demonstrate this relationship, but as Kaufmann notes, Maxwell’s equations did not seem to need the assumption of an electron, and Maxwell’s equations were so simple and useful that researchers focused on them.

In addition, Weber made no attempt to calculate the size of the electric atoms he assumed and to check the result of the calculation by applying it to other molecular processes. Finally, however, it was added that, on the basis of the work of Faraday and Maxwell, one finally came to the general conviction that, in the case of electrical and magnetic processes, a temporal propagation had to take the place of the direct long-distance effect, a requirement that Gauss made in a letter to Weber as early as 1845, but which was not fulfilled by Weber’s law. Maxwell’s treatises, written in 1861-62, which he then summarized in his famous “Textbook of Electricity and Magnetism” in 1873, as well as the brilliant experimental confirmation of Maxwell’s results by H. Hertz from 1887 onwards, seemed suitable for the Weber’s views to take even the last remnant of raison d’être.

Obviously, if one proposes a new particle, one should attempt to determine its elementary properties, such as mass and size (though these days we believe that the electron is a true point particle). The final point that Kaufmann makes is a significant one. Early theories of electricity and magnetism focused primarily on “static” problems, in which nothing changes in time, and in those theories it was assumed that electric and magnetic forces acted instantaneously, in what was called “action at a distance.” Maxwell’s theory, however, demonstrated that all electric and magnetic disturbances travel at the speed of light, the “temporal propagation” mentioned above. Weber’s theory could not account for this, which also made it weak in the eyes of researchers.

In fact, Maxwell’s formulas, which lack any atomistic concepts at all, represented the fundamental electrical phenomena just as well as the older ones based on action at a distance, and the newly discovered Hertzian electric waves could only be represented by Maxwell’s theory.

In short, Maxwell’s equations seemed to explain almost everything related to electricity and magnetism that was known, so it seemed that Weber’s theory was unnecessary. It was probably reasonable to assume that the mysterious electrical/heat conduction problem would be explained in the context of Maxwell’s equations eventually as well.

It seems as if this brilliant success initially blinded the investigators to the inadequacy of Maxwell’s theory with regard to finer optical phenomena. According to Maxwell, the light oscillations should not be mechanical oscillations of the ether, but electrical oscillations, and the two constants that Maxwell used to define the electrical and magnetic behavior of every body (the dielectric constant and the magnetization constant) also had to be decisive for its light refractive power. Even if the relationship demanded by Maxwell – namely that the optical refractive index should be equal to the square root of the dielectric constant – was reasonably fulfilled for some bodies, on the other hand many bodies, e.g. water, showed such enormous deviations that the theory was based on this alone had to prove insufficient in its original form. Added to this was the dependence of the refraction exponent on the colour, for which the original theory gave no explanation at all.

Here we get into some interesting details. Maxwell had connected the refractive index of light in matter, usually labeled n, to the (normalized) electrical permittivity of matter, labeled ε, in the form

.

But the permittivity was measured for static electric fields, and the refractive index was measured for electromagnetic light waves that oscillate rapidly in time. For some materials, this worked pretty well, but for others, it was very inaccurate. Kaufmann mentions water as an example where the relation fails. The static permittivity of water is very high, about 80; its strong electrical response is what allows one to deflect a stream of water with static electricity. The refractive index of water for visible light, however, is 1.33, and clearly the square of this number is not 80!

Furthermore, it was already well-known that the refractive index of matter can depend strongly on the color of light, in a phenomenon called dispersion. The classic example of this is the breaking of white light into a rainbow using a glass prism, as on the cover of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

Now, after a first unsatisfactory attempt by Sellmeier in 1874, H. v. Helmholtz set up a mechanical theory of color dispersion, the basis of which is that the physical molecules have certain natural vibrations.

As early as 1880, i.e. at a time when people in Germany still hardly believed in Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory of light, H. A. Lorentz showed that the fundamentals of an electromagnetic theory of dispersion could be obtained in a manner analogous to the earlier mechanical theory, if one used each molecule as a starting point electrical oscillations of a certain period. It says there: “There may be several material points charged with electricity in every particle of the body, but only one of them with the charge e and the mass m is movable.” With the help of this basic assumption of vibrating charged particles, H.A. Lorentz then derives the dispersion equations.

