My training and background as a physicist is largely in the field of so-called classical optics: the study of the wave properties of light. Lately, however, I’ve been planning more investigations into quantum optics — the study of the quantum particle properties of light — which has recently culminated in my first published paper in the field.

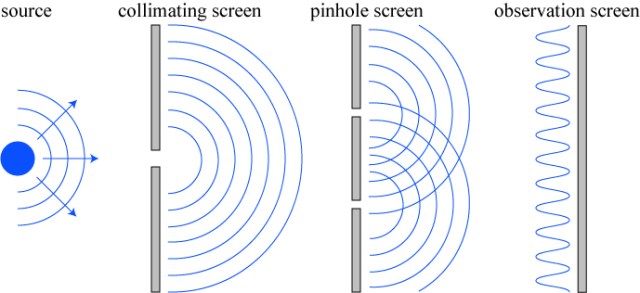

One topic I’ve been reviewing in quantum optics is the concept of a “quantum eraser.” The idea arises from the general observation that wave interference is directly connected with a lack of knowledge about the evolution of a quantum particle. The classic example of this is Young’s interference experiment, illustrated below.

A source of light is collimated by a small hole in one screen, and then the light simultaneously illuminates two pinholes in a second screen. Light coming from those two holes propagate to an observation screen, where the waves from the two pinholes interfere with each other and produce bright and dark fringes that look something like this:

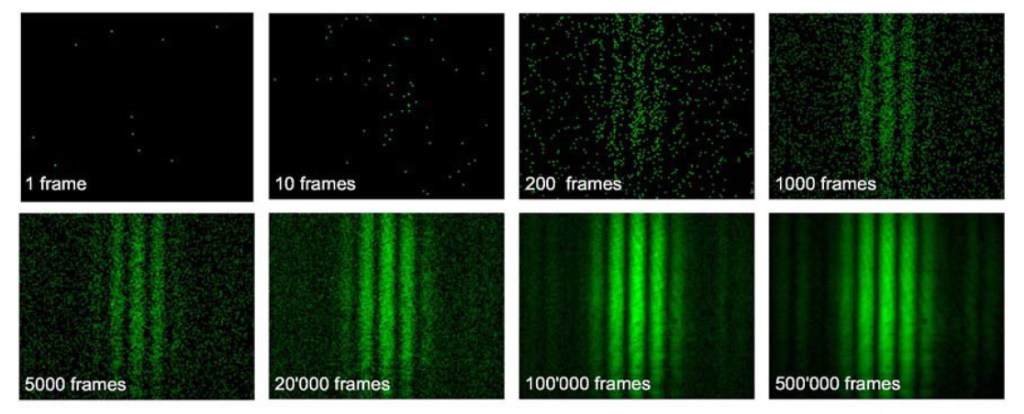

This argument stretches down to the single photon level. In that case, if we send a single photon through Young’s experiment, the probability of seeing the photon arrive at a point on the observation screen is proportional to the interference pattern. That is: the photon is more likely to arrive at some points rather than others due to the wave interference properties of the photon. If we tabulate the positions of a lot of photons over time, we find that the classical wave interference pattern emerges:

Here is where the idea of “information,” loosely defined, comes into play. The interference pattern for a single photon comes from the recognition that the photon wavefunction passes through both pinholes simultaneously — that is, we as experimental observers have no idea which pinhole the photon has gone through, so it has in a sense gone through both. But if we somehow set up an apparatus that can measure which pinhole the photon has gone through, we will find that the interference pattern disappears completely. Apparently, our knowledge of the path of the photon destroys the interference pattern or, conversely, our ignorance of the path of the photon allows the interference pattern to form.

The idea of a quantum eraser, first proposed by Marlan O. Scully and Kai Drühl in 19821, grows from this. Let us imagine we perform an experiment like Young’s experiment where we measure “which path” information — if nothing else is done, we expect that the interference fringes will not be present on the observation screen. Now suppose that we can somehow “destroy” this information after the photons have passed through the pinholes but before we actually measure the position of the photon on the observation screen. Because the information is no longer present, we expect to see the interference fringes manifest on the screen again! By “erasing” the information, we have caused the wave behavior to appear again. This is the basic concept of a quantum eraser.

