Some time ago, I was browsing 150 year old popular science magazines as one does and I found an amusing editorial from 1879 in The Popular Science Monthly titled “Explanations that do not explain.” The unsigned editorial discussed a recent lecture by the famed William Thomson aka Lord Kelvin that itself was titled “Maxwell’s Sorting Demons.”

“Maxwell’s demon” is a famous thought experiment first introduced by the groundbreaking physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1867 and which still provokes thoughtful discussions and controversy to this day. The funny thing about the editorial in Popular Science Monthly is that the editor/editors clearly did not understand the point of Maxwell’s argument and seem genuinely angry that it was introduced at all! To me, this is comparable to, albeit not quite as bad, as the infamous 1920 NYT editorial that claimed that it is impossible for rockets to fly in space! (The NYT posted a correction some 50 years later, as astronauts were on their way to the moon.)

I’ve recently been brushing up on my thermodynamics, and this all seems like a good opportunity for me to explain a little bit of the subject and how Maxwell’s demon has played a noteworthy role in trying to understand some truly fundamental physics. It’s good practice for me, though I will stress that I’m still brushing up so I might make some goofs along the way — hopefully not! We’ll wrap up by talking about the angry letter of Popular Science Monthly.

This post is quite long, because I cover a lot of background material, so I have separated it into different sections for easy reading over several sessions, if needed.

I. What is Thermodynamics?

First of all: what is thermodynamics? To quote from Britannica, thermodynamics is the “science of the relationship between heat, work, temperature, and energy.” Basically, any time you are studying a system where heat and temperature play a role, the principles of thermodynamics come into play. This includes things like understanding how steam engines work, how air conditioning and refrigeration work, and how heat flows from a hot object to a cold object, like a cold drink warming up on a hot summer day.

We know today that heat is simply a manifestation of the random motion of atoms and molecules, and the study of thermodynamics is the study of large systems of particles whose behavior can only be quantified by calculating the average properties of the collection as a whole. This makes the subject quite a shock to physics students when they encounter it for the first time, because definite concepts like “velocity,” “force,” and “momentum” of individual particles get replaced by more abstract concepts like “temperature” and “entropy” of large collections of particles (we will talk about more about entropy momentarily). The history of the subject also doesn’t help its clarity: the foundations of thermodynamics arose in the early 1800s as researchers sought to optimize steam-powered engines. In that era, the concept of energy had not yet even been introduced (and I have some posts on that history). Furthermore, the consensus view on heat at the time was that it was a material fluid called “caloric.” I feel that part of the difficulty in learning thermodynamics comes from how it evolved during a time of great confusion in physics.

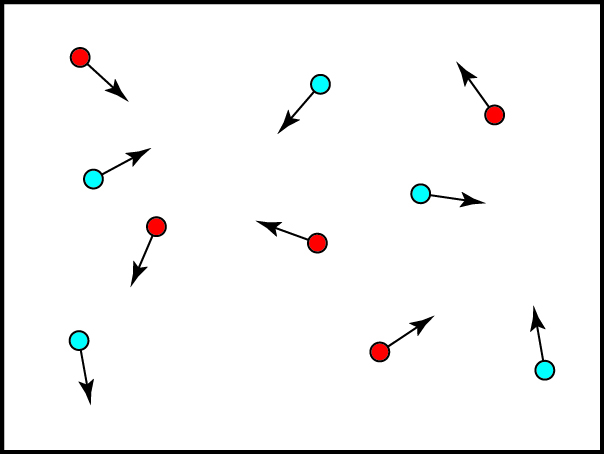

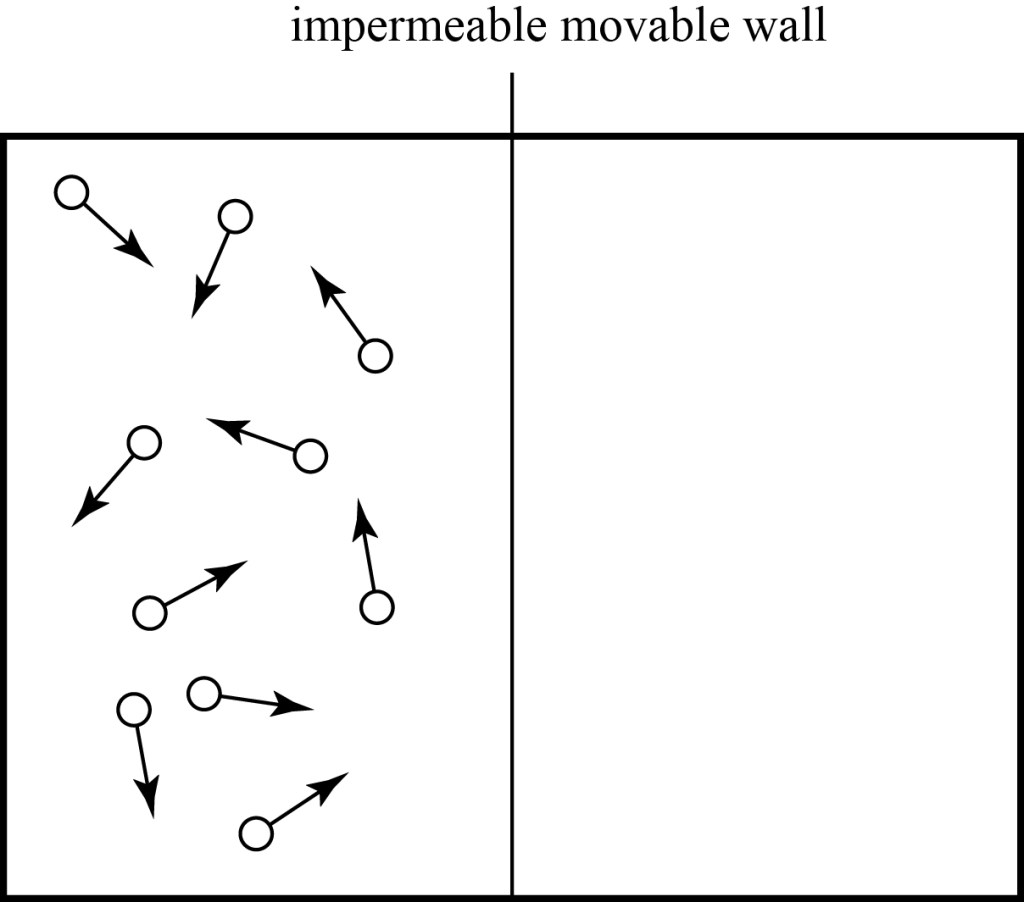

To reduce some confusion, let’s focus on one specific thermodynamic system — an ideal gas contained in a box. For simplicity, we’ll often use a box with just ten particles, as shown below. Of course, real gases have a much, much larger number of particles. One mole of gas at standard temperature and pressure, which fills 22.4 liters, is particles! That’s a lot.