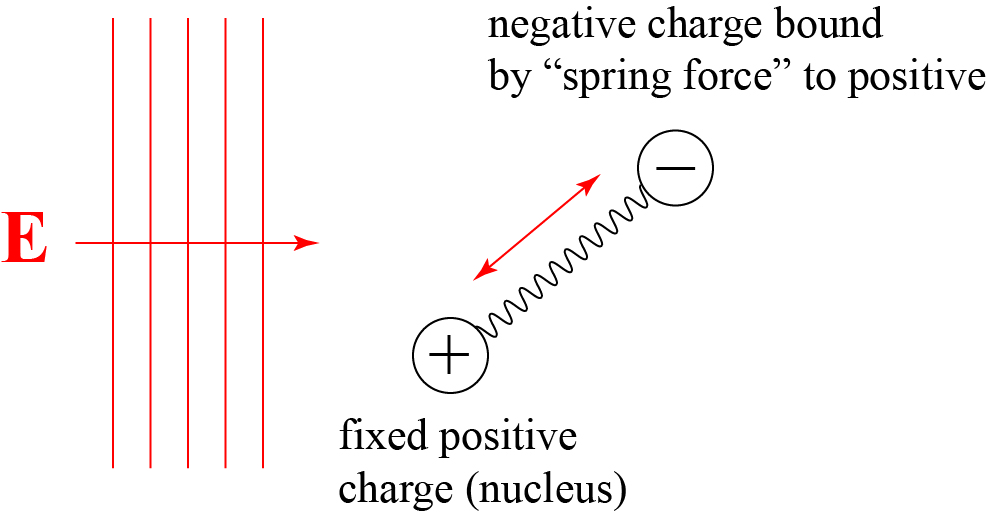

The work of H.A. Lorentz described here is so groundbreaking and fundamental that we still teach it to this day, and it is often referred to as the Lorentz model of the atom. Lorentz made the simple assumption that a molecules consist of positive and negative parts, bound to each other electrostatically with that binding modeled by a simple spring force. He assumed that only one of the molecule’s parts is free to oscillate, and can be set into motion by the electric field of an electromagnetic wave, as roughly illustrated below.

Lorentz’s model is amazing because it long predates any physical model of the atom and knowledge of the existence of electrons and the nucleus. He could not even say for certain which charges, positive or negative, would be set into motion: fortunately for his theory, the results do not depend on this choice.

With this simple model, Lorentz was able to reproduce theoretically the measured dispersion characteristics of many materials, suggesting that he was on the right track. And his model assumes that electric charge is bound in discrete particles, not a continuous fluid, which again hints at the existence of the electron.

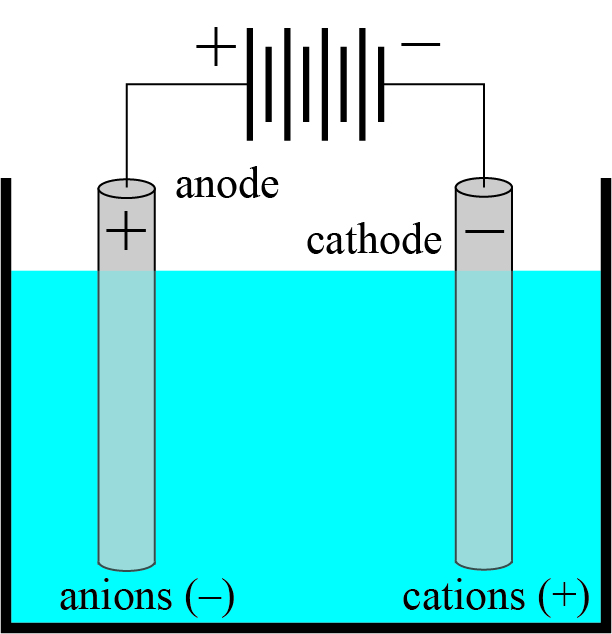

The next question now is: How do we come to assume the existence of electric particles in every transparent body? The answer gives us a field of phenomena that also found it difficult to fit into Maxwell’s theory and was therefore almost always treated according to the old way of looking at things. I mean the processes of electrolysis. According to Faraday’s law, when an electric current flows through an electrolyte, chemically equivalent quantities are excreted at the electrodes for each unit current; the process can thus be viewed as if each chemical valence of each migrating ion in the electrolyte was associated with a definite fixed quantity of electricity, positive or negative.