However, this is another weird twist to all of this. It is furthermore possible in many cases to choose whether or not to destroy the “which path” information not only after the photon has passed through the two pinhole screen but even after the photon is measured at the observation screen! In this case, the phenomenon is referred to as a “delayed choice quantum eraser.” This bizarre result has often been describe as information “traveling backward in time,” as it superficially seems like the photon must revise its behavior in the past in order to give a consistent result — conforming to the presence or absence of interference — in the present. As we will see, however, this “time travel” interpretation of the is simply wrong, though the explanation of what is really going on is just as fascinating and subtle.

We’ll tackle the quantum eraser explanation in two parts, both of which will be based on Young’s interference experiment. In the first part, we will describe the basic principles using what I will call a trivial eraser, which doesn’t explicitly need quantum physics to explain it. Then we will dive into a full quantum eraser. Settle in for a somewhat lengthy post! It is also one of the most complicated things I’ve ever tried to explain in a blog post, so be patient with me!

For our discussion of the “trivial” eraser, we follow the discussion of a paper by Hillmer and Kwiat, “A Do-It-Yourself Quantum Eraser,” which appeared in 2007 in Scientific American2. This demonstration doesn’t quite cover the full quantum weirdness of the quantum eraser, but it is co-written by Paul Kwiat, who is one of the biggest quantum optics names out there, so we consider that a fair endorsement!

Up to this point, we have left unanswered one of the key questions related to a quantum eraser: how does one measure the “which path” information of a photon? In the trivial case, we can use the polarization of the photon.

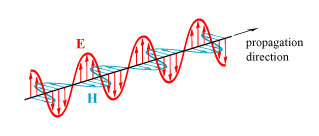

Light is what is known as a transverse electromagnetic wave, which means that it consists of oscillating electric fields (E) and magnetic fields (H) that oscillate perpendicular (transverse) to the direction the wave is going.

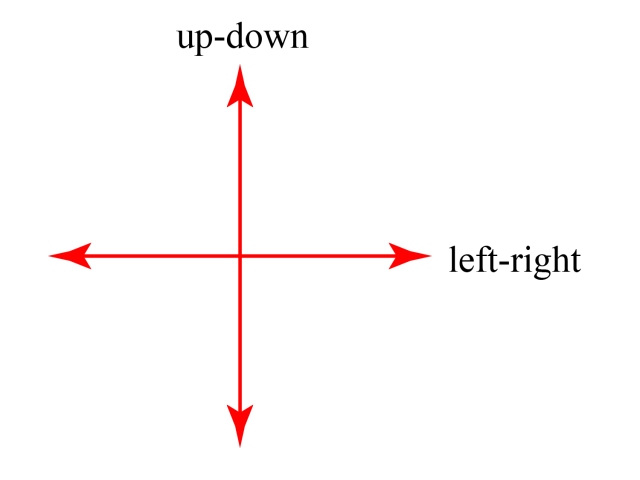

The term “polarization” is of historical origin and refers to the behavior of the electric field. Because the wave is transverse, there are always two distinct ways for the electric field to oscillate for any direction of travel. For example, we can say that the two choices are ‘up-down’ (vertically) and ‘left-right’ (horizontally). As seen when looking head on at the beam of light, these choices would look like:

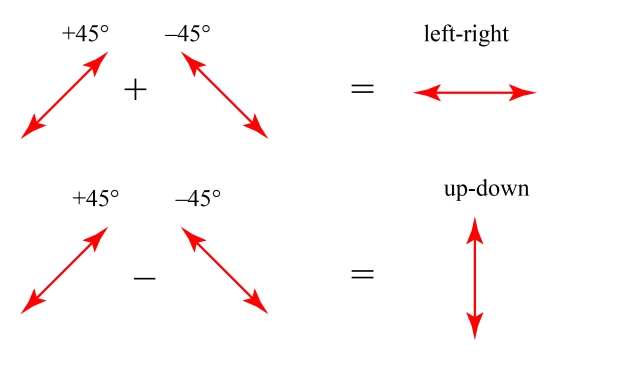

It will be relevant for the discussion going forward to note that any polarization state can be written in terms of any pair of distinct states. For example, polarization at +45 degrees and -45 degrees can be written as combinations of up-down and left-right:

This image also inadvertently shows an important aspect of light polarization: perpendicular polarization states don’t create interference. If we directly add an up-down wave and a left-right wave of equal amplitudes, they will never cancel each other out: they will just become a +45 degree wave.

We can reverse this, and describe up-down and left-right polarization in terms of the 45 degree states:

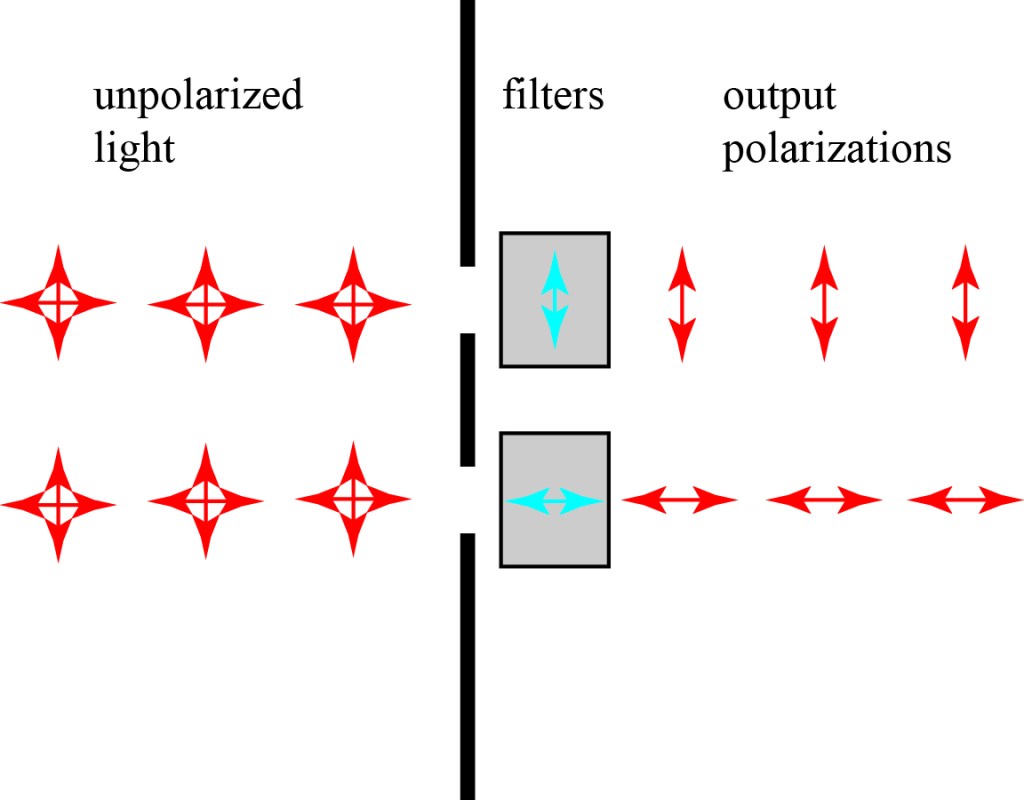

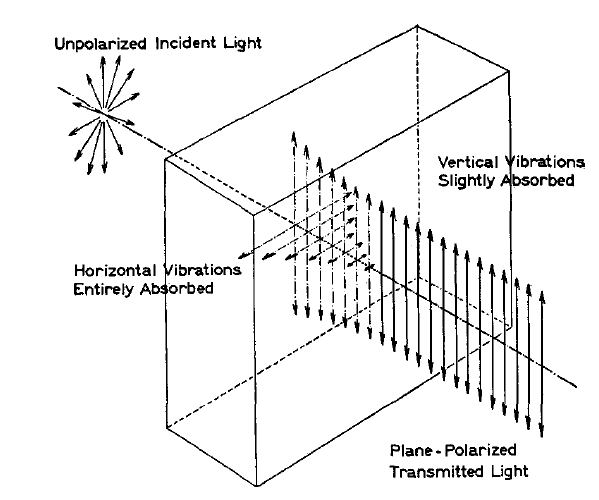

Now let’s briefly talk about how we measure polarization. The standard method is to use a polarizer, which is a device that allows light polarized along one direction to pass unimpeded while fully absorbing light along the perpendicular direction. I particular enjoy this image from a 1938 paper on polarizers.

This image shows unpolarized light — light that is a random mixture of horizontal and vertical — passing through a polarizer that absorbs horizontal polarization and allows vertical polarization to pass mostly without reduction.

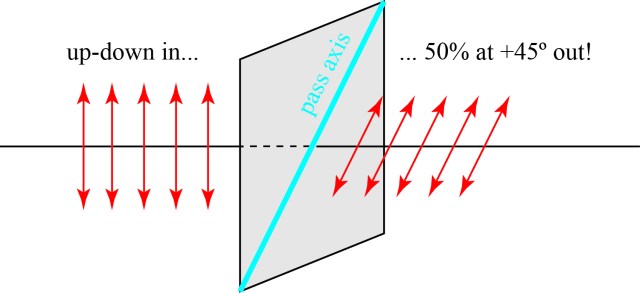

An important part of the interaction of polarized light with a polarizer comes from the previous two images combined. Suppose we send up-down light into a polarizer oriented at 45 degrees. We can say that up-down light is a 50-50 mix of light at +45 and -45, so 50% of the light passes through the polarizer, and what comes out is oriented at 45 degrees.

