Every once in a while I come across an off-hand comment that immediately makes me need to know more. Recently, I’ve been researching the history of light polarizers, and turned to a paper1 by Edwin Land, the scientist who developed the first commercial sheet polarizers in the 1920s. His historical retrospective contains the quite attention-getting sentence,

In the literature there are a few pertinent high spots in the development of polarizers, particularly the work of William Bird Herapath, a physician in Bristol, England, whose pupil, a Mr. Phelps, had found that when he dropped iodine into the urine of a dog that had been fed quinine, little scintillating green crystals formed in the reaction liquid.

Soooo much to unpack here. Why was a dog being fed quinine? Why were the collecting the urine of the dog, and how did they accidentally drop iodine into it? Is there any truth to this story at all, for that matter?

Let’s take a look at this story and how it would eventually revolutionize optics, starting with a brief discussion of the polarization of light…

The recognition that light is a wave can be traced back to Thomas Young and his double slit experiment that was done in the first decade of the 1800s, stretched over several years and iterations. The wave nature of light wouldn’t be fully appreciated for at least another decade, however, until additional experiments confirmed its reality.

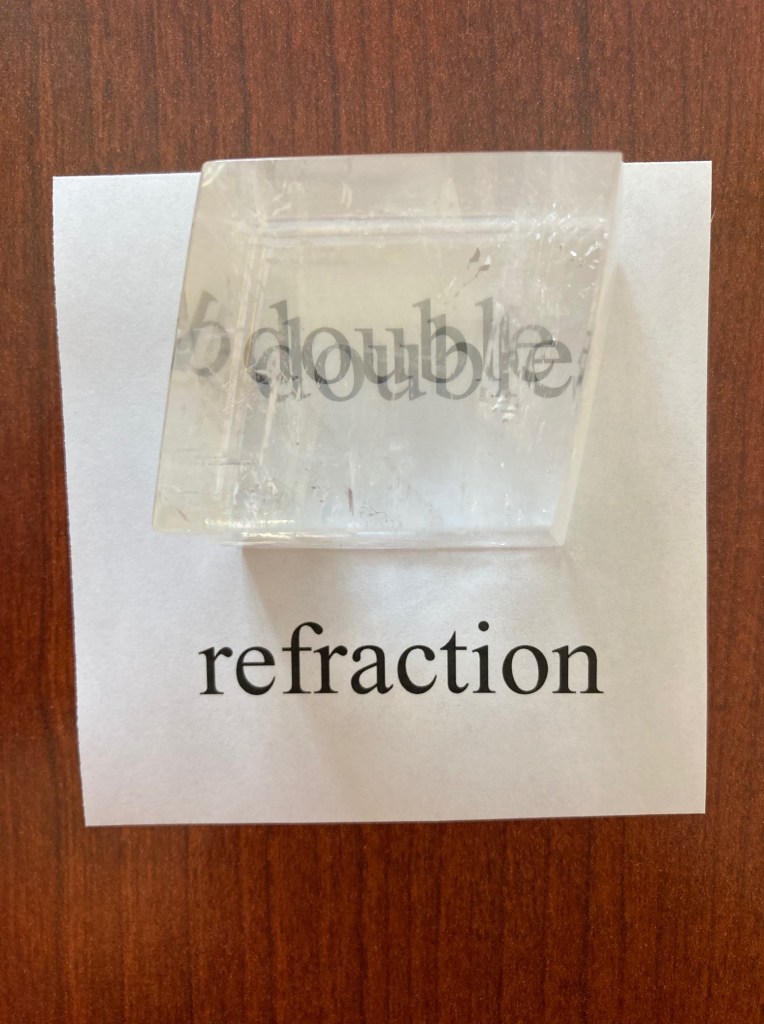

This wave nature answered many previously unexplained questions about optics. One of the most puzzling phenomena was double refraction, in which one sees two images when looking through a piece of optical calcite, as shown below with my own piece.