Electrolysis is the technique by which a direct electric current is used to drive a non-spontaneous chemical reaction. In an electrolyte with free ions, the positive anode and negative cathode draw the anions and cations, respectively, towards them where they undergo reactions to make them neutral.

More from Kaufmann:

In a speech given in memory of M. Faraday in 1881, H.v. Helmholtz points out that from Faraday’s law we must necessarily infer the existence of electric atoms. Since the charged chemical atoms, which Faraday called ions – i.e. the migrating ones – are eliminated as neutral bodies at the electrodes, the charges must be released there or a partial exchange for charges of the opposite sign must take place. During this process, which cannot take place instantaneously, the charges must be able to lead an independent existence, at least for a short time; what could be more obvious than to regard this constant charge unit of a valence as an elementary quantum of electricity, as an electric atom. And if a neutral molecule, say Na Cl (sodium chloride), when dissolved in water, breaks up into + charged Na and – charged Cl, the most probable probability is that the Na and Cl atom each had its charge beforehand, and that these charges remained imperceptible to the outside only because the + and – charges were of the same magnitude. But if you imagine a ray of light passing through a NaCl crystal, then the charges or the atoms connected to them must begin to vibrate and influence the movement of light. It is the electrolytic valence charges that we have to consider as the electric particles oscillating in the transparent bodies, and their attractive forces, as Helmholtz proved, also make up by far the largest part of the chemical related forces.

Long story short: electrolysis indicates that a definite amount of electric charge must be transported per ion in the process, and it is natural to assume that there is an “electric atom” connected with this transport. And if one assumes definite electric atoms exist, then it is natural to assume that those charges are always present in neutral atoms, and that those neutral atoms just have an equal combination of positive and negative electric particles. When researchers looked at the model of the atom introduced by Lorentz and the speculations of Helmholtz, they could see how electrolysis seemed to fit into the picture.

Even if, as mentioned before, the ground plan for the building of the electromagnetic theory of light had already been drawn in 1880 by H.A. Lorentz, and even hinted at much earlier by W. Weber, it still took a full decade before, stimulated by the discoveries made in the meantime by Heinrich Hertz, researchers began to collect and process the building blocks. In the years 1890-1893 a series of works by F. Richarz, H. Ebert and G. Johnston Stoney appeared, which mainly deal with the mechanism of the light emission of luminous vapors and in which, based on the results of the kinetic theory of gases, attempts are made to determine the size of v. Helmholtz’ supposed electrical elementary quantum, for which Stoney suggested the now commonly used name electron.

The result of these calculations is important insofar as it shows us that the figures determined do not contain any contradictions with other experiences.

So e.g. B. H. Ebert, that the oscillation amplitude of an electron in luminous sodium vapor needs to be only a small fraction of the molecular diameter in order to excite a radiation of the absolute intensity experimentally determined by E. Wiedemann.

All the information coming together led researchers closer and closer to the discovery of the electron. G. Johnston Stoney would, in fact, be the person who coined the term “electron.”

The way to calculate the amount of electricity contained in the electron is a very simple one. The quantity of electricity necessary for the electrolytic elimination of 1 cc of any monatomic gas is divided by the Loschmidt number, i.e. the number of gas molecules contained in 1 cc. Given the uncertainty of this latter number, one can only say that an electron contains about 1 in 10 billion electrostatic units. The value of this number would be very problematic if a whole series of other methods, completely different from the one outlined, some of which will be discussed later, had not led to very similar values.

“Electrostatic units” are an early unit of electric charge, still sometimes used in theoretical work but mostly supplanted by Coulombs. An estimate for the charge of the electron using electrolysis led to a value of 1 in 10 billion esu; the modern value is 4.8 in 10 billion esu, so they were remarkably close at the time.