(Most of these images are coming from my recent post on quantum cryptography, which isn’t a coincidence — lots of fundamental quantum physics is studied with photons and polarization.)

So a polarizer not only blocks some of the light impinging on it, but changes the state of the light that makes it through. If we think about it at the single photon level, a single up-down photon has a 50% chance of passing through a +45-oriented polarizer. If it makes it through, the photon is now +45 polarized. Another way to think about it: a polarizer acts as a device that measures polarization and changes the state of polarization as a result.

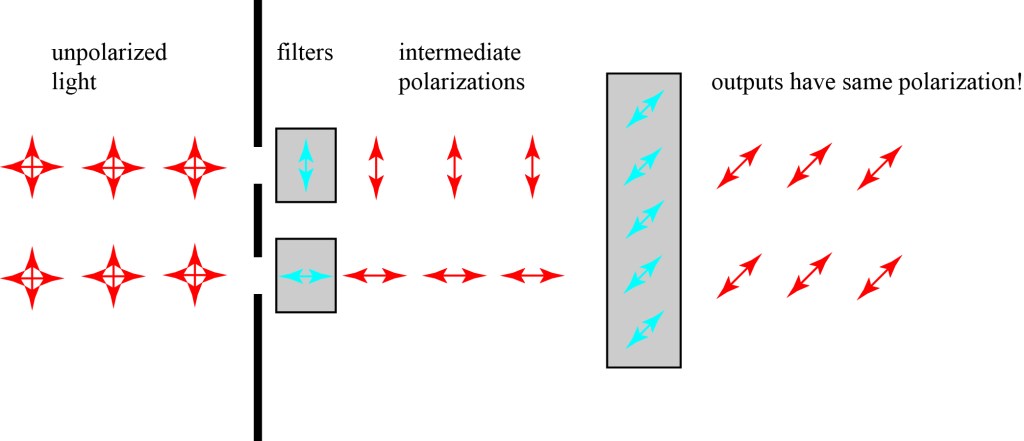

This brings us to the trivial quantum eraser. One way to create “which path” information is to place a polarizer in front of each of the pinholes in Young’s experiment, one horizontal, one vertical. This directly correlates the hole that light goes through with the polarization state of the light — because we can measure the polarization of light, we can determine which hole the light went through. In the picture below, I show the “head on” view of the polarization at each location for clarity (much harder to show what everything is doing using an isometric approach).