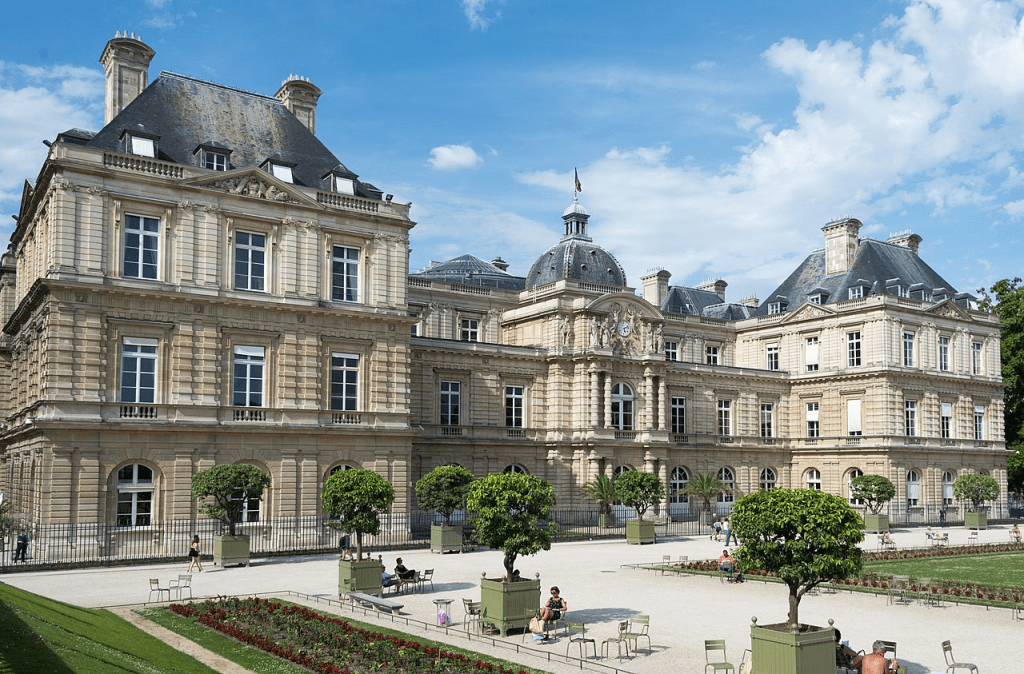

Why do two images appear through calcite, and some other crystalline materials? A piece of the puzzle fell into place in 1808, when French physicist Étienne-Louis Malus was study double refraction and happened to look through a sample of calcite at sunlight reflecting off of the windows of the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. He saw to his amazement that one of the images of reflected sunlight appeared brighter than the other — and by rotating the crystal, he could change which image was brighter.

With some orientations of the crystal, one of the images would vanish entirely, and Malus referred to the light in this state as “polarized,” and the terminology has stuck.

The preliminary explanation of this phenomenon came from none other than Thomas Young, who in 1817 penned a letter to Francois Arago speculating that light is a transverse wave. In other words, whatever is “waving” in light is waving perpendicular to the direction that the light is traveling. We can always choose two distinct directions perpendicular to a wave direction — for example, if we label perpendicular coordinate axes in three-dimensional space as x, y, z, and we take the wave traveling in the z-direction, we can have distinct transverse wave oscillations along x and y. Natural light, from the sun or candles or light bulbs, is “unpolarized,” meaning that it tends to be a random, rapidly-changing combination of x- and y- oscillations. Each of these “polarizations” of light is refracted differently when passing through the crystal, in a phenomenon known as “anisotropy,” and this results most of the time in two images whenever one looks through the crystal. Why did Malus only see one in reflection? We’ll come back to that in a minute…

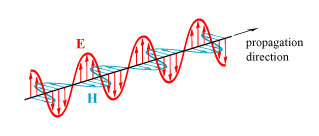

One of the big questions that arose in realizing that light is a transverse wave is: what is waving? The answer was provided by James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s, when he made a convincing argument that light is a transverse electromagnetic wave: the electric and magnetic fields associated with a light wave are oscillating perpendicular to the wave direction. A standard illustration of this is shown below.