While it was thus shown that the phenomena observed were compatible with the assumption of oscillating ionic charges in terms of magnitude, two papers appeared independently of one another, through which the electromagnetic theory of light became the completed edifice. One of these works, originating from Helmholtz, deals only with the special question of color dispersion in absorbing media; the other, of which H. A. Lorentz is the author, goes much further. Here it is shown how, by assuming oscillating charged particles in the light-permeable bodies, all difficulties that stood in the way of a sufficient explanation of the propagation of light in moving bodies, e.g. the aberration of starlight, are eliminated. Lorentz’s theory leaves Maxwell’s equations for the free ether unchanged. A material body influences the optical as well as the electrical processes only through the mobile charges present in it, while everything remains unchanged in the ether filling the interstices. A “dielectric constant”, as in Maxwell, is no longer a basic concept in Lorentz. Here it becomes a derived concept; and one also sees immediately that it is no longer of any importance for fast oscillations in which the inertia of the oscillating charges comes into consideration. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, to the magnetization constant.

Given the ease with which Lorentz’s theory alone explains the phenomena of dispersion and aberration, direct proof of its correctness would scarcely have been required. Nevertheless, this should not be absent either.

I believe this again is a reference to Lorentz’s model of the atom and the earlier speculations by Helmholtz that lead up to it. One curious thing that is noted here is that “A material body influences the optical as well as the electrical processes only through the mobile charges present in it, while everything remains unchanged in the ether filling the interstices.” Physicists had long believed that light waves oscillated in some sort of material medium that they called an “ether” or “aether.” The discovery that light is an electromagnetic wave needed some sort of way to reconcile light interacting with the aether and with electric charges, and it seems at the time that physicists simply ignored the issue. Eventually, Einstein’s special theory of relativity would make the idea of an aether unnecessary and in fact counter to experimental observation.

In 1896, a student of Lorentz, P. Zeeman, discovered a phenomenon whose existence had already been sought by Faraday (1862) in vain:

If a luminous vapor, say a sodium flame, is placed in a strong magnetic field, the spectral lines of the vapor show peculiar changes, consisting essentially in a doubling or tripling, depending on the direction of vision; Changes that can be fully predicted on the basis of Lorentz’s theory.

Here things get quite interesting! The Zeeman effect, which I will blog about in more detail in a future blog post, is a phenomenon in which spectral emission lines from elements split into two or three lines in the presence of a strong magnetic field. By spectral emission lines, I mean the splitting of the light from an element into its various colors using a prism; the result is a collection of discrete color lines. For hydrogen, the pattern of lines in the visible spectrum looks as follows, via Wikipedia.

In the Zeeman effect, some of these lines will split into three, which implies that some of the atoms are suddenly oscillating at a higher frequency, some at a lower frequency, and some at the original frequency.

Lorentz was able to explain this using his model of the atom. Electrons can vibrate in three directions, corresponding to the three directions of space, and a magnetic field will affect the frequency of vibration in two of the three directions, resulting in the line splitting. This explanation is not quite right, but it gave results close enough to experiment to convince people.

Lorentz’ explanation of the Zeeman effect seemed to provide strong evidence for his model and in turn for “electric atoms.” Furthermore, the explanation allowed the measurement of the mass of the mysterious electric particle:

Zeeman’s phenomenon also made it possible to determine the inertial mass associated with the oscillating charges; and there came a result that is a bit striking: the oscillating electron always ended up negative, while the positive one is fixed; the charge to mass ratio is 17 million emu per gram; Since one gram of hydrogen, i.e. one gram valency, contains only 9650 emu, it follows that the mass associated with the oscillating electron is only about two-thousandth part of a hydrogen atom. The assumption, mostly tacitly introduced at the beginning, that the whole ion, i.e. chemical atom plus valence charge, oscillates, must therefore be dropped; we must assume that the charge in the light-emitting molecule, just as in the electrolytic precipitation at the electrodes of a decomposition cell, has an independent mobility, and that the mass involved in the Zeeman phenomenon is precisely that of the electron itself.

This was the first indication that the mobile charge in the atom was much less massive than the other parts of the atom itself. Today measurements have the electron at 1/1837 of the mass of the proton.

With that we would have arrived at a view that almost coincides with the old Weberian assumption, with the important difference, however, that the mediated effect, propagated through the ether, has replaced the direct long-distance effect and that we now have a very specific numerical idea of the size of electric atoms. And one more difference from Weber must be emphasized here. On a whim, Weber always assumed the positive particles to be the freely moving ones in his theoretical considerations. Due to the Zeeman effect, we now always have to grant this position to the negative ones. It turned out that in all other phenomena in which the electrons come into consideration, and of which we will get to know some later, the negative electron always appears as freely mobile. Where does this remarkable one-sidedness come from, whether it will be possible to prove the free positive electron one day, or whether we might have to let a unitary conception of electricity take the place of the dualistic one? We must leave that to the future to decide.