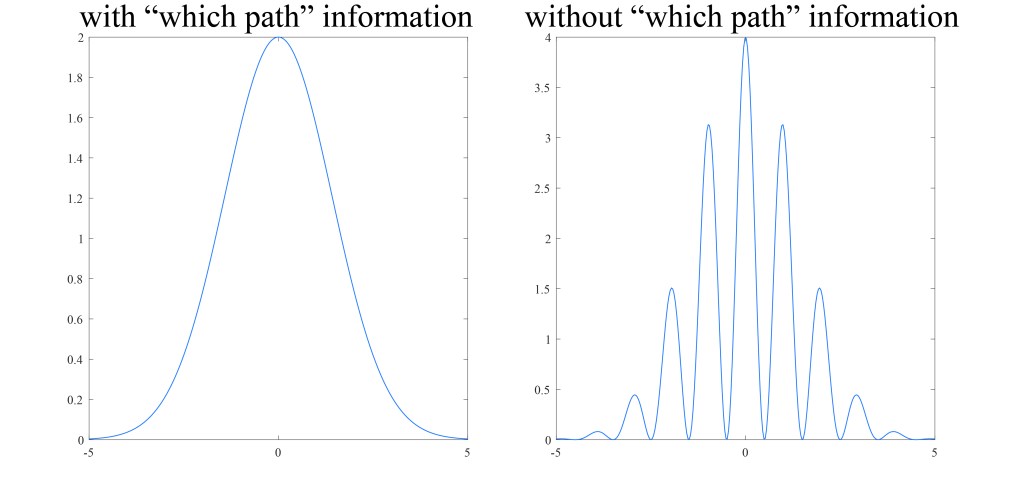

As we have noted, however, orthogonally polarized light waves do not interfere, so the light coming from the two pinholes does not create an interference pattern. By “tagging” which hole the light came through, we have destroyed interference. A rough exaggerated plot of what the intensity would look like on the observation screen with “which path” information and without it is shown below.

Now how can we “erase” the which path information and get back the interference pattern? Let us suppose that we put another large polarizer, oriented at 45 degrees, in the path of the light before it reaches the observation screen. Again, in an oversimplified way, we have:

The horizontal and vertical polarization states have both been “forced” into a 45 degree diagonal state. The original orientation, which told us which hole the light passed through, has been “erased.” Because waves with the same polarization state will create interference, our interference pattern will appear again on the screen — albeit at a lower overall intensity because our second polarization filter has blocked half of the light from passing through.

This example shows the basic concept and principles of a quantum eraser. However, I call this a “trivial” quantum eraser because there is nothing overly quantum about it! The explanation I’ve given above makes perfect sense in the classical “light is a wave” description of light, and I have not needed to invoke the quantum nature of light at all. Arguably, this is still the same phenomenon, as the same arguments apply in the photon picture, but it would be nice to have an illustration of a quantum eraser that explicitly takes advantage of the quantum nature of light. Furthermore, this example doesn’t give us an opportunity to demonstrate the “delayed choice” aspect of the quantum eraser, which is arguably the most interesting part, so we must now look at a more sophisticated experimental arrangement.

(Incidentally, the question of “is it quantum or not?” is a recurring argument in the quantum optics community, as many problems that appear at first glance to be solely quantum turn out to have classical counterparts. One example of this is so-called “classical entanglement,” in which classical waves can be put into states that mirror, to a limited extent, the properties of quantum entanglement. Another example is what is known as ghost imaging, which was first pitched as a purely quantum effect but can be done purely classical as well.)

There is one aspect of the trivial eraser that is of huge relevance to a more explicitly quantum case, however. In our above eraser example, we had the second polarizer oriented at +45 degrees to erase the “which path” information. What happens if we orient it at -45 degrees instead? We still get an interference pattern, but it is shifted relative to the first!