The arrows indicate the directions that the particles are moving and, for illustration purposes, faster (“hotter”) particles are shown in red and slower (“colder”) particles are shown in blue. In an ideal gas, all particles are identical and have negligible interactions with each other outside of occasional collisions. We will also assume that the box is thermally insulated, so no energy leaks in or out. The result is a bunch of particles bouncing around endlessly, without any change on average of the overall behavior of the system: if we measured the temperature in the box, or the pressure of the gas, we would find it unchanging over time. In this case, we say that the system is in thermal equilibrium: it is in a stable thermodynamic state.

Following the example of Isaac Newton, who introduced his three laws of motion as the foundation of classical mechanics, researchers worked to introduce foundational laws for thermodynamics. The three that will concern us here are the Zeroth Law, the First Law, and the Second Law; let’s look at them in turn. It should be noted that the First and Second Laws in particular were formulated and reformulated multiple times while people were trying to figure out how thermodynamics actually works, so there are multiple statements of these laws. These different statements are for the most part equivalent to each other, but some are more useful than others in analyzing specific problems.

Zeroth Law. If systems A and B are in thermal equilibrium, and systems B and C are in thermal equilibrium, then systems A and C are in thermal equilibrium.

This law is in essence a very formal way to define the concept of temperature. If the zeroth law holds, then one can show that there must be a quantity whose value is the same for all three systems, and this quantity is what we associate with temperature (and which agrees with our definition of temperature for familiar systems like an ideal gas). If two systems with the same temperature are brought together, there is no net heat flow between them.

Why does it have the curious name “zeroth law”? My understanding: long after the first and second laws were established, researchers recognized that they really needed a law that defines temperature in a way that is independent of any particular type of system. Such a definition should be introduced before talking about any other thermodynamic principles, so it got pushed to the front of the line and became the “zeroth law.”

First Law. Energy is conserved in a thermodynamic system. If Q represents the heat flow into a system, and W represents the work done on a system, then the change in energy U of the system is U = Q+W.

“Work” in this case refers to mechanical work done to/done by a thermodynamic system. For an ideal gas, for example, changing the volume of the gas involves work. If we compress the gas, we are pushing against the pressure of the gas and the energy of our effort gets transferred into the gas; if we let a gas expand freely, for example by pushing against a wall that is free to move, then the gas itself is doing work and transfers energy to another system. The latter case is basically how heat engines work — the pressure of a hot gas is used to push something else.

It may seem odd to define conservation of energy as its own thermodynamic-specific law, since it is a general law of physics. However, we again note that energy conservation was discovered in the context of studying thermodynamics, and it was immediately recognized that it was key to understanding heat and thermal systems. Thermodynamics was the first physical theory introduced where energy conservation is absolutely essential. In problems of forces and motion, for example, researchers had previously gotten along just fine using Newton’s laws. The first law also defines heat as a type of energy transfer: if we heat up an object, we are adding energy to it.

Now we come to the big one, the Second Law. We start by using the statement given by Rudolf Clausius:

Second Law. Heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

This law in essence argues that heat always flows the way we think it does. If you heat up a cup of coffee and put it on the counter, the heat will always flow away from the cup and into the colder air and countertop. The coffee will never become spontaneously hotter while the air and countertop become even colder. We can, of course, make something colder — that’s what air conditioning and refrigerators are for — but we have to do “some other change,” namely work. If we want to cool something down, we have to expend energy to do so, and the result is a lot of extra lost energy in the form of heat. This is why, for example, an air conditioner (like a window mounted A/C) must have an output to the outside — in the process of cooling it produces extra heat that has to be funneled away.

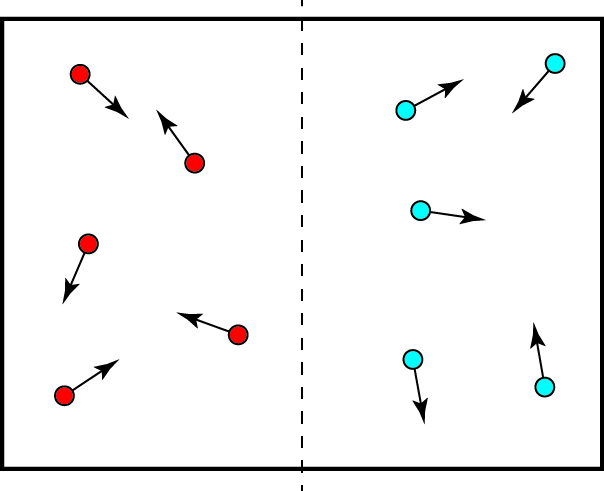

The Second Law is, curiously, completely independent of the First Law. Conservation of energy by itself tells us nothing about why heat flows the way it does, and heat flowing from cooler to hotter objects is perfectly consistent with it. To understand why the Second Law exists, let’s look at our box of ten particles again, but start by assuming that all the hot particles are in the left half of the box and all the cold particles in the right half:

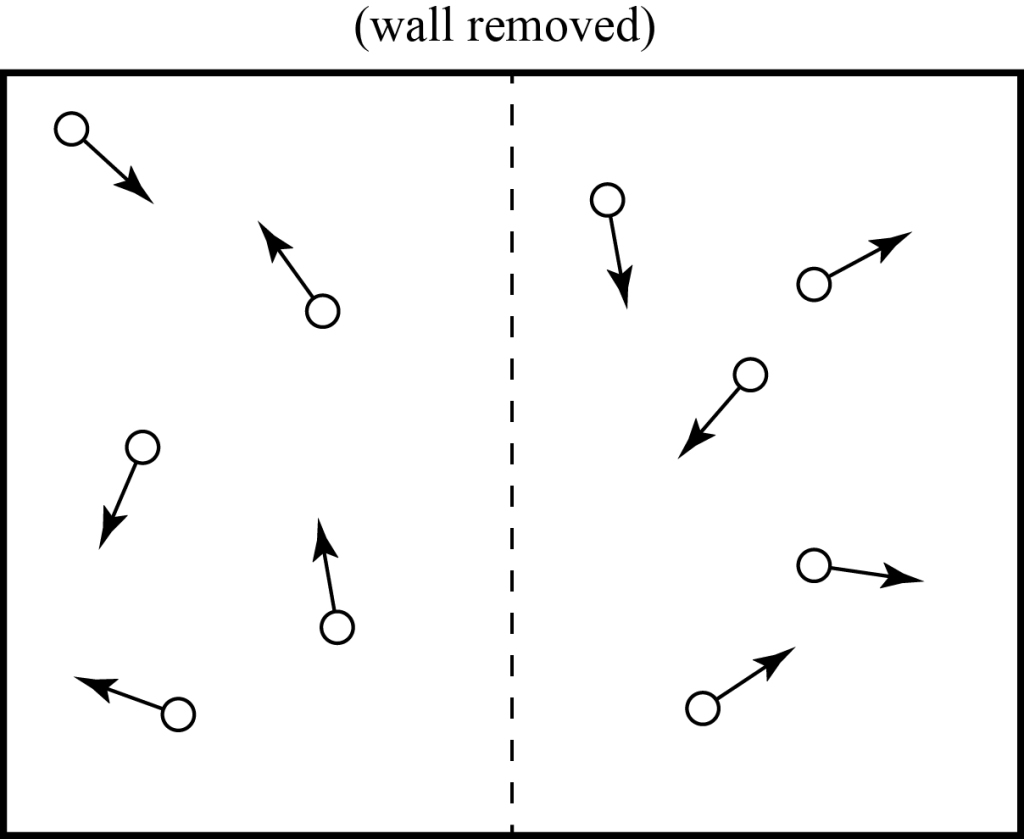

If at this instant we were to take the temperature of the two halves of the box, we would find that the left side has a higher temperature than the right, because the particles on the left have more energy than those on the right. As time passes, however, all the particles will bounce around in the box, and each particle will typically spend 50% of its time in the left side of the box and 50% of its time in the right side. We will therefore find that each half of the box will have on average the same number of particles, and the same number of hot and cold particles. If we take the temperature of the two halves of the box after some time, we’ll find that the side of the box that was originally hot is now cooler, and the side of the box that was originally cold is now warmer, and they have the same temperature — they’re at thermal equilibrium. The heat has “flowed” from the hotter region to the colder region.

II. The Second Law and Entropy.

Clausius’ statement of the Second Law is a bit limited, however. We can introduce systems where heat doesn’t play a direct role but our explanation of “flow” still applies. For example, let’s consider a box of ten particles which all have the same speed, but we start by having them all confined to one half of the box by an impermeable wall that we can quickly remove when we want.

What happens when we remove the wall? We expect that the particles will quickly expand into the full volume and, like our earlier example, we’ll eventually find that each half of the box typically contains one half of the particles.

This example is spiritually very much the same as our previous example, except it only concerns the flow of particles, and we would like a statement of the Second Law that incorporates situations like this and gets away from talking only about heat flow. This leads us to a statement of the Second Law in terms of entropy:

Second Law (modern). The entropy of a closed system always increases in time until it reaches a maximum value.

We need to spend some time talking about entropy, but first let’s define what we mean by a “closed system.” For our purposes, a closed system is one that is isolated from the outside world, without energy or matter coming in or out; a fair example is our box of particles, which we have said is thermally insulated. Entropy can be “carried off” by matter or energy leaving a system, so the Second Law becomes meaningless unless we restrict ourselves to closed systems. An example of a non-closed system would be a room cooled by an air conditioner: temperature in the room itself is going down, and the entropy of the gas in the room is decreasing, but this drop in entropy is balanced by a greater increase in entropy from the heat generated by the A/C itself, which is sent outside the room.

The entire universe itself may be considered a closed system, resulting in the often used phrase “the entropy of the universe is always increasing.”

So what is entropy? It first appeared in early thermodynamics research and is well-defined there, but we will consider instead the modern, equivalent, definition that is based on the possible behaviors of the particles of our system.