This work also demonstrated that the negative charges are the mobile ones, as we now know to be true. Electrons move freely, while protons are bound in a much heavier nucleus. Kaufmann notes that Weber’s original guesses were largely correct, except that Maxwell had shown that electric and magnetic disturbances propagate as a wave, not instantaneously.

The development of the concept of electrons just outlined in the field of light theory was very soon followed by a very corresponding one in a purely electrical field:

The electrical discharges in gases had long been tried to be regarded as a process related to electrolysis. It is W. Giese who first gave important support to this hypothesis by investigating conduction in flame gases and also attempted to explain conduction in metals by migration of ions.

Here, we find that electron theory started to be useful to explain all sorts of processes, such as electrical discharges in gases.

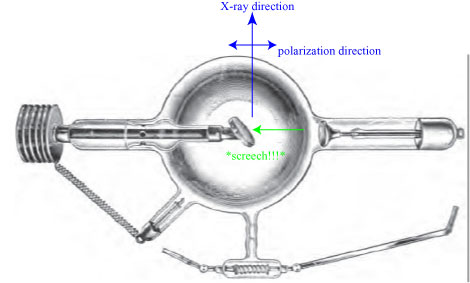

Above all, however, it was the so-called Cathode rays, now again receiving the greatest attention, partly as a result of the discovery of X-rays at the end of 1895 — Plücker and Hittorf were the first to study more closely the peculiar green fluorescence of the glass walls in very heavily evacuated discharge tubes. In the course of further investigations, in which E. Goldstein made a name for himself, it became apparent that this must be a peculiar type of radiation, which emanates from the negative electrode, the cathode of the tube, and which is why Goldstein got its name “cathode rays” suggested. Crookes tried to explain the behavior of these rays in the magnetic field, their thermal effects, their supposed mechanical effects by assuming that these rays consisted of gas molecules that were negatively charged at the cathode, repelled by it as in the electric ball dance and thrown into the tube space. In fact, most of the phenomena observed could be reasonably explained by this hypothesis.

Cathode rays are are invisible rays that emanate from the cathode in an electrical cathode ray tube; an illustration of such a tube is shown below.

Cathode rays produce a green fluorescence when they hit the opposite wall of the tube, which is how they were first discovered. Experiments with magnets showed that they were negatively charged with electricity, and Crookes assumed that lingering gas molecules in the tube somehow picked up a negative charge at the negative cathode and were thus repelled away from it. This explanation was, of course, incorrect; the cathode directly emits electrons that are drawn towards the anode or anticathode.

However, more precise investigations, especially numerical tests, very soon proved the untenability of Crookes’ hypothesis, at least in its original form. Unfortunately, especially in Germany, the baby was thrown out with the bathwater; the whole hypothesis was rejected because the very specific notion that they were contact-charged molecules turned out to be wrong. But one could not put anything better in its place; the more facts were accumulated, the more mysterious became the cathode rays, and finally it came to the point that it was almost unworthy of a decent physicist to concern himself with these phenomena, so inaccessible to quantitative and theoretical treatment. Suddenly there came the most enigmatic of all the enigmatic: the discovery of X-rays through Röntgen and with it a new spur to tackle the solution of the many questions. The effort put in should soon be crowned with success.

I found this paragraph interesting, because of the use of the “baby thrown out with the bathwater” saying, which I had never seen in a scientific paper before! In short, Kaufmann is saying that because Crookes’ hypothesis of charged molecules didn’t seem to work, researchers turned away from the entire idea that cathode rays are charged particles. But the discovery in 1895 of X-rays being emitted from cathode ray tubes turned researchers back to investigate them again, and at last almost all questions would be answered.