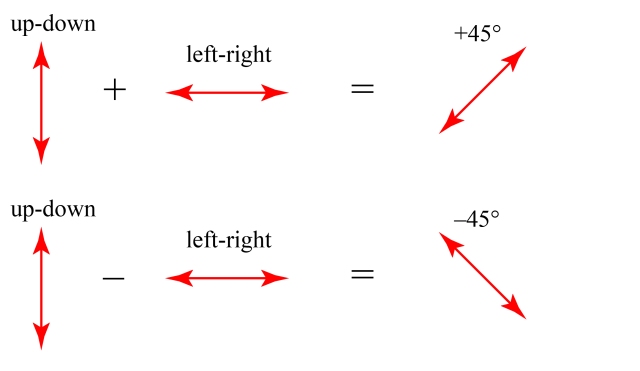

Why does this happen? Let’s look at our earlier image of a polarization decomposition again:

Note the minus sign in the bottom image. When we have our polarizer oriented at +45, both left-right and up-down polarization contribute a +45 polarization state to the output. When we have our polarizer oriented at -45, both left-right and up-down polarization contribute a -45 polarization state to the output, but the up-down contributes it with a minus sign, i.e. what we would call a shift in phase. This shift in phase causes a shift in the interference pattern.

Now the real kicker: what happens if we add the +45 and -45 interference patterns together? Just by looking at the earlier picture you can guess: you get the smooth interference-free intensity pattern you would expect if you still had “which path” information! This phenomenon will reappear in the explicit quantum eraser, which we now turn to.

One note here: it is necessary in the quantum case to delve into a bit more symbolic math, in particular some algebra. If you get lost in the details, take comfort that the description of the trivial eraser covers at least the spirit of what quantum erasers are, even if it fails to capture the most quantum-y aspects of the phenomenon. Also, feel free to skip the mathematics and pick up where it ends, where I try to give a less technical explanation of what is happening.

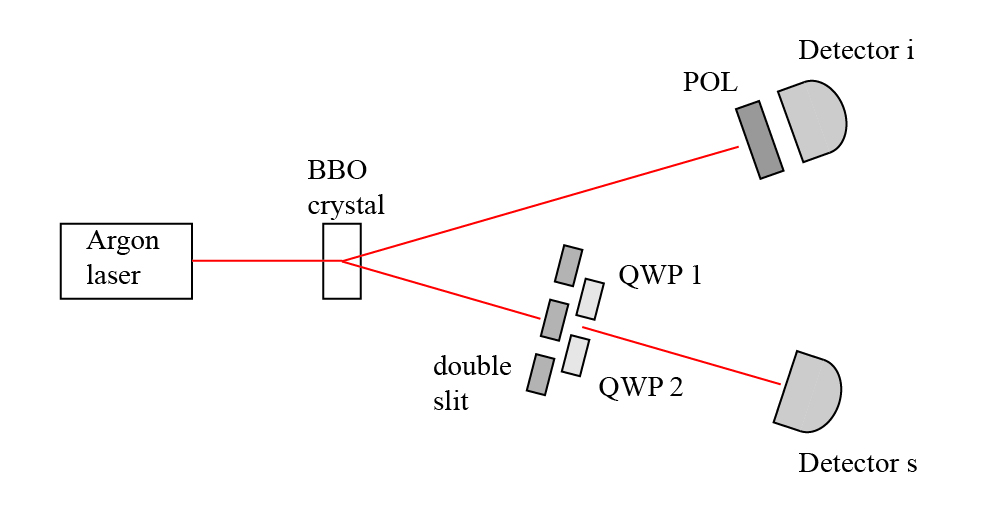

Our explicit quantum eraser discussion follows the experimental setup of Walborn et al.3, which was the first to perform quantum erasure with a Young-type interferometer. Let’s start by introducing a (simplified) version of the experimental setup.