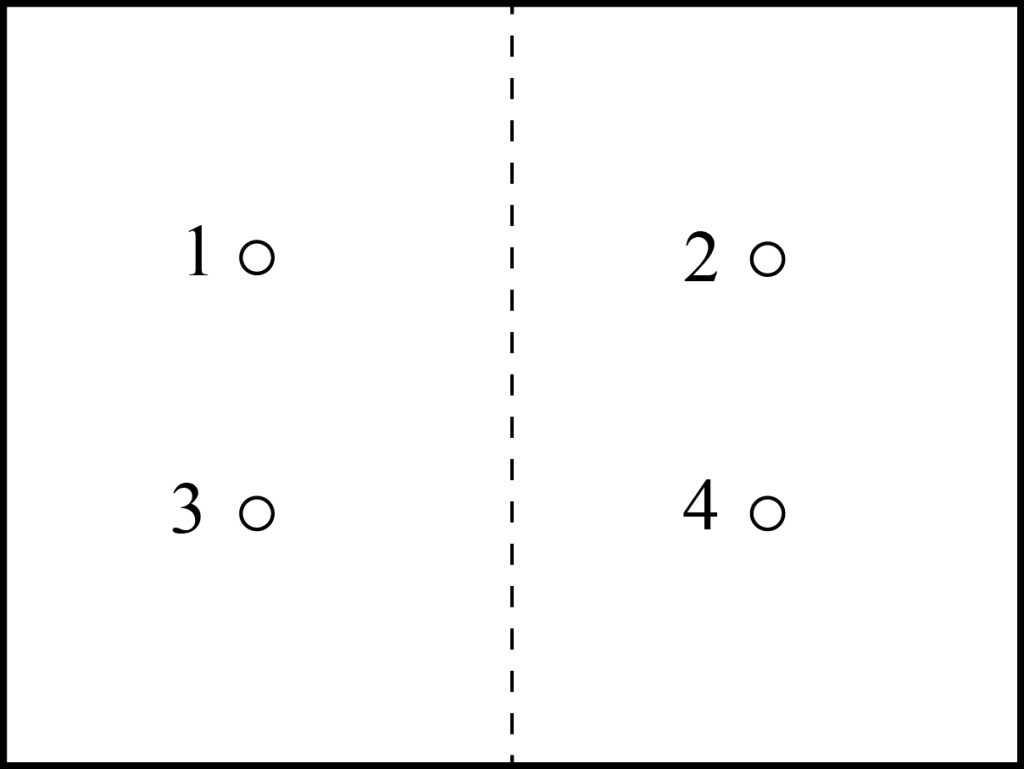

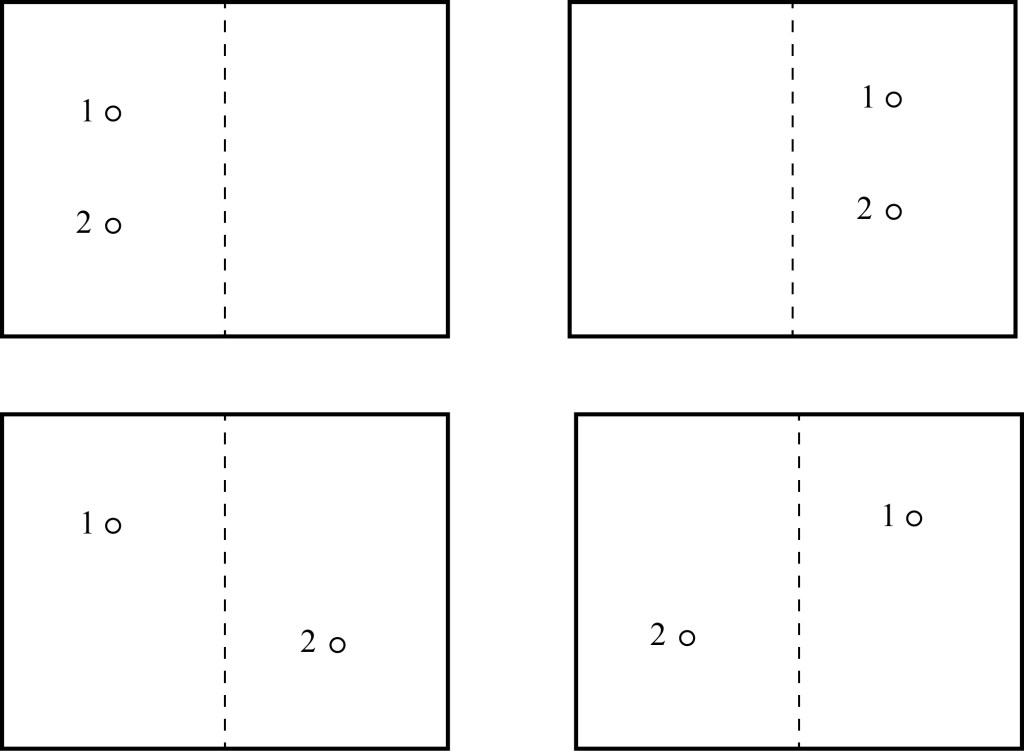

Let’s look at our box of particles again, but only consider four particles, and we’ll label these particles 1,2,3,4. To make things simple, we consider only two possible states for each particle: it can be in the left side of the box or the right side of the box. So one possible state has two particles in each side of the box, as shown below:

When we simply specify how many particles are in each side of the box, we are specifying the macrostate of the system. The macrostate is the observable state that can be measured by an experimenter. But we should note that we can get the same macrostate with some of the particles in different locations if those particles are essentially identical, e.g. with particles 2 and 3 switching sides:

When we specify which particular particles are where, we are talking about the microstate of the system (we are looking at the microscopic behavior of the individual particles). The simple example above shows that there are typically multiple microstates for every macrostate.

Let’s consider each macrostate in turn, starting with the one with all four particles on one side. There is a single microstate for each of these macrostates:

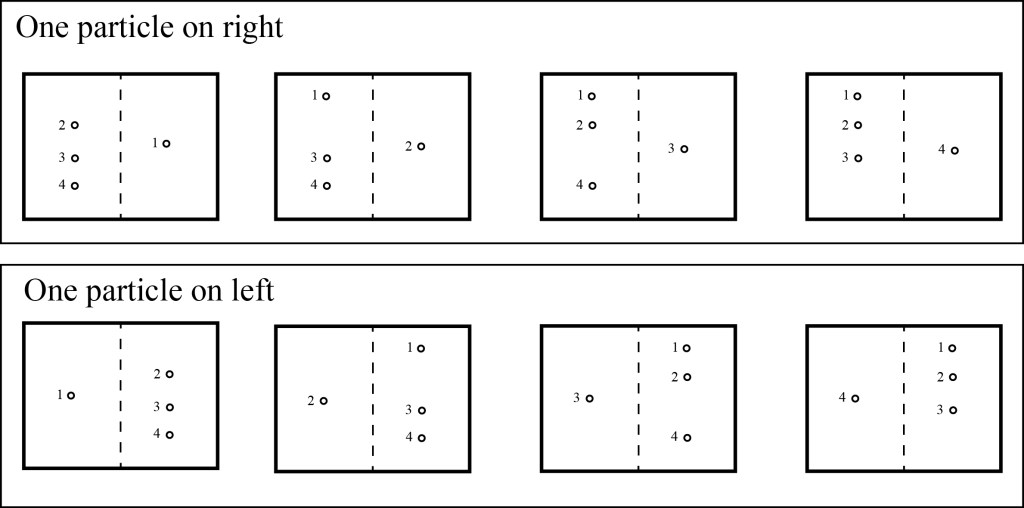

What if we consider the cases where there’s a single particle on each side? Now there are four possible options, i.e. four microstates, for each macrostate:

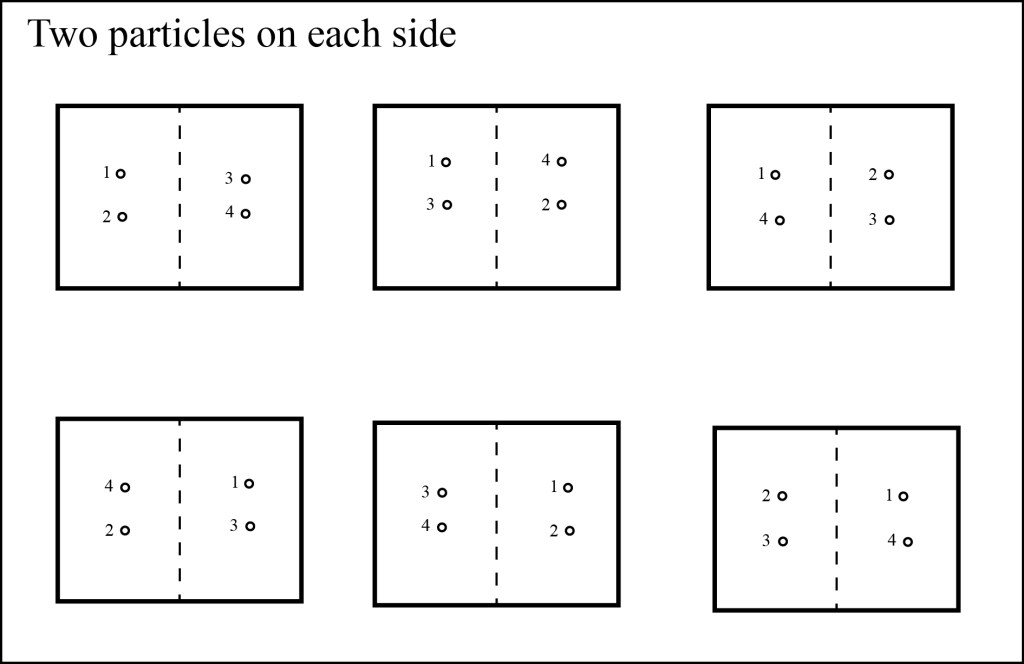

What about the macrostate where there are two particles on each side? Here, we have six possible microstates:

If we consider all possible microstates, there are two possible positions for each particle, so there are 24 = 16 microstates, which is the total number of all the figures above.

Now, if we were to throw all the particles into the box at random, what is the most likely macrostate? In 6 out of 16 times, we’ll end up with two particles on each side, while we will end up with all four particles on the left side only 1 in 16 times. This difference in probabilities gets even more extreme when we add more particles: for a box with ten particles, we’ll have the particles equally split 252 out of 1024 times, while we’ll have all ten particles on the left side only 1 out of 1024 times. If we increase the number of particles to 1000, we’ll find that almost all of the time we’ll have the particles evenly divided, or close to evenly divided, and we’ll pretty much never have all the particles in one side of the box. If we increase the number of particles to a realistic number for a gas like we can safely say that the particles are always extremely close to evenly divided.