The investigations of E. Wiecherts, W. Kaufmann and E. Aschkinass, W. Kaufmann, J. J. Thomson, W. Wien, Ph. Lenard, T. Des Coudres showed unanimously that it only required a modification of Crookes’ hypothesis in order to arrive at a to arrive at a consistent explanation of almost all phenomena: One only needs to regard the cathode rays as charged mass particles, which are much smaller than ordinary atoms. A whole series of measurable properties of the cathode rays makes it possible to determine how large the charge per gram mass is for these particles. The result was somewhat different for different observers, it fluctuated between 7 and 19 million emus per gram; In any case, however, these numbers are so close to those found for the Zeeman effect that one can absolutely agree with the hypothesis first expressed by E. Wiechert that we are dealing with the same particles in both cases, namely the electrons: In the cathode rays, therefore, we have the electrons, which lead a fairly hidden existence in optical phenomena, physically before us, so to speak.

Finally, researchers came to an agreement that all of the phenomena observed could be explained by the existence of a single mobile negative charge carrier — the electron! Though estimates for the mass of this particle varied, the numbers were close enough in these early experiments to convince everyone of the hypothesis.

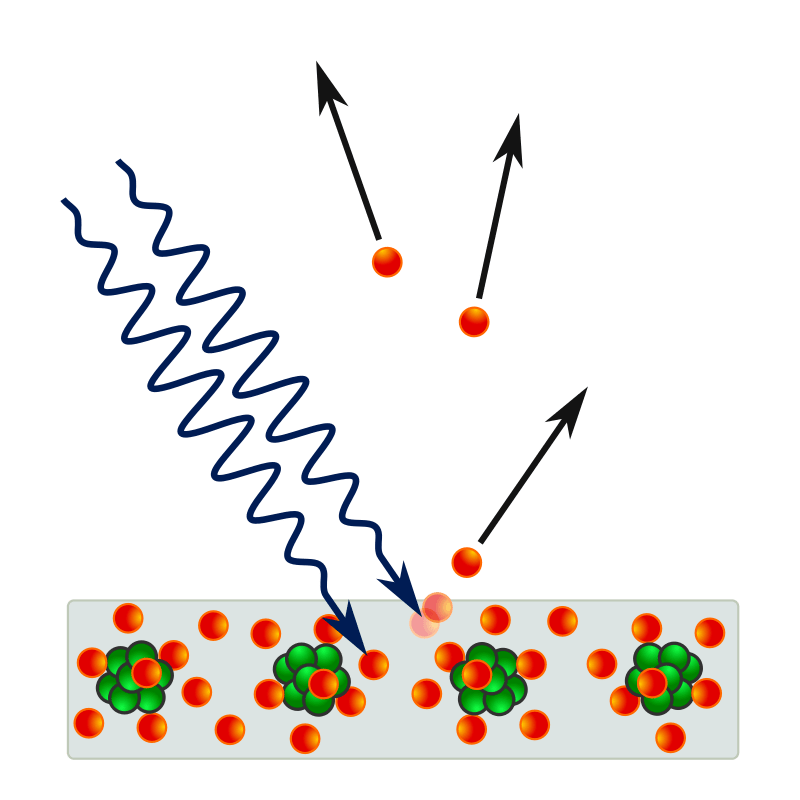

A number of consequences can now be explained in a simple manner. Such an electron flying with enormous speed, according to direct measurements by Wiechert, depending on the applied force with 1/5 to 1/3 of the speed of light, must, if it hits a solid body, necessarily send an explosive electric wave out into space, just like a hitting projectile, a sound wave; we have good reason to believe that the X-rays are such waves. Furthermore, when the electrons fly out of the surface of the cathode, they must have already moved towards the surface in its interior; i.e. the electrical conduction in the metal also consists of a migration of electrons. So while in the liquid electrolyte the electron always appears bound to a material atom as an “ion”, in the metal we are dealing with freely roaming electrons. This electron theory of metals, of which we must also regard W. Weber as the first author, has recently been worked through mathematically by E. Riecke and P. Drude to such an extent that it permits a test based on experience; a figure was found for the relation between electric and heat conduction of the metals, which agrees with the observations to within a few percent; the optical behavior of the metals also seems, as far as observations go, to be in good agreement with this theory; and by P. Lenard it has been shown that by irradiating a metal surface with ultraviolet light, the electrons of the metal can be made to resonate so strongly that they fly away from the surface with great speed and then show a behavior very similar to that of the ordinary ones, cathode rays generated by discharges.