This is a diagram showing what the fields would look like at one moment of time along a line following the propagation direction. If we imagine that the propagation direction is into the page, then the electric field E in this illustration is waving up-and-down and the magnetic field H is waving left-and-right. This is the picture that we will keep in mind going forward.

Once the polarization of light was discovered, researchers were of course interested in working with polarized light. The problem, as we mentioned, is that traditional natural light sources produce unpolarized light! Techniques were needed to polarize a light wave, and several would be developed over the next fifty years. The simplest of these is to reflect a light wave off of a transparent surface like glass at an angle called the Brewster angle. At this certain special angle, all of the vertically polarized light is transmitted into the glass, while part of the horizontally polarized light is reflected. The result is a horizontally polarized beam of light, as illustrated below.

This technique is essentially what Malus discovered when he looked at the windows of the Luxembourg Palace through optical calcite: the reflected light was polarized.

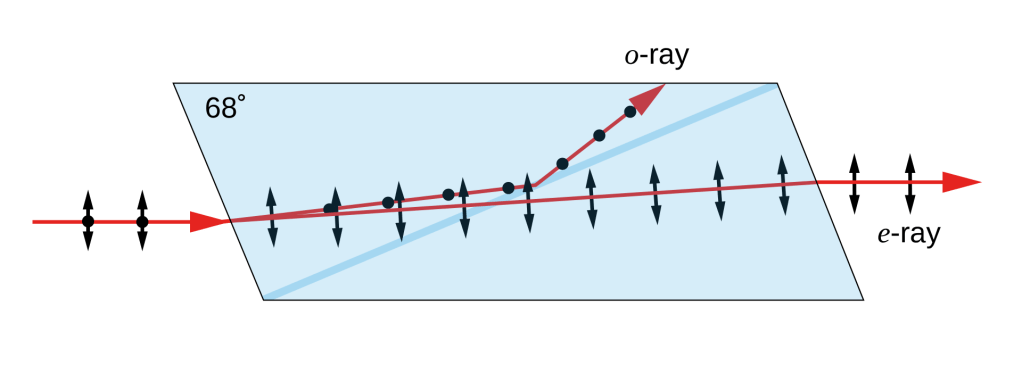

Another option is known as a Nicol prism, invented by William Nicol in 1828. An illustration of light passing through such a prism, via Wikipedia, is shown below.

Here the action of the prism is based on the principle of total internal reflection, in which light going from a denser (higher refractive index) medium to a rarer (lower refractive index) medium will be completely reflected if incident beyond a certain critical angle. Remember that I said that the effective refractive index of a medium depends on polarization in a crystal? In a Nicol prism, the “ordinary” ray gets refracted at the entrance surface beyond the angle of total internal reflection, causing it to get completely reflected out of the path of light, leaving only the polarized “extraordinary” ray to be transmitted.

Both of these polarization techniques are less than ideal. In most optical systems, it is desirable to have all the elements aligned along a straight path, or with very simple angular deviations via mirrors. In both the Brewster method and the Nicol method, the desired light beam is deviated from its original path, making optical alignment more difficult.

A third method, which seems to have been discovered not long after Malus discovered polarization, is the use of the crystal tourmaline as a polarizer. Tourmaline, like optical calcite, is an optically anisotropic material. The difference is that tourmaline absorbs light of one polarization quite strongly and the other polarization quite weakly. Passing light through a thin sheet of tourmaline therefore results in a polarized beam of light. There were two downsides in using tourmaline as a polarizer back in the day. First, the varieties of tourmaline useful for polarizers tended to have a greenish color, a not ideal situation if one wishes to study polarization of light of colors other than green. Second, tourmaline was relatively expensive, limiting how much any researcher could afford for their work. (This was also a problem for Nicol prisms, which were relatively expensive to make.)