This is a probability version of the arguments we made in our previous two examples, of hot and cold particles in a box and a bunch of particles in one side of a box. Just by randomly bouncing around, the particles are going to end up in the most likely macrostate — one where all the heat or all the particles are evenly divided up. The flow of heat, and the diffusion of gas, can be said to be less a physics principle and more of a numbers game.

This brings us back to entropy. The entropy of a given macrostate is directly related to the number of related microstates (in fact, it is proportional to the natural logarithm of the number of microstates). Thus, when our particles spread from one side of a box to fill the box, the number of microstates increases and the entropy increases. The increase of entropy can be said to be the system settling on the most likely macrostate under the current conditions.

This whole discussion of entropy and probabilities was done to make an important point relevant to Maxwell’s demon: the Second Law of Thermodynamics is not an absolute law, but a law involving probabilities. It doesn’t say that it is impossible for all the particles in a box to end up on one side of the box spontaneously, it just says that it is extremely, stunningly unlikely that this would ever happen. This makes the Second Law very different from every other physical law you might be familiar with. The First Law of Thermodynamics, for example, says that energy is conserved — period — not that it is merely likely to be conserved!

The probabilistic nature of the Second Law is something that makes physicists uncomfortable, and leads to a number of conundrums. First, we can note that, as we have defined it, the entropy is never at a “maximum” at all times. Suppose we have 1000 particles in a box, where each particle can be either on the left of the right. The maximum entropy state is with 500 particles on a side, but it should be clear that there will likely be moments when there are 501 on one side and 499 on the other, just due to random fluctuations, and the entropy as defined in that situation is less than maximum. Apparently the best we can really say is that on average the entropy is close to maximum.

This argument gets even more absurd if we consider a system with only two particles. Then there are four states total, one with both particles on the left, one with both particles on the right, and two with one particle on each side:

If we assume our two particles are randomly bouncing around, then 50% of the time we expect one particle on each side, but a lot of the time — 50% of it — there will be both particles on one side or the other. You might object that thermodynamics isn’t intended to be used for small systems of particles, only large systems of particles, but that means we have to add a caveat to our definition of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: “only true for systems of particles beyond a number of particles that we will arbitrarily define.”

At this point, discussions of the Second Law start to sound a bit like this:

This problem, incidentally, is not too different than issues that arise in quantum physics. We can all agree that quantum physics applies for objects that are really small, and classical physics applies to objects that are really big, but where is the dividing line — what size is “too big” for quantum physics? There isn’t a good answer for this question, and in fact researchers have spent years demonstrating quantum effects for larger and larger objects. Back in 1999, researchers experimentally demonstrated quantum interference for carbon-60 molecules, which are 60 carbon molecules bound together!

Before moving on, we should stress that the Second Law of Thermodynamics works perfectly well for all practical problems known! The concerns that we mention above, like the concerns in quantum physics, are more philosophical than practical. Maxwell’s demon, however, changes this significantly.

III. Maxwell’s Demon.

James Clerk Maxwell was probably the greatest theoretical genius of his time in physics. In 1865, he published his most famous result, showing that completed equations for electricity and magnetism predict electromagnetic waves traveling at the speed of light, and that this suggests that light is an electromagnetic wave. The complete set of equations became known as Maxwell’s equations.

Maxwell had also established himself as a leading theorist in thermodynamics, and so when Peter Guthrie Tait was preparing a book on the subject, he wrote to Maxwell for insights. Maxwell’s response was the first introduction of what is now known as “Maxwell’s demon.”

Let me first describe the “demon” in my own words, then for fun I’ll include Maxwell’s original description. In Clausius’ formulation of the Second Law, we have seen that heat will not flow from a cold region to a hot region in the absence of external work; however, we have also seen that this is not something that is strictly forbidden, but is a probabilistic law.

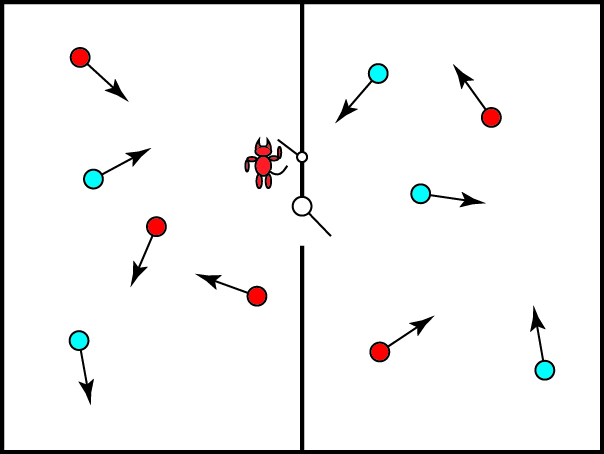

Maxwell recognized the probabilistic hole in the law and reasoned around it as such: let us again consider our box of gas, with a dividing wall separating the gas into two halves, and the two halves of the gas are at the same temperature (in our simple model, with equal numbers of fast and slow particles in each). We imagine a tiny door is situated in the dividing wall, and that it can be easily opened and closed at will by a small being — the demon — who serves as a doorman of sorts.

Now the demon simply observes the gas molecules and normally keeps the door closed. If it sees a fast (hot) particle coming from the left, however, it opens the door, and if it sees a slow (cold) particle coming from the right, it opens the door. The result, after some time, is that the particles on the right of the box are hotter than those on the left!

This is a lower entropy state, so that we can say that the demon has reduced the entropy of the system without doing work on the gas. It is important to note that “work on the gas” conventionally refers to applying pressure to the gas, e.g. by pressing on one wall of the box. Here, the demon has not directly touched or interacted with the gas molecules at all, and has simply facilitated the self-sorting of the gas molecules. Maxwell further imposes the constraint that the demon itself does no work, and only opens or closes frictionless valves to allow the door to be opened or closed. Even if the demon does work in these operations, in principle it appears that effort could be made arbitrarily small.

We can introduce two types of demons, in fact: one that sorts particles by temperature, as shown above, can be called a “temperature demon.” One that simply moves as many particles as possible from, say, the left of the box to the right of the box can be called a “pressure demon.”

Here’s how Maxwell himself introduced1 the “demon”:

I do not know in a controversial manner the history of thermodynamics, that is, I could make no assertions about the priority of authors without referring to their actual works…. Any contributions I could make to that study are in the way of altering the point of view here and there for clearness or variety, and picking holes here and there to ensure strength and stability.

As for instance I think that you might make something of the theory of the absolute scale of temperature by reasoning pretty loud about it and paying it due honour at its entrance. To pick a hole — say in the 2nd law of

cs., that if two things are in contact the hotter cannot take heat from the colder without external agency.

