This is part 7 in a lengthy series of posts attempting to explain the idea of quantum entanglement to a non-physics audience. Part 1 can be read here, Part 2 can be read here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, Part 5 here, and Part 6 here.

It was hard to avoid the feeling that somebody, somewhere, was missing the point. I couldn’t even be sure it wasn’t me.

— Douglas Adams, Last Chance to See (1990)

Quantum physics really began with Einstein’s 1905 introduction of the idea of photons — particles of light — to explain the photoelectric effect, and the mathematical theory was developed in earnest over the next 25 years. It has been an incredibly successful theory, and not only predicts all sorts of mind-boggling phenomena like quantum entanglement, but has had these phenomena experimentally verified over and over again.

However, we are now almost 120 years past the formal introduction of quantum physics, and still do not have a certain answer to the question: what does it all mean? Anyone who studies quantum physics probably feels at some point like Douglas Adams did in the quote above (though he was talking about something completely different).

Throughout this series of posts, we have used what is usually called the “Copenhagen interpretation” of quantum physics to interpret the quantitative theory:

All the properties of a quantum particle remain in an undetermined state, evolving as a wave, until they are measured. Upon measurement, the part of the wave associated with the measurement collapses into a definite state, the height of the wave being a measure of how likely it is to be found in that state.

This interpretation was first conceived by Niels Bohr and his assistant Werner Heisenberg over the years 1925-1927, while they pondered the known information about the quantum world at Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen. This interpretation is still taught to physics students, and for good reason: it is a (relatively) easy way to interpret the strange tangle of quantum physics, and every quantum experiment we can do can be readily explained through this interpretation.

The problem is that the Copenhagen interpretation is clearly an incomplete description. Two really big interconnected issues stand out in the quoted description above: What is a measurement, and who does the measurement? What is a quantum state collapse?

Let’s start with the second question. We now know that all matter can be described by the quantum theory, and in principle their evolution can be described by the wave equation introduced by Schrödinger in 1925. This includes the interactions of multiple particles — when they interact, their waves become “entangled,” but nothing in Schrödinger’s equation introduces a “collapse” of the quantum state to a definite state. In fact, quantum state collapse is rather crudely tacked on to the existing theory; we say that all quantum particles evolve together as a wave until they are “measured,” at which point the state “collapses.”

But what is a “measurement?” For early researchers in quantum physics, “measurement” referred simply to experimental measurements made in the laboratory by physicists. A “measurement device” was any device that was big enough to be treated by the laws of classical physics, and as a rule of thumb it was said that quantum particles would evolve as a wave until a measurement device causes a “quantum collapse.” You can see the somewhat circular logic here: “What causes a quantum collapse? A measurement. What is a measurement? Whatever causes a quantum collapse.”

But since all matter can be described by quantum physics, this means that both the experimental apparatus used to measure quantum effects and the researcher using the apparatus are also quantum objects. There is no obvious reason why, according to the existing theory, we should expect a device or a person to collapse a wavefunction. This is exactly the issue that Schrödinger was getting at with his “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment, as pictured below.

A living cat is put into a box with a radioactive source, and a radiation detector will release poison gas if a radioactive decay is detected. If the setup is designed so that there is a 50% chance that a radioactive decay occurs in a certain time, then at that time the Copenhagen interpretation of physics suggests that the cat and the radioactive source will be entangled, with a quantum state of the form

Thus, until the box is opened, the cat is in a wave superposition of being “living” and “dead,” which seems paradoxical and, more importantly, directly in conflict with our experience.

This can be resolved by saying that the cat is the one who makes the measurement and causes the state collapse. But what makes the cat special? There is no distinction between “living” and “dead” in quantum physics, so there is no reason to think that the cat causes the quantum collapse any more than the radiation detector or the experimenter outside the box.

These unanswered questions about measurement and state collapse in the Copenhagen interpretation have led scientists and philosophers to seek alternative interpretations of quantum theory. In this post, now that my lengthy introduction is done, we attempt to summarize some of the main alternatives, of which there are many!

