Some technology is so pervasive and mundane in modern society that it is hard to comprehend what a seismic shift its introduction caused in civilization. Examples I can think of are refrigerators and air conditioning, but in science an example that I hadn’t really appreciated until recently is the humble polarizer — in particular, the inexpensive sheet polarizers that form the basis for almost every practical polarizer used today.

Not long ago I wrote a blog post about the curious history of the crystal herapathite, one of the first truly effective polarizing materials. It was discovered in 1852 by accident, but didn’t really become a practical polarizing material for some 75 years, mainly due to the extreme difficulty in growing crystals large enough to be used for optical devices. In 1929, however, Edwin Land took a very different strategy: he used a magnetic field to align a solution of microscopic herapathite crystals, and then dipped a sheet of plastic into the solution to capture the crystals. The result was a thin material that produced nearly perfect polarization over the entire visible spectrum of light, and one that could be produced in large quantities inexpensively. This material, dubbed Polaroid, become the basis of the Polaroid company that later created the Polaroid instant camera (no relation to polarizers).

How big a deal was the creation of Polaroid? Well, in 1938 an article appeared in the Journal of Applied Physics titled, “Polarized light enters the world of everyday life.” The purpose of the article was the lay out all the new technologies, and possible technologies, that could now be implemented thanks to Polaroid and similar polarizers. In this blog post, I thought I would give an overview of this paper and the applications it covered, to show how inexpensive mundane polarizers really did change the world!

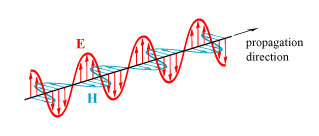

To begin, though, let me again give a brief explanation of polarization and the types of polarizers that existed before Polaroid. Thanks to the work of James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s, we know that light is a transverse electromagnetic wave. By “electromagnetic wave,” we mean that it is the electric and magnetic fields doing the waving, and by “transverse,” we mean that those fields wave perpendicular to the direction the wave is travelling. A simple illustration of such a wave is shown below.

The E in this figure refers to the electric field, and H refers to the magnetic field. In this figure, where the wave is going into the page, the electric field is waving up-down and the magnetic field is waving left-right.

Because light is a transverse wave, there are always two possible directions for light to wave for any given direction of light propagation. In the case above, we could also draw a wave where the electric field is waving left-right and the magnetic field is waving up-down. If a light wave consists solely of light waving in one transverse direction, as in the figure above, it is said to be polarized.

Natural light sources like the sun, light bulbs and candles, however, produce light that is unpolarized — the light that is generated is a random rapid mixture of, say, up-down and left-right oscillations of the electric field. If you want to generate polarized light from a natural light source, you need some sort of device that will block one set of oscillations, say up-down, and allow the other set, say left-right, to travel on.

Early in the 1800s, soon after the discovery of light polarization, a number of methods were devised to polarize a light wave. One of these is to reflect light off of a glass surface at a special angle called the Brewster angle. At that special angle, all of the vertically polarized light is transmitted into the glass without reflection, leaving only horizontally polarized light.

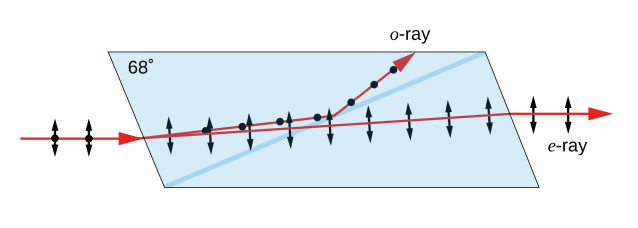

Another method is to use a device known as a Nicol prism, as illustrated below via Wikipedia.

The Nicol prism takes advantage of two optical phenomena: birefringence and total internal reflection. Birefringence is the phenomenon in which certain crystals, like optical calcite, will refract light differently for the two polarizations. This is illustrated by the light going into the prism dividing into two separate, perpendicularly polarized, beams. The prism is divided into two pieces separated by a low refractive index glue. The o-ray (ordinary ray) gets refracted beyond the angle for total internal reflection, meaning all the light at that polarization gets reflected out of the crystal, leaving the polarized e-ray (extraordinary ray).