Now let A and B be two vessels divided by a diaphragm and let them contain elastic molecules in a state of agitation which strike each other and the sides.

Let the number of particles be equal in A and B but let those in A have the greatest energy of motion. Then even if all the molecules in A have equal velocities, if oblique collisions occur between them their velocities will become unequal, and I have shown that there will be velocities of all magnitudes in A and the same in B, only the sum of the squares of the velocities is greater in A than in B.

When a molecule is reflected from the fixed diaphragm CD no work is lost or gained.

If the molecule instead of being reflected were allowed to go through a hole in CD no work would be lost or gained, only its energy would be transferred from the one vessel to the other.

Now conceive a finite being who knows the paths and velocities of all the molecules by simple inspection but who can do no work except open and close a hole in the diaphragm by means of a slide without mass.

Let him first observe the molecules in A and when he sees one coming the square of whose velocity is less than the mean sq. vel. of the molecules in B let him open the hole and let it go into B. Next let him watch for a molecule of B, the square of whose velocity is greater than the mean sq. vel. in A, and when it comes to the hole let him draw the slide and let it go into A, keeping the slide shut for all other molecules.

Then the number of molecules in A and B are the same as at first, but the energy in A is increased and that in B diminished, that is, the hot system has got hotter and the cold colder and yet no work has been done, only the intelligence of a very observant and neat-fingered being has been employed.

Or in short if heat is the motion of finite portions of matter and if we can apply tools to such portions of matter so as to deal with them separately, then we can take advantage of the different motion of different proportions to restore a uniformly hot system to unequal temperatures or to motions of large masses.

Only we can’t, not being clever enough.

Two things stand out in this passage. First, we note that nowhere does Maxwell, refer to a “demon,” only a “finite being.” Maxwell’s point is that this experiment could in principle be done without a being of omnipotent power. The term “demon” was actually coined by Lord Kelvin in an 1874 paper2, though he really meant “daemon,” referring to spirits in ancient Greek mythology that lie somewhere between mortals and gods. Later researchers, however, interpreted it as the classic demon with horns and a forked tail.

Second, we note that Maxwell refers to a “hole” in the Second Law of thermodynamics (and he charmingly writes the word in shorthand using theta and delta

). His goal in introducing the demon was to demonstrate, as we have said, that the Second Law is not an absolute law but one that depends on statistics. He also essentially ruled out the possibility of achieving any significant violation of it, because we are “not clever enough.”

However, this small hole in thermodynamics has potentially huge implications for physics and the world if it can be exploited, as we next discuss.

IV. Perpetual motion of the second kind.

Let us suppose we start with a box of gas, divided into two parts with Maxwell’s demon in control, at room temperature. We then use Maxwell’s demon to produce a temperature difference between the two box halves, with a negligible amount of effort (work) being done. Now, because there is a temperature difference between the two halves of the box, there is a pressure gradient. If the wall is movable, the higher temperature side of the box can do work and push the wall to compress the lower temperature side of the box, presumably until they reach an equilibrium. Overall, we might expect that the box ends up colder than the outside temperature, because it has converted some of its heat energy into mechanical work. But then we could thermally expose it to the outside air, letting it warm back up to room temperature. Then we apply Maxwell’s demon in reverse, and let a new temperature gradient push the wall back in the other direction. Then we let it reach room temperature again, and repeat.

The result is a machine that automatically turns the thermal energy of the air into work. That work energy will eventually become heat energy again, and will rejoin the room temperature thermal equilibrium of the atmosphere. Then we can do it again, and again. Essentially, the existence of Maxwell’s demon allows — in principle — for us to keep recycling the same energy over and over again to keep doing mechanical work. This applies both to the temperature demon and the pressure demon.

This sort of machine is often referred to as a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, one that takes advantage of Second Law violations. A perpetual motion machine of the first kind is one that violates conservation of energy, i.e. the First Law. Because the First Law is absolute and cannot be broken, first kind perpetual motion is impossible. But because the Second Law is evidently statistical in nature, our existing knowledge of it suggests that it is in principle possible to make a second kind perpetual motion machine.

I will stress again that there is no known way to perform such Second Law violations in practice, and no evidence that it ever happens. The Second Law is our explanation of why the universe seems to run down and always progress more towards disorder and away from order. A coffee cup knocked off of a table will fall to the ground and break, but we will never see a broken coffee cup spontaneously reform and launch itself back up onto the tabletop. None of the other laws of physics say that the latter event is impossible — they are all consistent with essentially running time backwards — but the Second Law indicates that it is impossibly unlikely that all the forces and energy of all the related parts of the system would come together in agreement in such a way that our coffee cup would be restored. The Second Law so informs our understanding of the universe that it is often considered the most fundamental of laws, as Eddington3 once remarked:

The law that entropy always increases—the second law of thermodynamics—holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations—then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation, well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.

Second Law perpetual motion machines, if they were possible, would utterly transform society. They would amount to free and clean energy for the entire world. This goes against everything we understand about how the universe works, which is why many physicists have spent a lot of effort trying to show that Maxwell’s demon doesn’t violate the Second Law at all or, to put it another way, that the Second Law is in fact more than statistical but an absolute law of nature.

You might ask why physicists are being so negative in trying to show that Maxwell’s demon can’t give us free energy, rather than trying to show that it can! I can think of two reasons. First: trying to prove the negative means you’re constantly looking for flaws in the argument, which psychologically you might overlook if you’re just trying to prove it works. Second: there’s an unstated physical principle that almost every physical effect that you can imagine in the lab has its analogue in the natural world. For example: natural nuclear reactors exist, as do what might be referred to as natural lasers! If Second Law violations were possible, we probably should have stumbled across an example already, either in natural physical phenomena or taken advantage of by evolution. The safest bet, and likely the correct one, as we will see, is that the Maxwell’s demon argument has a flaw.

V. Retiring Maxwell’s demon.

One big challenge in investigating Maxwell’s demon is that it is a poorly defined quantity. What sort of creature is it, how does it measure the incoming particles to decide whether to let them pass or not, how does it operate its door, and how does the door work itself? To be fair to Maxwell, I don’t think he ever intended for this to be more than a clever argument to elucidate the Second Law, but in order to seriously analyze it, we need a quantitative model.

(My discussion here draws from a nice 2009 review4 by Maruyama et al. and a historical survey by Rex5, though any errors in the technical details are my own. In this section, I’m really pushing the limits of my own limited understanding.)