A few caveats before we begin! First, I am definitely not an expert in this sort of quantum philosophy, so my descriptions of the different interpretations may not be perfect. I will not be able to answer particularly deep questions about these concepts, because I have not spent as much time on them as the experts. “Caveat emptor,” as they say.

Second, we should note that this discussion of quantum interpretations is largely a philosophical, not a physical, discussion. We have noted that all existing experimental observations can be explained using the Copenhagen interpretation; if one is only concerned with being able to predict experimental outcomes from the theory, then Copenhagen is good enough — at least as far as we’ve found! This, in fact, is why physicists often use the tongue-in-cheek saying “shut up and calculate” when talking about quantum physics. In short: “it works, so don’t ask any questions.” The interpretations we will discuss here are attempts to fix the logic of quantum physics, and most of the interpretations do not — as yet — provide any experimental differences from Copenhagen. But as the previous discussion of Bell’s inequalities shows, questions that seem purely philosophical can unexpectedly turn out to be very experimental, so the philosophical exercise is a potentially useful one.

Finally, let me note that each of these interpretations raises as many questions as it answers! This is not a bad thing — interesting science should lead to insights that unveil new things to ask about. My PhD advisor used to say of one of his students, “he creates as many problems as he solves!” This was in fact an ironic compliment: creating new interesting problems to study is one of the most important things a scientist can do.

So without further ado, since we’ve had enough ado already, let’s look at a variety of quantum interpretations, going from what I consider the most mundane to the most exotic!

Spontaneous collapse. One suggestion is that the wavefunction spontaneously and randomly collapses on its own over a long time scale. Such an approach essentially solves the measurement problem by detaching the quantum wave collapse from measurement entirely.

In such an approach, researchers postulate that Schrödinger’s wave equation is incomplete, and that there should be an extra term that induces these random collapses. The earliest theory of this form is known as GRW theory, as it was introduced in 1986 by Ghirardi, Rimini and Weber1, but there have been many other variations2.

How does spontaneous collapse solve the measurement-collapse problem, and in particular how does it resolve the issue that big objects act classically and small objects act quantum-like? The theories are constructed such that the collapse of one particle’s wavefunction induces any particles strongly interacting with it to also experience wavefunction collapse. You could imagine it like a set of dominos being toppled — the first domino falling causes all the other dominos to fall in turn.

The characteristic time over which a wavefunction typically collapses is assumes to be about 1016 seconds in GRW theory, or roughly 300 million years! For an individual particle in an experiment, one would never expect to see a quantum collapse. For a large number of atoms, however, collapse would happen very quickly. For example, if we had a one centimeter cube of copper, containing some 1024 atoms, we would expect quantum collapse to happen roughly every 1016/1024 = 10 nanoseconds, and we would not see the wave effects of our cube in any ordinary measurement.

Spontaneous collapse theory stands out from the others in that it is, in principle, experimentally testable. The collapse of the wavefunction of a system of particles will change the evolution of the particles, and this could in principle be measured if we had a system of particles larger than a single atom but presumably smaller than our cube of copper. In fact, experimental tests have been done, but as far as I know they have not produced any conclusive results (as we would have heard about it).

One limitation of spontaneous collapse theory is that there are many possible ways to modify Schrödinger’s wave equation to create a collapse model, and we have no way of determining which one is correct. When Schrödinger developed his equation, he was able to rely on physical and mathematical intuition to determine the answer, but we have no such intuition for spontaneous collapse.

In spontaneous collapse models, Schrödinger’s cat would be always be in a deterministic state, because its wavefunction would be constantly collapsing. It would either be alive or dead, depending on whether the radioactive decay has happened.

Pilot wave. The oldest alternative to the Copenhagen interpretation is known as the pilot wave theory, and the earliest form was introduced by de Broglie, the brilliant researcher who first postulated that matter has wavelike properties. His attempt at a pilot wave theory was quickly shown to be flawed, however, and it was abandoned, but in the 1950s David Bohm introduced a revised version3 that overcame the earlier objections, and pilot wave theory is often called “Bohmian mechanics.”