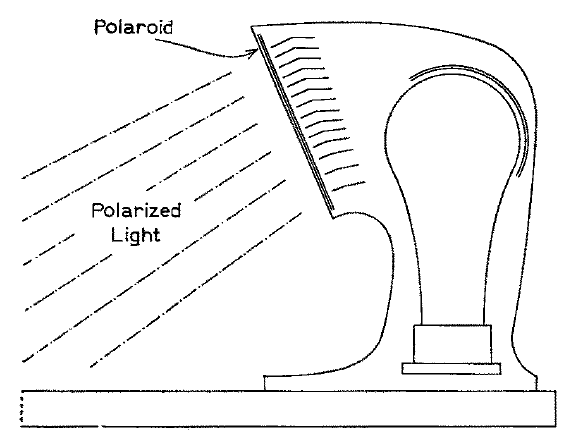

Both of these techniques are limited in that they tend to be wasteful of light — even the desired polarized light gets significantly reflected — and the Nicol prism tends to be costly and difficult to scale up to larger sizes for applications. A third option, which was also discovered in the early 1800s, is the use of natural crystals that strongly absorb one polarization of light and let the other polarization pass through (the illustration from the paper we’ll be talking about is shown below). Tourmaline was the most commonly used crystal, but it is very color selective, only working as a good polarizer for a limited range of colors (wavelengths). Also, tourmaline tends to be inefficient in that is also significantly absorbs the polarization you want to keep!

So polarizers tended to be expensive, inefficient, and difficult to scale up in size. The development of inexpensive sheet polarizers in the early 1900s changed the game and the possibilities dramatically. Three types were independently discovered: Polaroid, the Marks plates, and the Zeiss Bernotar filters. The Zeiss Bernotar filters are large single crystals of herapathite, grown using a process discovered by Ferdinand Bernauer. The Marks plates are arrangements of smaller crystals of herapathite painstakingly arranged to form a single polarizer. Neither of these competitors could match the ease of manufacture of Polaroid films, however, which quickly became the polarizer of choice.

So what applications exist for inexpensive polarizers? Now we turn to the paper by Grabau. The first application he mentions is a commercial product: the Polaroid desk lamp. Recalling our discussion of the Brewster angle, it turns out in general that most of the light that gets directly reflected from a surface is horizontally polarized. If one is looking at a sheet of glossy paper, one will get a glare from the light that is directly reflected off of the glossy surface, which is primarily horizontally polarized. If a polarized is used on a lamp to block that polarization, then the glare will be substantially reduced! The illustration from the paper is below.

The odd shape of the lamp in the image is not just due to poor drawing: the actual Polaroid lamps had a very unusual shape. Here’s an image of a vintage one from the Brooklyn Museum; I’ve seen used ones online for sale for $4500!

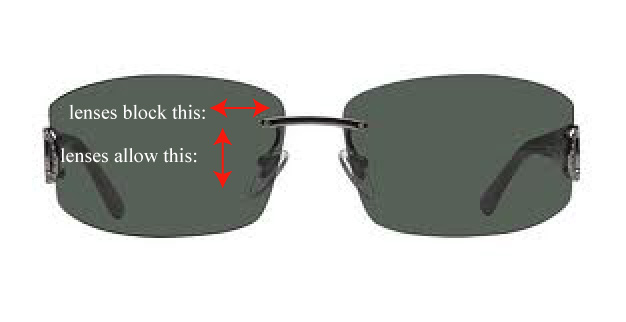

Polarized desk lamps do not seem to have endured as a popular product, but another use of polarizers for glare reduction has: polarized sunglasses! As described by Grabau,

Almost all the glare seen on bright days originates in reflections of sunlight from such horizontal mat surfaces as sidewalks, street pavements, etc. This glare-light is predominantly polarized in the horizontal plane. Sunlight reflected from the sea, ice, and glazed snow is similarly affected. A pair of polarizing spectacles, with vertical polarizing axes, quenches the glare very considerably and creates a freedom from ocular fatigue that is difficult to describe.

I’ve talked about this application in an earlier blog post; my illustration of how polarized sunglasses work is given below.

The glare reduction for polarized sunglasses can be quite significant; here is a video I once did from my office showing how glare can be mostly eliminated with a polarizer.

Grabau notes that this application can be applied to all sorts of optical devices, particularly ones used in ocean voyages,

The use of spyglasses and sextants at sea has always been attended by the disturbing glare of sunlight reflected from the water. Hulburt has observed the high percentage polarization of this glare-light and shown how it can be quenched with suitably oriented polarizing filters.

Another optical device mentioned by Grabau still takes advantage of polarizers to this day: cameras. As Grabau states,

In scenes to be photographed, there is often a certain surface reflection that creates a disturbing highlight; and over quite a large range of angles, this light will have undergone considerable polarization. A polarizing filter over the camera lens brings such a highlight under control, more or less independently of the rest of the picture, and makes it possible to bring out the detail of the picture over a wide range of intensities, as it were to circumvent the relatively short latitude of the photographic emulsion.

An image is included to show what the photograph of a storefront looks like without and with an appropriate polarizer. Though it is an old grainy photo, one can see that the reflections are largely suppressed on the right.

This is still a technique used today; here is a website that talks about using a circular polarizer filter for taking photos of museum pieces that are often behind pesky glare-heavy glass.

Speaking of museums, Grabau suggests that art museums could illuminate their artwork with polarized light directly, so that the glare of the light on the varnish is eliminated and the artwork shows through. I don’t know if this is actually done anywhere, but it is an interesting idea.