So by the mid-1800s there were several different types of polarizers available, but none that really simultaneously matched the two desirable properties “inexpensive” and “thin and flat.” This would set the stage for William Bird Herapath’s transformative discovery, though it would take many years before it would reach its full potential.

William Bird Herapath (1820-1868) was an English surgeon and chemist. He was awarded his M.D. in 1851 and by 1852 he was already working as a surgeon at several institutions in Bristol. He also did much work in chemistry, and was the son of a prominent Professor of Chemistry at Bristol Medical School, William Herapath. It doesn’t necessarily add anything to this tale, but I must share this anecdote2 about William Herapath Sr. that I came across:

Besides being a distinguished chemist , Mr. Herapath was a town counciller and a magistrate of some repute. He had a rather quick temper. One snowy morning in winter he had just retired after his chemical lecture, and was walking down the Medical School yard , when some parting shots in the shape of snowballs were fired at him from one of the Medical School windows in the rear . One of these knocked off his hat and quite upset his equanimity. He at once faced round and said: ” If I knew who threw that snowball, I’d sink the magistrate, I’d sink the lecturer , and give him as good a thrashing as ever he had in his life ! ” This little episode rather increased the medical students’ respect for him; for they regarded him as a man who was ready to fight if necessary.

I have found no description of William Bird Herapath’s temper, it is evident that he carried on his father’s interest in chemistry, in particular in medicine. I have not found any early publications on his work, but it is clear from what follows that he was studying the effects of quinine, the first antimalarial drug, on the human body. The bark of the cinchona tree had been recognized as an effective treatment for malaria in the early 1600s, but the active chemical quinine was only extracted from the bark in the 1820s and the widespread use of the drug began in the 1850s, making it a ripe subject for clinical analysis.

It is not exactly clear what research Herapath was doing at this point, but we know the details of the happy accident that followed, as he reported in his first publication3 on the subject:

Some short time since my pupil called my attention to some peculiarly brilliant emerald-green crystals, which had formed by accident in a solution of the disulphate of quinine. He could give me no account of their formation. Some experiments made upon them convinced me of their importance, both chemically and optically, and led me to suspect that iodine was in some way necessary to their composition.

Upon dropping tincture of iodine into the solution of disulphate of quinine in diluted sulphuric acid, an abundant deposition of similar crystals immediately occurred.

Here we have the immediate description of the serendipitous discovery, similar to what Land had suggested but with some key differences. There is no mention of urine in the discovery, nor of a dog. The “disulphate” pretty much rules out urine in the first place, as it is the salt of disulfuric acid, which in my limited chemical experience seems like something that would be extremely bad to be inside of a living creature. Let us table the question of Land’s story and learn more about what Herapath did next:

Upon dropping tincture of iodine into the solution of disulphate of quinine in diluted sulphuric acid, an abundant deposition of similar crystals immediately occurred. However, it was found exceedingly difficult to experiment in a satisfactory manner

upon the crystals thus formed, as it was almost impossible to isolate them from their mother-liquid. It was subsequently found, that by dissolving the disulphates of quinine and cinchonine of commerce in concentrated acetic acid, upon warming the solution, and dropping into it a spirituous solution of iodine carefully by small quantities at a time, and placing the mixture aside for some hours, large brilliant plates of this substance were

produced. These could be readily separated from their mother-liquid, and by frequent recrystallization, purified.