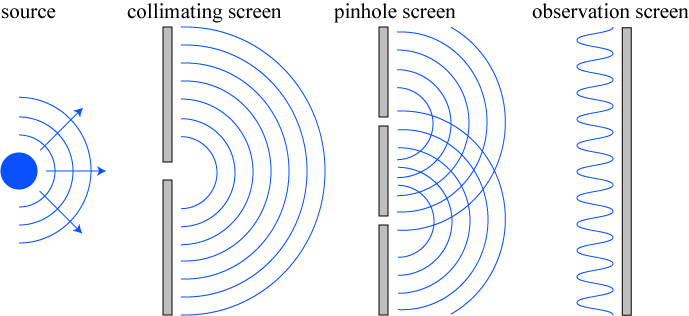

In pilot wave theory, it is assumed that both the wave and the particle are real entities, and the point-like particle is guided through a physical system like a surfer catching a gnarly wave. Pilot wave theory essentially removes the need for wavefunction collapse: the particle always exists at a definite location, but it is most strongly guided to the locations where the wave has the highest intensity, which reproduces the probabilistic appearance of quantum physics. In a system like Young’s interference experiment, the wave goes through both pinholes and produces an interference pattern on the detector screen, but the particle definitely goes through one hole or another.

Because the particle always exists at a definite location, Bohmian mechanics is in fact a “hidden variable” theory. But doesn’t this contradict the previous post in this series, where we said that John Bell disproved hidden variables? Not quite — Bell’s theorem, and the experiments that followed, showed that observed quantum physics cannot be modeled by a local hidden variable theory, but Bohm’s pilot waves are nonlocal. “Locality” is the assumption that two or more particles are not linked over a long distance, but Bohm’s theorem suggests that the wave of one or more particles can cause effects over such distances. We have noted previously that nonlocality is itself a very strange concept to accept, so whether one finds Bohm’s hidden variable theory acceptable or not is a matter of taste.

Bohm has shown that his modified wave-particle mechanics reproduces known quantum theory. However, the math is extremely complicated and difficult to apply to systems of more than one or two particles. Furthermore, as far as I know there are no known experimental tests of Bohmian mechanics, so it remains for the moment more of a philosophical argument than a physical one.

In Bohm’s theory, Schrödinger’s cat would always be either alive or dead, for even though the wave of the cat may have a superposition state, the particles of the cat would be in a definite alive or dead arrangement.

Many worlds. The most famous alternative interpretation of quantum physics is often referred to as the “many worlds” interpretation. It was first introduced4 by Hugh Everett III in 1957, and has gained a lot of serious supporters in the theoretical physics community.

Many people have probably heard of this theory in reference to a “multiverse” or “infinite parallel universes,” but Everett’s original formulation is much more modest. We have seen that we can describe a single (unmeasured) quantum quarter by a wavefunction something like as follows:

If we entangle two quarters together, we get a wavefunction something like:

What is important to realize is that we still have a single wavefunction when we describe two quarters, albeit a more complicated one. If we add a third quarter, we will have a single wavefunction that describes all three, and so on. Everett takes this to the logical conclusion that there is a single wavefunction that describes the entire universe. This single wavefunction evolves in time and all possible outcomes of any quantum event all appear in this wavefunction. This “universal wavefunction” removes the need for quantum collapse, as every “measurement” is just following a particular possibility in the quantum state.

The more I ponder “many worlds,” the more reasonable it seems to be, though I still don’t fully ascribe to it. One sticking point I had for a long time was wondering if “many worlds” in fact does solve the measurement problem: why do we, in our lives, only experience one reality, if the wavefunction has an uncountably infinite number of branches? My thinking: since our brains are part of the wavefunction, and our consciousness is built into our brains, our perception of reality is based on whatever everything else around us is doing. Every branch of the “universal wavefunction” has a unique state of our consciousness, so each branch is experiencing something different, and unique. In short: since our perceptions and our brain state are based on what everything else around us is doing, we only experience the one state of the branch we are currently on. (Other branches, or other states of you, are experiencing things differently.)