Another idea that I find quite intriguing but which didn’t take off: polarized headlights! The idea is illustrated below, taken from the paper. Suppose every car has headlights that are polarized (from the perspective of the driver) up and to the right, and also has a polarizing film on their windshield with the same orientation. Then most of the light reflected from objects like the bicyclist will have the same polarization and be seen, while the headlights of the oncoming car will be perpendicularly polarized and blocked.

This seems like a clever idea but one that obviously wasn’t applied. I suspect that the idea is great in principle, but in practice the glare reduction isn’t worth the amount of light lost passing through the polarizer overall.

Polarizers can produce some surprising and even beautiful effects, and these can form the basis of other applications. One curious possibility is the use of polarizers and birefringent material (like the calcite of a Nicol prism) to create vivid colors for advertising displays. As Grabau says,

\Vhen a sheet of birefringent material (mica, Cellophane, cellulose tape, etc.) is inserted between two polarizing sheets, the ensemble becomes a color filter whose color may be varied by rotating one of the polarizing sheets or by tipping or changing the thickness of the birefringent sheet. This is an important new method of producing color in general illumination and advertising displays, and it may even find architectural applications, if the current trend toward the use of translucent building materials persists.

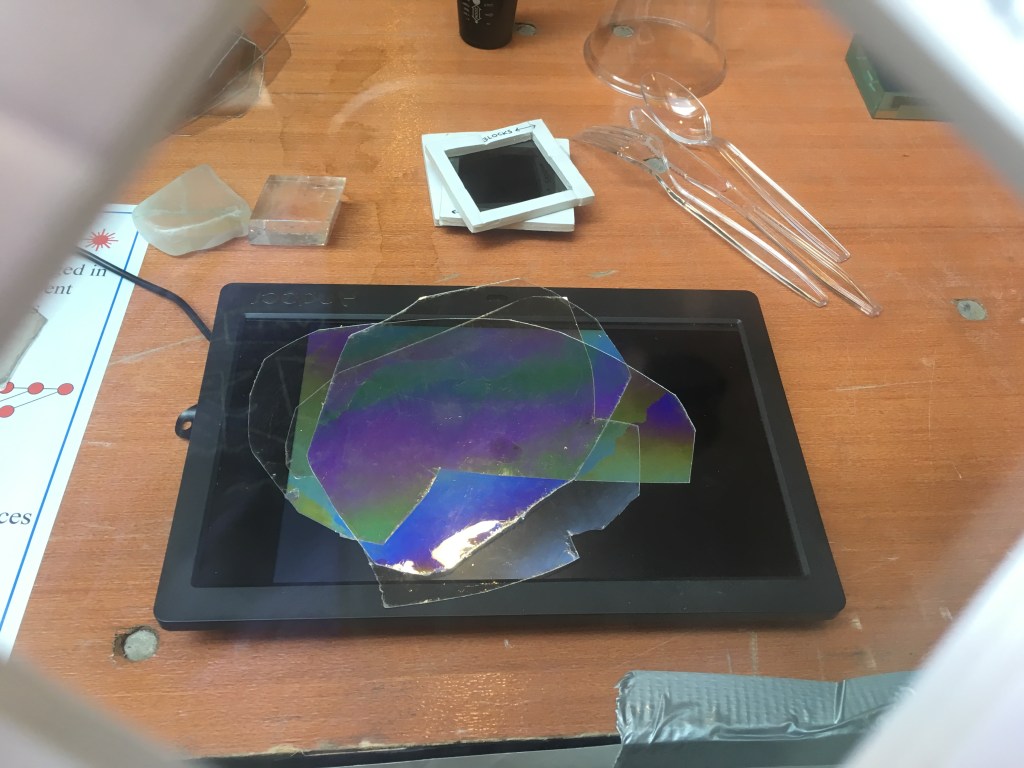

To give an idea of how this would work, here’s an old photo I took of some birefringent mica between crossed polarizers. The LCD screen produces polarized light to begin with, and I took the photo of the mica through a polarizer oriented perpendicularly.

The mica itself in natural light is of a very bland color, but when one looks at it through polarizers one gets extremely vibrant colors. It is this sort of approach that Grabau suggests for making new and eye-catching advertising displays; again, I’m not sure if this was ever implemented.

Incidentally, if the polarizers are crossed, how do we see any colors at all? The mica changes the state of polarization of light passing through it — if it was vertical going into the mica, it comes out with a mix of vertical and horizontal, and a crossed polarizer will allow the horizontal light to pass. Different colors will experience this birefringent effect differently, overall giving a beautiful color pattern.