Let’s start on the left and walk through this setup. The source is an argon laser, which pumps a BBO (beta-barium borate) crystal. A significant percentage of photons experience spontaneous parametric down conversion, which means that they split into two photons, each with half the energy of the original, and with perpendicular polarizations. These photons are entangled, but we’ll come back to that in a moment. The lower photon, which we call the signal photon, then passes through a double slit (i.e. two pinhole) screen. Previously, we used polarizers to make the output polarizations perpendicular to each other. Polarizers, however, in general block 50% of photons that are incident upon them if the polarization is random. In this experiment, quarter wave plates (QWP) are used instead. These plates are oriented to convert the potential outputs from the two slits into orthogonal circular polarization states. The net result is the same as using polarizers — any photon that comes out of the double slit has its path tagged by its output polarization.

In the other upper path after the crystal, we have the second photon, called the idler photon. This photon passes through a polarizer (POL) that can have its orientation changed. This will be the device that allows us to keep or erase the “which path” information of the signal photon.

Now we have to talk a bit about entanglement, which is often referred to as the property that distinguishes quantum systems from classical systems. I’ve written a whole series of blog posts trying to explain what entanglement is — for those interested, part 1 can be read here.

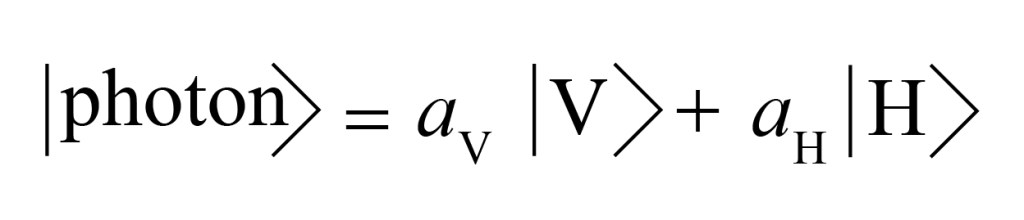

In order to describe entangled systems, we have to introduce a little bit of math notation. We describe the quantum state of an object by the combination |〉, where we put inside this combination the state we are referring to. For example, let us suppose we have a photon whose polarization is some mixture between the perpendicular horizontal (H) and vertical (V) states. We can write the quantum state of the photon in the form:

Here aV and aH represent the wave amplitudes. If we perform a measurement to determine whether the photon is horizontally or vertically polarized, quantum physics says that the probability of getting V for example is

.

It is important to know that the actual state of the photon — is it H or V? — is undetermined until we make our measurement of it. Then the quantum state of the photon “collapses” to that definite value. This is what is known as wavefunction collapse in quantum physics, and it is part of the standard Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics. There are other interpretations, but all of them at this point match perfectly with experiment, so we stick with Copenhagen.

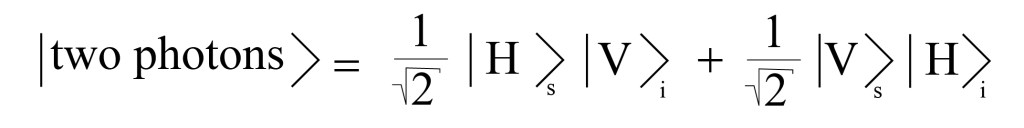

What happens when a photon experiences spontaneous parametric down conversion? Now there are two photons, and a BBO crystal produces photons that are perpendicular to each other. However, nothing forces a particular photon to be horizontal or vertical, so the wavefunction must be a combination of both possibilities. We don’t know the exact state of either photon until we measure one, only that there is a definite relation between them. The combined wavefunction for the two photons becomes

This state indicates that there is a 50% chance that the signal photon is horizontal and, if it is, the idler photon is definitely vertical, and vice-versa. The state is called “entangled” because the fates of the two photons are interconnected and not independent — knowing the state of one tells you exactly what the state of the other is.