With electrons as fast-moving particles, the appearance of X-rays could be readily explained. Maxwell’s theory indicated that accelerating charged particles produce electromagnetic waves; when electrons crash into an anode, then, the X-rays they produce are clearly the predicted electromagnetic waves. It took a few more years for this to be conclusively proven, but everything started to make sense.

Others started to use the electron theory to explain properties of matter. Drude created a model for electrical conductivity based on atoms, and the photoelectric effect discovered by Lenard could be explained as electrons being liberated from a metal surface by light waves.

Finally, if we consider the conduction in any gas, which we have made conductive by irradiation with X-rays or ultraviolet light, or by strong heating, we see here too that a correct explanation of the numerical results, as given by J. J. Thomson and obtained from his students is only possible under the assumption of moving particles in the gas; from certain differences in the behavior of the positive and negative particles in these processes it seems to appear that the negative particles are chiefly free electrons, most of which, however, are caught by gas molecules after a short migration, and, burdened by them, lose a large part of their original mobility. The positive particles then consist of the residue remaining after a negative electron has been split off from the molecule. The way of looking at things just outlined completely eliminates an objection which was sometimes used to refute the ion theory of conducting gases. How, it has been said, can a monatomic gas, such as mercury vapor, dissociate into ions? Not into electrolytic ions, but into a positively charged atom and a negative electron. Both together only form the neutral monatomic molecule. By observing conducting gases, even J. J. Thomson has succeeded in directly measuring the absolute magnitude of the charge of a single ion, which agrees quite well with the values of the elementary quantum discussed earlier. Let us add that recently, in a third, completely independent way, from the radiation laws of the so-called “black body” by M. Planck an almost equal value of the electron was found.

Electrical conduction in a gas is another question that was answered by the presence of electrons. When illuminated by X-rays or ultraviolet light, a gas becomes more conductive. This conductivity was attributed to the creation of charged ions that could then carry their charge between electrical leads. For molecules like CO2, it was reasonable to assume that the component atoms were separated and carried individual charges, but such an explanation did not work for gases like mercury, which consist of single neutral atoms but still become conductive. Now it became clear that electrons were part of every atom, and could be split away from individual atoms, leaving positive ions and mobile electrons.

Thomson managed to measure the charge of the electron, and found good agreement with the electrolysis value found previously. Furthermore — and this is something that I need to investigate — apparently Max Planck came up with a third consistent estimate of electric charge in his studies of blackbody radiation.

Everywhere, therefore, in all aggregate states, the electrons play their important role in electrical and optical processes; they are the smallest known components of our visible world; Their occurrence even in the absence of external electrical or optical influences, i.e. the direct proof of their constant existence, would form the keystone, so to speak, in the logical edifice whose origin I have attempted to enact for you; we don’t have to look far for this keystone either.

This paragraph highlights what a big deal the discovery of the electron was. Here, for the first time, physicists had a truly fundamental building blog of nature within their grasp.

Shortly after the discovery of X-rays, Becquerel found that uranium compounds emit a type of radiation that is very similar to X-rays, and G. C. Schmidt later showed that thorium compounds also emit similar rays. Further investigations, in particular by the physicist couple Curie, showed that these rays did not emanate from the uranium itself, but from certain admixtures, which can be separated from the uranium by an extremely laborious fractionation process and finally concentrated so that they radiate about 50,000 times more strongly than that Uranium. It seems that the end product, which essentially consists of a barium salt, contains a new element, which has been given the name radium – the radiant – which, of course, by no means proves that precisely this new element is the starting point of the radiation. Now, these Becquerel rays, which at first were thought to be closely related to the X-rays, were found by Giesel and soon afterwards by Becquerel to be magnetically deflectable and thus much more likely to be placed in parallel with the cathode rays. After Dorn and Becquerel had also established and, if only roughly, measured the electrical deflectability, the velocity and charge per unit mass of these rays could also be calculated, the order of magnitude agreeing with the figures obtained for cathode rays. From the speaker’s latest, more precise experiments, there even seems to be complete agreement.