This same effect can be put to industrial use, in looking for hidden stresses in materials. I’ll let Grabau explain this one:

Whenever ordinary transparent materials (glass or certain plastics) are subjected to stresses, the strained regions inside are characterized by changes in their optical properties whereby they become temporarily birefringent. The amount of birefringence produced at any point in the material is in part a measure of the strains existing there. Consequently, when a strained sample is inserted between crossed polarizers, light is restored in the regions under strain. This restored light usually appears in the form of variously colored striations; and from the shape, spacing, and color of these striations, it is possible to identify the distribution of stress in the sample. This is the technique of photoelasticity.

In other words, stressed parts of transparent materials become birefringent, and we can see those stresses through crossed polarizers! This is another really fun thing to demonstrate for onself; the image below is of some transparent plastic silverware that I imaged a few years ago.

All the sharp variations of color are giving an indication of where the stresses in the molded plastic are: it can be seen especially prominent near the base of the fork tines. This process is still used in industry to this day; here is an image from Grabau’s paper showing an industrial strain tester in use. The worker is wearing polarized glasses and looking at a bottle illuminated by polarized light.

Because birefringent materials cause changes in the polarization of light, one can in reverse use polarization effects to learn about the structure of birefringent materials. Grabau mentions using a microscope with a polarizing filter to study crystals, textile fibers, and rock sections.

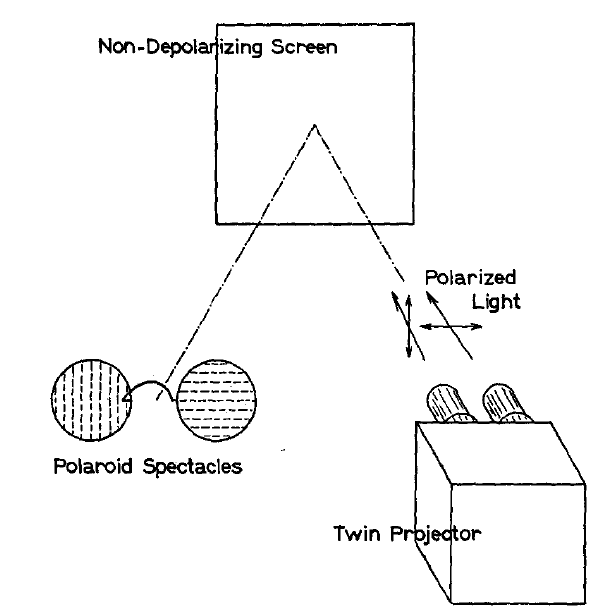

Let us highlight one more well-known application of polarization filters that Grabau mentioned: 3-D images! I let Grabau take the lead here again:

In order to project stereoscopic pictures on a screen, it is only necessary that there shall be a stereoscopic pair of pictures, one to be seen by the right eye and the other by the left. With polarized light this is accomplished very simply.

… The two pictures are projected on a nondepolarizing screen, the light of the one being

polarized at right angles to that of the other. The viewer wears polarizing spectacles, with the axes of the two polarizing “lenses” appropriately oriented and at right angles to each other to admit to each eye the image intended for it.

In other words, one uses two projectors, each projecting a polarized image, and then the viewer wears polarized glasses which allow only one image into each eye, allowing for three-dimensional images. Grabau’s picture of this is shown below.

Curiously, Grabau seems to only mention still images in his description, leaving out the obvious leap that the same approach can be used to make 3-D movies, and in fact this is how 3-D movies are done today! The only difference in modern 3-D movies is that the two projected images use left- and right- circular polarization, instead of left-right and up-down linear polarization. 3-D glasses that filter circular polarization are then worn by the person watching the movie.

This seems like a particularly odd omission because 3-D movies were already in use in Grabau’s era! The first 3-D movie, The Power of Love, was shown in 1922, and it used the classic red-green image and glasses to produce the 3-D effect. Wikipedia shines some light on why polarization wasn’t considered in that early era: to maintain the polarization effect, the movie must be projected on a smooth reflective screen, something that movie theaters did not have. Nevertheless, the first polarization-based 3-D film, In Tune with Tomorrow, was shown at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and 3-D Polaroid movies became common after that.

The great advantage of using polarization instead of color to make 3-D movies is that the movies can be filmed and projected with their natural colors. Or, as Grabau says of the still images he talks about,

This method is the only one known to project stereoscopic pictures in natural colors. It may also be adapted to the construction of stationary viewing devices for stereoscopic pictures in museums, schools, etc.

So, with the invention of Polaroid film, polarization went from being a quite difficult and exotic phenomenon to being an everyday one! We are all aware that technology can radically transform our lives, but it is interesting to see how a very simple and elementary advance like an inexpensive, easy to make polarizer can have a huge impact.

***********************************************

- Martin Grabau, “Polarized light enters the world of everyday life,” J. Appl. Phys. 9 (1938), 215.

A fun and fascinating exploration, thanks!

That was a particularly fun and fascinating exploration. Thanks!