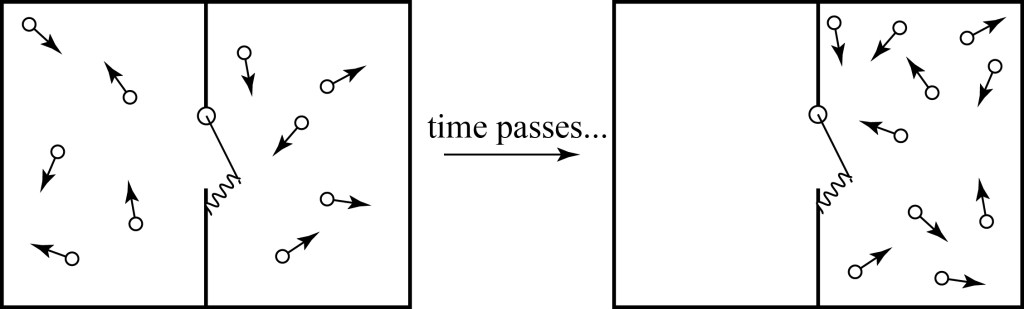

One approach to defining the demon is to make a purely mechanical device that emulates the behavior of the pressure demon; this is the approach introduced by von Smoluchowski in 19126. We imagine a spring-loaded door on the wall dividing our gas, which can only open in one direction, as illustrated below. Then molecules hitting it from the left can knock it open and come through, while those coming from the right just bounce right off. The idea is that, given enough time, there will be significantly more molecules on the right then on the left; it will have created a pressure difference.

This does not in fact work, and it is relatively easy to explain why! In order for particles to be able to pass from the left to the right, the spring on the door has to be relatively weak — weak enough to easily allow particles to bash through. But when particles bash through, they are likely transferring some energy to the door. The door becomes thermalized, and after it accumulates enough energy, it will randomly flutter open and shut, like a loose screen door on a house during a thunderstorm. When this happens, particles will be free to flow back to the left again. Even though we are perhaps able to slightly increase the particle numbers on the right for a short period of time, eventually we will find that the equilibrium condition returns. The result will be very similar to the natural random fluctuation of particle positions that we have discussed previously.

One can try to de-thermalize the door by cooling it in order to keep the demon functioning, but if your cooling process is any sort of normal refrigeration process, then entropy will increase during the cooling, and calculations can show that the overall entropy of the combined box/refrigeration system will increase — the Second Law will be satisfied.

Let us next imagine an actual intelligent demon and see what sort of limitations it might face. Researchers like Leon Brillouin7 looked at the implicit assumption that the demon can observe the incoming particles, i.e. perform measurements on the particles, for free. He imagined that the particles are observed and measured optically, i.e. by imaging them with light, and found that entropy is created in the measurement process. This entropy increase is more than enough to counterbalance the decrease in entropy caused by the demon itself.

How does measurement by light cause an increase in entropy? Light particles themselves — photons — have entropy, and when they scatter randomly off of particles of the gas, their own organization becomes more disordered, increasing entropy. So optical measurement of particle positions automatically breaks Maxwell’s demon, and the Second Law stays secure.

But it is in principle possible to measure the particle behavior without photons, and here we end with the most subtle argument yet. Researchers gradually became aware of an intimate connection between entropy and the mathematical theory of information, and that one must consider the information gathered about a thermodynamic system as part of the system itself. In particular, in 1982 Bennett8 argued that the measurement process itself does not necessarily involve an increase in entropy, but that the information must be stored after the measurement process and when that information is inevitably erased, that erasure of information results in an entropy increase that balances out the reduction of entropy of the gas in a box system. This feels similar to the spring-loaded door of von Smoluchowski: one might be able to temporarily produce a limited reduction of entropy, but it will inevitably be overwhelmed by an increase.

I have some idea of how I might describe how all this works in detail, but I think I will save that for a separate blog post and make sure I learn a bit more before trying to explain it!

So, in the end, the current consensus on Maxwell’s demon is that it cannot be used to cause any significant violation of the Second Law, and cannot be used to make perpetual motion machines. We can say that the Second Law isn’t just a statistical law, but apparently has a more strict fundamental foundation to it. Researchers nevertheless continue to investigate Maxwell’s demon and its connection to the Second Law, because it is a surprisingly fruitful way to increase our understanding of how our universe works, even if we can’t break any laws.

VI. 1879: People get angry at the demon.

So, finally, with all this background, let me come back to the article9 in The Popular Science Monthly, titled “Explanations that do not explain”! I almost feel like whoever wrote the article was in a particularly bad mood that week, because the whole thing is incredibly cranky! It begins:

THERE is a certain class of minds whose efforts to explain things generally leave them more obscure than they were before. In undertaking to represent a. question they complicate rather than simplify it, and instead of helping the learner to understand a subject they hinder him. This failure to make things lucid and comprehensible is due to various causes. Oftenest, it comes from a total neglect of the art of luminous writing, and it is unfortunate that many scientific men are not a little perverse about cultivating this art. They do not, as a matter of conscience, make any effort to enter into the state of mind of the parties addressed, and their expositions, therefore, often fail from lack of adaptation. Sometimes a subject familiar to teachers of great capacity is still too abstruse to be grasped by common minds. Sometimes the expounder does not understand the subject himself ; and not unfrequently hypotheses are invented to explain unexplainable things, and which serve only to increase existing difficulties. A marked illustration of this is afforded by a lecture delivered not long ago before the Royal Institution, by the eminent physicist and mathematician, Sir William Thomson, who announced as his topic of discourse the curious subject, ” Maxwell’s Sorting Demons.”

Basically, the writer is saying that Thomson’s lecture on Maxwell’s demon makes the subject of thermodynamics more confusing! I am almost impressed by their willingness to trash not only Thomson but Maxwell as well, two of the recognized great minds in physics, even at the time.

The lecture was mainly devoted to an explication of the phenomena of the diffusion of liquids and the principles it involves. Professor Thomson had many tubes prepared, each containing two liquids of different colors, to represent the progress of diffusion, while some ingenious experiments were made by throwing the spectra of various solutions upon the screen with an electric light. The diffusibility of solids and gases was also referred to, and a just tribute paid to the memory of Graham, whose name stands most prominently associated with this branch of research.

So Thomson was really spending much time talking about how gases diffuse, which we spent a good amount of time talking about in the context of entropy.

Sir William Thomson’s reasons, how ever, for bringing forward these phenomena of diffusion were that they stand very closely related to the present theories and speculations concerning the molecules of matter, and which aim to account for their motions. In diffusion, the molecules gradually intermingle, according to definite laws, which are variable in different cases. The molecules do not move capriciously or irregularly, as all chemical action and all crystallization prove. But why do they move this way or that, and why always go the same way in the same conditions ? This “why” is the perplexing word of science, and when we get down among objects the very existence of which is hypothetical it carries us far beyond our depth. But Professor Maxwell thinks he gives us aid here by inventing a host of little demons—living creatures with wills and infallible intelligence—which sort the molecules and regulate their extraordinary motions. In a very brief abstract of his lecture which Sir William Thomson has published, he thus explains the attributes and offices of these remarkable agents:

Here we can see that the author is very annoyed by, and doesn’t see, the point of Maxwell’s thought experiment. We then get part of Thomson’s own written description, which is quite lovely:

Clerk Maxwell’s ” demon ” is a creature of imagination having certain perfectly well defined powers of action, purely mechanical in their character, invented to help us to understand the ” dissipation of energy ” in nature. Ho is a being with no preternatural qualities, and differs from real living animals only in extreme smallness and agility. He can at pleasure stop, or strike, or push, or pull any single atom of matter, and so moderate its natural course of motion. Endowed ideally with arms and hands and fingers—two hands and ten fingers suffice—he can do as much for atoms as a piano-forte player can do for the keys of the piano—just a little more, ho can push or pull each atom

in any direction.