The development of crystals was interesting enough, but what was more interesting was the optical properties of the grown crystals:

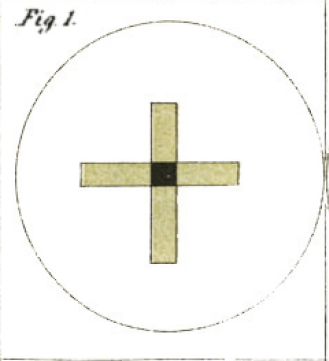

The crystals of this salt, when examined by reflected light, have a brilliant emerald-green colour, with almost a metallic lustre ; they appear like portions of the elytra of cantharides, and are also very similar to murexide in appearance. When examined by transmitted light, they scarcely possess any eolour, there is only a slightly olive-green tinge; but if two crystals crossing at right angles be examined, the spot where they intersect appears as black as midnight, even if the crystals are not 1/500dth of an inch in thickness. (See Plate IV. fig. 1.) If the light used in this experiment be in the slightest degree polarized, as by reflexion from a cloud, or by the blue sky, or from the glass surface of the mirror of the microscope placed at the polarizing angle, 56 ° 45 r, these little prisms immediately assume complementary colours. One appears green and the other pink ; and the part at which they cross is a chocolate or deep chestnut-brown

instead of black.

Herapath recognized that the crystals he had grown were natural polarizers like tourmaline! The “Plate IV, fig. 1” he references is shown below.

This is an illustration of the view of two crossed crystals, presumably through a microscope. Where the crystals intersect, no light passes through at all. One crystal is blocking horizontal light, the other vertical: together, they allow no light to pass through at all.

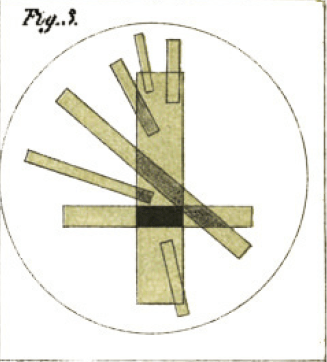

Herapath tested out the polarizing properties of his crystals in detail, looking at how crystals overlapped at different angles will block light, as illustrated by his figure below.

As one would expect, a second crystal placed nearly parallel over the first will not appreciably block more light, but as the two crystals become perpendicular, the light obstruction becomes complete.

Herapath also recreated a classic polarizer experiment; his description is below.

When three crystals are examined in a superimposed condition, two being crossed at right angles, and therefore dark, and a third introduced between them, the phenomena of depolarization are produced: the interposed crystal permits the light to pass through, and at the same time communicates to it the order of colour, equivalent to its thickness, in the same manner as a plate of selenite would do if interposed between two tourmalines

at right angles to each other.

This is the classic “three polarizer” experiment of optics, in which a third polarizer placed at 45 degrees to two crossed polarizers will allow some light through. The video below is my recreation of it from some years ago.

Herapath also illustrates this phenomenon in his paper:

To explain this, let’s refer to the three crystals as “left,” “right,” and “top.” Where the left and right crystals overlap, there is no light passing through — these are the two crossed polarizers. The top crystal, interposed between the other two, allows a significant amount of light to pass through, shown as the pink section of the slide.

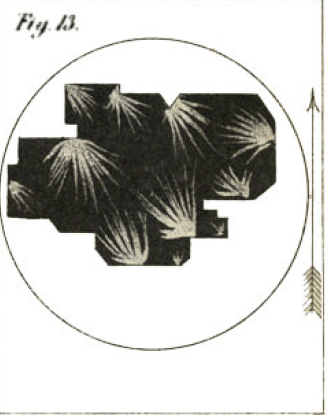

One more figure is worth sharing here, just for its beauty: Herapath had difficulty trying to get one single sheet of his new material to act as a large polarizer; however, he was able to clump together multiples on a microscope stage on top of a slab of tourmaline, acting as a polarizer itself, and see lovely patterns due to the various orientations of the crystals:

The arrow in the figure indicates the angle of polarization that the tourmaline induces on the light passing through it. Herapath found that his crystals were also much better at polarizing light than tourmaline — roughly speaking, a sample of his crystals could provide the same polarizing power that would be provided by a sample of tourmaline five times thicker.