It is somewhat comical how physicists suddenly started to find electrons everywhere once they made the official discovery. Becquerel’s discovery was in 1896, just before the discovery of the electron. Soon, three types of radiation were discovered, alpha rays (helium nucleus), gamma rays (high energy photons), and beta rays (electrons). Thus the electron found itself at the center of another new, mysterious phenomenon.

Thus in the radium salts we have a class of bodies capable of ejecting electrons of their own accord, without any external influence. We are still completely puzzled as to the source of energy and the whole mechanism of this phenomenon, especially since we are dealing here with velocities that are almost equal to the speed of light, velocities that we can only achieve through electrical forces, i.e. in the case of real cathode rays, certainly only after overcoming them of the greatest difficulties can reach. However, the behavior of the electrons at such enormous velocities seems suitable for providing information about the deepest questions about the constitution of the electrons. Above all, direct measurement can be used to decide whether the mass of the electrons is perhaps only “apparent”, simulated by electrodynamic effects. The experiments so far actually speak for the assumption of an “apparent” mass.

The high speeds of beta radiation suggested more new physics, which would eventually be tied to the forces within the nucleus itself. But the nucleus was almost a decade away from discovery at this point.

Kaufmann seems to be referring to his own work here in his discussion of “apparent” mass, since in that same year he showed that electron mass seemed to increase as the electron speed approached the speed of light. This apparent mass change would eventually be found to be a relativistic effect.

And this brings us to a question that goes deep into the structure of matter in general:

If an electric atom behaves exactly like an inert mass particle simply by virtue of its electrodynamic properties, is it not then possible to regard all masses as merely apparent? Instead of all the fruitless attempts to explain electrical phenomena mechanically, shouldn’t we try, conversely, to trace mechanics back to electrical processes? Here we come back to views cultivated by Zöllner 30 years ago and recently taken up and improved again by H. A. Lorentz, J. J. Thomson and W. Wien: If all material atoms consist of a conglomerate of electrons, then their inertia comes naturally.

Before relativity, however, researchers were led down a fascinating false path: looking for electromagnetic origins for mass itself. If an electron carries with it electric and magnetic fields, and those fields carry energy, then the fields themselves would provide some inertia to the particle that would appear to be mass. It was wondered if the electron had any real mass of its own, or if it all came from electrical effects. Again, relativity would largely negate these speculations.

To explain gravitation, it must also be assumed that the attraction between unlike charges is somewhat greater than the repulsion between like ones. An experimentum crucis for this view would be the proof of a temporal propagation of gravitation respecting its dependence not only on the position but also on the speed of the gravitating body.

If mass is just an electrical effect, it stood to reason that gravity must also be some sort of electrical effect. This, again, has been largely debunked, but it is worth noting that there might be some truth in it if we ever find a unified theory of nature that links all fundamental forces together.

The electrons would then be the “primeval atoms” sought by many, whose various groupings form the chemical elements; the old alchemist’s dream of the transformation of the elements would then have come much closer to reality. One might assume, for example, that among the innumerable possible groupings of electrons only a relatively limited number are stable enough to occur in large quantities; these stable groupings would then be the chemical elements we are familiar with. By treating these questions mathematically, one day it may be possible to show the relative abundance of the elements as a function of their atomic weight and perhaps also to solve many other mysteries of the periodic table of the elements.

Here Kaufmann seems to be talking about a hypthetical positive electron that could form the elements; this is not far removed from our modern understanding of a nucleus filled with positive protons and neutral neutrons.

If we cast a look away from the earth into space, we see many a phenomenon there too, to which attempts have been made to apply the electron theory, not without prospects of success; the solar corona, the comet tails and the northern lights belong here.

At least, we return to an oblique reference to Zöllner, who attempted to explain comet tails with early conceptions of the electron.

Even if some of this seems a bit too hypothetical, it should be clear from what has been said that the electrons, these tiny particles, whose size is related to that of a bacillus as that of a bacillus is to that of the entire globe, and their properties we but able to measure with the greatest precision that these electrons form one of the most important foundations of our entire world structure.

We conclude, and Kaufmann concludes, by again stressing what a big deal the discovery of the electron was. For the first time, though not the last, physics had in its hands (laboratories) a fundamental building block of nature. We have seen that the discovery of the electron was not accidental, but the natural culmination of decades of experiments and speculation. It is a fascinating and rich piece of history.

(Whew okay I’m done!)