He can not create or annul energy ; but, just as a living animal does, he con store up limited quantities of energy, and reproduce them at will. By operating selectively on individual atoms he can reverse the natural dissipation of energy, can cause one half of a closed jar of air, or of a bar of iron, to be come glowingly hot and the other ice cold; can direct the energy of the moving molecules of a basin of water to throw the water up to a height and leave it there proportionately cooled (1° Fahr. for seven hundred and seventy-two feet of ascent) ; con ” sort “the molecules in a solution of salt or in a mixture of two gases, so as to reverse the natural process of diffusion, and produce concentration of the solution in one portion of the water, leaving pure water in the remainder of the space occupied ; or. in the other case, separate the gases into different parts of the containing vessel.

The classification, according to which the ideal demon is to sort them, may be according to the essential character of the atom : for instance, all atoms of hydrogen to be let go to the left, or stopped from crossing to the right, across an ideal boundary ; or it may be according to the velocity each atom chances to have when it approaches the boundary : if greater than a certain stated amount, it is to go the right; if less, to the left. This latter rule of assortment, carried into execution by the demon, disequalizes temperature, and undoes the natural diffusion of heat ; the former undoes the natural diffusion of matter.

This is, to me, a quite charming description of Maxwell’s demon! What it is missing, however, and what is key, is why this demon is being considered in the first place: an illustration of the statistical nature of the Second Law. Without this argument, Maxwell’s demon sounds like a strange pointless fantasy, which may have been the goal of the author of the editorial.

The author concludes:

This looks to us like a somewhat ridiculous way of evading the real difficulties in the explanation of molecular motions and their effects. All nature is supposed to he filled with infinite swarms of absurd little microscopic imps, which are so omniscient that they direct the invisible and insensible movements by which the whole order of nature is determined and maintained. When men like Maxwell, of Cambridge, and Thomson, of Glasgow, lend their sanction to such a crude hypothetical fancy as that of little devils knocking and kicking the atoms this way and that, in order to explain the observed changes of natural phenomena, we may well ask, What next ? This is a palpable case of contriving an artifice to explain a subject which yet leaves the subject more obscure than ever. There were difficulties enough with the molecules considered alone, but when complicated with another hypothetical order of beings the difficulties are redoubled, for we have now to explain the explanation. There is a great proneness to invent explanations which only remove the trouble one step further away. Sir William Thomson’s hypothesis of the origin of terrestrial life by means of germs, brought to our planet from some unknown source by meteorites, is another example of explanations by assumptions, in which nothing is explained. There is a class of scientific men who feel it incumbent upon them to answer all questions. They do not seem to appreciate the fact that there are limits to our knowing, which had bettor be honestly acknowledged, instead of offering conjectures which are mere travesties of legitimate theory, and absurdities in science.

I find this angry screed quite amusing, because it is clear that the author has completely missed the point! Like all good thought experiments, Maxwell’s demon actually simplifies the issues by breaking it down to a very simple and understandable, albeit unrealistic, scenario.

This is a good reminder that even the most brilliant scientific ideas end up having their detractors!

With this, I will wrap up this extremely long blog post. I hope you’ve learned a bit about thermodynamics and its foundations through the action of Maxwell’s demon, and aren’t left with an impression like the editors of The Popular Science Monthly.

*********************************************

- Cargill Gilston Knott (1911). “Quote from undated letter from Maxwell to Tait”. Life and Scientific Work of Peter Guthrie Tait. Cambridge University Press. pp. 213–215.

- W. Thomson, Kinetic Theory of the Dissipation of Energy . Nature 9, 441–444 (1874).

- A. Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World; J.M. Dent & Sons: London, UK, 1935; p. 81.

- K. Maruyama, F. Nori, and V. Vedral, Colloquium: The physics of Maxwell’s demon and information,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 81 (2009), 1.

- A. Rex, “Maxwell’s Demon: A historical review,” Entropy 19 (2017), 240.

- M. von Smoluchowski, “Experimentell nachweisbare, der Ublichen Thermodynamik widersprechende Molekularphenomene,” Phys. Zeitshur. 13 (1912), 1069.

- L. Brillouin, “Maxwell’s Demon Cannot Operate: Information and Entropy. I,” J. Appl. Phys. 22 (1951), 334.

- Bennett, C.H. The thermodynamics of computation—a review. Int J Theor Phys 21, 905–940 (1982).

- “Explanations that do not explain,” The Popular Science Monthly 15 (1879), 410.

Interesting reference in there, #4 (K. Maruyama, et al…) Includes some thought experiments (with some experimental support) suggesting that gravity plays a role in thermodynamic direction, and extending into some sci-fi worthy implications for a Shannon entropy driven or enhanced heat engine that essentially extracts energy from information loss.

>All nature is supposed to he filled with infinite swarms of absurd little microscopic imps, which are so omniscient that they direct the invisible and insensible movements by which the whole order of nature is determined and maintained.

It appears from this paragraph that the author of about the editorial was under the impression that Maxwell and Kelvin (Thomson) proposed Maxwell’s daemons as an explanation for the Second Law, hence the complaint that it’s unsatisfactory as an explanation. (And indeed it would be, for that.) Even while correctly summarizing Kelvin’s description of the daemon’s operation as reversing the effects of the Second Law, they seem to have missed that the daemons are doing something that in fact is not observed, and that nobody was proposing that the world is full of such daemons. (In contrast, Kelvin really did propose panspermia, which I agree fails to explain the origin of life.)

OK, it’s been a while since I busted in on your comment section, but just speaking on behalf of the demonic population, opening and closing a door for molecules requires effort. It doesn’t happen on its own. It’s work. It’s gonna require my energy and my time (not to mention a lot of union paperwork) to get me to move that door. It’s not like that door doesn’t weight something—it’s strong enough to block a moving molecule! And it’s not like that hinge is magically frictionless either. Every time I slam or open that door, I’m putting time and energy into this little box, so don’t you try to wiggle out of our contract by pretending you got yourself some magically closed thermodynamic system. You want magic? You get yourself a pixie, not a demon. Magic pixie dust can do just about anything. Happy 18th blogiversary, BTW.