The rest of Herapath’s paper focuses on the chemistry of the crystals, and how to grow them. Herapath recognized that he had made an important discovery here, and was hoping to perfect the process to grow crystals large enough to cover the field of view of a microscope. He provided improved techniques in a paper4 published the next year, “On the Manufacture of large available Crystals of Sulphate of Iodo-quinine (Herapathite) for Optical Purposes as Artificial Tourmalines.” One should note the use of the name “Herapathite” for the new crystalline substance; this was introduced by the Austrian minerologist Wilhelm Haidinger in a paper published5 the same year as Herapath’s. Herapath himself noted this new designation at the end of his own publication, showing a bit of discomfort and amusement in it:

I have invariably used in this description the original terms employed by me, namely, “artificial tourmalines” and “crystals of sulphate of iodo-quinine.” Professor Haidinger’s term of “Herapathite ” is certainly a highly complimentary one to myself; hut as it does not give either an idea as to the optical properties or chemical characters of the substance in question, it does not appear to me so suitable as those I originally attached to them.

Sadly, in none of the papers mentioned so far have we found mention that the discovery came from actual quinine-saturated dog urine. I have found several other papers by Herapath on his crystals, and the story is always the same, involving a solution of disulphate of quinine. This raises the obvious question: where, exactly, did Edwin Land get his anecdote about the discovery involving dog urine?

A hint of the answer can be found in Herapath’s original paper on Herapathite, in which he notes:

It now became an interesting question to decide whether any other of the vegetable alkaloids would act in a similar manner with iodine. The same experiments were tried with the salts of morphine, brucine, strychnine, salicine and cinchonine, but without

success ; we may therefore almost confidently depend on the production of these crystals being indicative of the presence of quinine in a given solution.

In other words: quinine is apparently essential to the formation of crystals and thus, going a step further, the formation of the crystals can be used as a reliable detector of quinine in a solution. This was the argument made by Herapath in another 1853 paper6, “On the discovery of quinine and quinidine in the urine of patients under medical treatment with the salts of these mixed alkaloids.” Herapath proposes using the formation of Herapathite to study how much quinine lingers in the body after being ingested, and whether it passes fully through the body and out through the urine or is taken up long-term by human tissue. In his own words,

It has long been a favourite subject of inquiry with the professional man to trace the course of remedies in the system of the patient under his care, and to know what has become of the various substances which he might have administered during the treatment of the disease. Whilst some of these remedies have been proved to exert a chemical change upon the circulating medium, and to add some of their elements to the blood for the permanent benefit of the individual, others, on the contrary, make but a temporary sojourn in the vessels of the body, circulating with the blood for a longer or shorter period, but are eventually expelled and eliminated from it at different outlets and by various glandular apparatus; some of these substances are found to be more or less altered in chemical composition in consequence of having been subjected to the manifold processes of vital chemistry during their transit through the system, whilst others have experienced no alteration in their constitution, but have resisted all the destructive and converting powers of the animal laboratory, and by appropriate means have been again separated from the various excretions by the physiological and pathological Chemist in their pristine state of purity.

Here we may have the genesis of the dog urine story, passed down and misremembered by scientists over the years. The fact that Herapath used herapathite as a test for quinine in human urine evolved grapevine-style into a story that it was in fact discovered in urine. Not sure how the dog fits into this, though!

Hopefully Herapath got some use out of herapathite for diagnostic purposes, because it would not be used effectively in optics during his lifetime. The crystals remained quite difficult to grow in large sizes, and this process would only be done successfully and reliably in the 1930s7 by Ferdinand Bernauer. Just before that, however, in 1929, Edwin Land had found an easier way to make Herapathite into reliable polarizers: by using the smallest herapathite crystals possible. Here we can quote from Land’s 1951 retrospective:

Then came the most exciting single event in my life. The suspension of herapathite crystals was placed in a small cell-a cylinder of glass about a half-inch in

diameter and a quarter-inch in length. The cell was placed in the gap of a magnet which could produce about 10,000 gauss. Before the magnet was turned on, the Brownian motion caused the particles to be oriented randomly so that the liquid was opaque and reddish black in color. When the field was turned on-and this was the big moment-slowly and somewhat sluggishly the cell became lighter and quite transparent; when we

examined the transmitted light with a Nicol prism, it went from white to black as the prism was turned. This first polarizer experiment was a success, but in the twenty-five years between then and now, there have been many technical details which required solution.In making a solid polarizer from a liquid polarizer, the following steps were taken: The same suspension was placed in a test tube and a plastic sheet was dipped into it; the test tube as a whole was placed in the magnetic field and then the tube was withdrawn so as to leave a coating of the dispersion of polarizing crystals on the sheet; the sheet was then allowed to dry in the magnetic field, and a few moments later we had a polarizer.

Let’s try to explain this in less technical detail. Instead of trying to grow a single large herapathite crystal, Land created a microscopic solution of these crystals. In solution under ordinary circumstances, these crystals were all randomly oriented and the solution appeared black. But the crystals are magnetic, and would align to a magnetic field: by placing the solution in a magnet, he found that the herapathite solution as a whole became one large polarizer! Then a plastic sheet was dipped into the solution, getting oriented crystals stuck to it. When the solution was removed and the plastic sheet was allowed to dry, the result was a sheet polarizer: the first Polaroid polarizing film. This led to Land forming the Polaroid Corporation, which later became known more for its instant film cameras.

The creation of Polaroid polarizing film was a game-changer for optics, allowing polarized light to be used much more easily for many applications — I will have another blog post about this in the near future! But this would not have been possible at all if William Bird Herapath’s assistant hadn’t accidentally dropped some iodine in the disulphate of quinine. I’m a bit disappointed that the discovery evidently didn’t involve dog pee, but the discovery of herapathite is still a remarkable and fascinating tale of serendipity.

**********************************************************

- E. Land, “Some Aspects of the Development of Sheet Polarizers,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. 41 (1951), 957-963.

- A. Pritchard, “The Early History of the Bristol Medical School,” The Bristol Medico-Chirurgical Journal 10 (1892), 264-291.

- W.B. Herapath, “On the optical properties of a newly-discovered salt of quinine, which crystalline substance possesses the power of polarizing a ray of light, like tourmaline, and at certain angles of rotation of depolarizing it, like selenite,” Phil. Mag. 3(17) (1852), 161-173.

- W.B. Herapath, “On the Manufacture of large available Crystals of Sulphate of Iodo-quinine (Herapathite) for Optical Purposes as Artificial Tourmalines,” Phil. Mag. 6(40) (1853), 346-351.

- W. Haidinger, “Über die von Herrn Dr. Herapath und Herrn Prof. Stokes in optischer Beziehimg untersuchte Jod-Chinin-Verbindung.” Ann. Physik 89 (1853), 250.

- W.B. Herapath, “On the discovery of quinine and quinidine in the urine of patients under medical treatment with the salts of these mixed alkaloids,” Phil. Mag. 6(38) (1853), 171–175.

- F. Bernauer, “Neue Wege zur Herstellung von Polarisatoren.” Fortschr Miner 19 (1935), 22.

The story of dog urine and Herapath is widely reported, thanks to Land’s colorful story. You prompted me to dig into it a bit more. In addition to reading Land’s talk/paper, and Herapath’s original publication (in which there is no mention of urine of any sort), I noticed that Land says he became aware of Herapathite after reading David Brewster’s book The Kaleidoscope, Its History, Theory, and Construction. Land cites the 2nd edition of this book, and I only found the 1st edition in a quick search. Nonetheless, I can say with certainty that (in the 1st edition, at least), Brewester never mentions dog urine or Mr. Phelps.

It seems odd that Land would completely fabricate the dog urine story, and stranger still that he would cook up a name for Herapath’s student, yet the sources that Land cites simply don’t support either of these two details. Very odd!

Thanks for your investigative work.