It’s a lot to take in, and I wouldn’t bet a lot of money on “many worlds” being the true interpretation of quantum physics, especially since there is no known way to confirm it experimentally. At the very least, it serves as a good example to show that it is possible to imagine ways that quantum theory can work that don’t suffer from the measurement and collapse problems.

It is worth noting that statements that refer to “infinite parallel universes” in the many worlds interpretation are misleading, because there is still just a single universe, with a single wavefunction — it just so happens that the universe is a quantum state, not a classical one.

In a many worlds theory, Schrödinger’s cat would be alive in some branches of the wavefunction, and dead in others. In any particular branch, however, it would be in a definite state.

Relational quantum physics. Let me mention one more approach, which I have only read about recently in the book Helgoland by Carlo Rovelli. (I understand this one the least, but let me give it a try anyway.)

Relational quantum physics keeps the wavefunction collapse and measurement process, but makes them relative to the particular observer. To put it another way, it solves the question of “who makes the measurement?” by saying that everyone/everything is an “observer” who makes “measurements.” The difference is that different observers will predict different things based on the amount of interaction they have with a system.

This is difficult to explain, so let’s use Schrödinger’s cat as an example. From the cat’s perspective, it is either alive or dead, because it either sees the poison released or it doesn’t. But the scientist outside the box cannot know whether the cat is alive or dead, so he “sees” the quantum wave — that is, he could measure the quantum interference of the cat in an experiment. When he opens the box, though, his perception will agree with the cat’s — they are now both in the same “frame of reference.”

My take on this is that relational quantum physics is in a sense a generalization of traditional Einstein relativity. In Einstein’s special relativity, observers moving at different velocities will disagree on whether two events are simultaneous or not — this is called “relativity of simultaneity.” Relational quantum physics argues that all of our perceptions of reality are in a sense relative. The cat in the box has more information than the scientist outside the box, so the two will have quantifiably different perspectives on reality until the box is opened and they have the same information.

There is actually some precedent for this in quantum physics. It is well-known that wave interference depends on the amount of information one has about a system. In Young’s experiment, illustrated below, one only sees interference fringes on the observation screen if one cannot tell which hole the particle has gone through. Any means by which one attempts to measure which pinhole the light particles go through will cause the interference to vanish. We usually say that interference is related directly to the indistinguishability of the light’s path. And this is a general principle that applies across all quantum experiments.

My understanding, in the relational model, is that every photon, from its own perspective (if a photon could have a perspective) sees itself go through a single pinhole and land on the observation screen. From the experimenter’s point of view, however, he cannot tell which path the photon has gone through, and that ignorance manifests in a wave pattern. However, each individual photon still lands at a definite point on the screen; it is only through measuring many photons that the wave effects become evident.

Relational quantum physics is, according to Rovelli, a philosophy that says that only the interactions between different objects are important, and the “reality” of an object by itself is not determined. When Werner Heisenberg first introduced a quantum theory, before Schrödinger, he formulated it as a set of relations between interacting objects. Relational quantum physics is an intriguing attempt to remove the issues of quantum physics by returning to this perspective.

Conclusions? So, in the end, we can say that there are many different ways that people have attempted to resolve the problems with the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics, but none of them have been conclusively proven experimentally, and most of them we have no idea how to test them at the moment! There are even more interpretations out there, and there are probably more plausible explanations that have not been conceived of yet. Someone may come up with a surprising way to experimentally answer the question one day, but it may turn out that the answer is something completely unexpected… just like quantum physics itself was.

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy

(Hamlet, 1.5. 165–66)

**********************************

- Ghirardi, Rimini and Weber, “Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems,” Phys. Rev. D 34 (1986), 470.

- Bassi et al, “Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 85 (2013), 471.

- Bohm, “A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of “Hidden” Variables. I,” Phys. Rev. 85 (1952), 166.

- Everett, “‘Relative state’ formulation of quantum mechanics,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 29 (1957), 454.

The relational model makes by far the most sense to me.