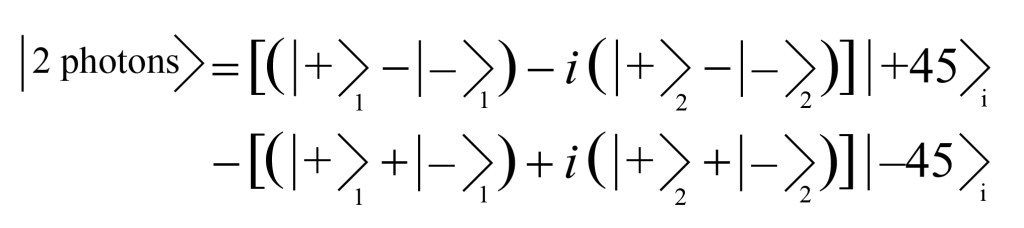

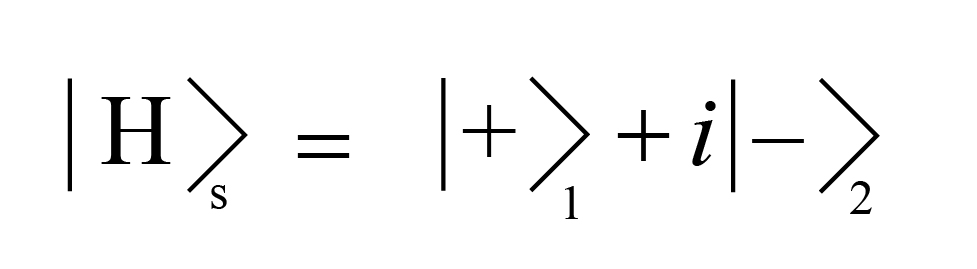

Here’s where things start to get messy. Let us suppose that our signal photon is H polarized. Then, going through the double slit and the quarter-wave plates, it will have an output state like

Here, “+” and “-” represent counterclockwise and clockwise circular polarization, respectively, and “1” and “2” represent the slit the photon passed through. The “i” is the imaginary number, i.e. square root of -1. This wavefunction says, in equation form, “a horizontally polarized signal photon will have a + polarization contribution coming from hole 1 and a – contribution coming from hole 2.”

(Incidentally, I’ve given up on writing the ‘square root of 2’ terms in these expressions. Everything is basically 50-50 in terms of weights from now on anyway.)

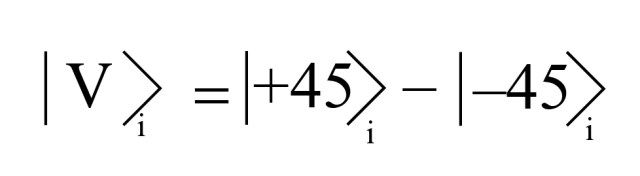

What if the signal photon is V polarized? Then we essentially get the reverse:

Now this wavefunction says, in equation form, “a vertically polarized signal photon will have a – polarization contribution coming from hole 1 and a + contribution coming from hole 2.”

If we then imagine what the combined wavefunction is, including both the signal and idler, after the signal has passed the double slit, we have the messy expression:

With a little reflection, we can see that this wavefunction tells us that we won’t see any interference effects in the double slit experiment. Regardless of whether the idler photon is H or V polarized, the signal photon states coming out of the two slits are orthogonal (fancier word for “perpendicular”) and won’t interfere with each other.

It is worth noting here, however, that we can’t get “which path” information from measuring the signal photon polarization alone, because the polarization of the signal photon depends on what we measure for the idler photon. We can only determine which path the photon took by correlating the polarization measurements of the signal and the idler photons.

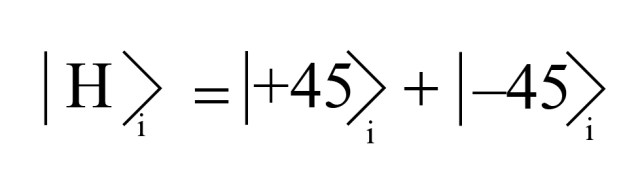

If we measure the idler photon using a polarizer oriented to measure H and V, we therefore can get “which path” information and we won’t see interference fringes of the signal photon, regardless of whether we even bother to measure the signal photon at all! But now let’s imagine that we rotate the polarizer 45 degrees, so now we are measuring whether the idler photon is in the +45 or -45 degree state. Let me share this polarization decomposition image one more time:

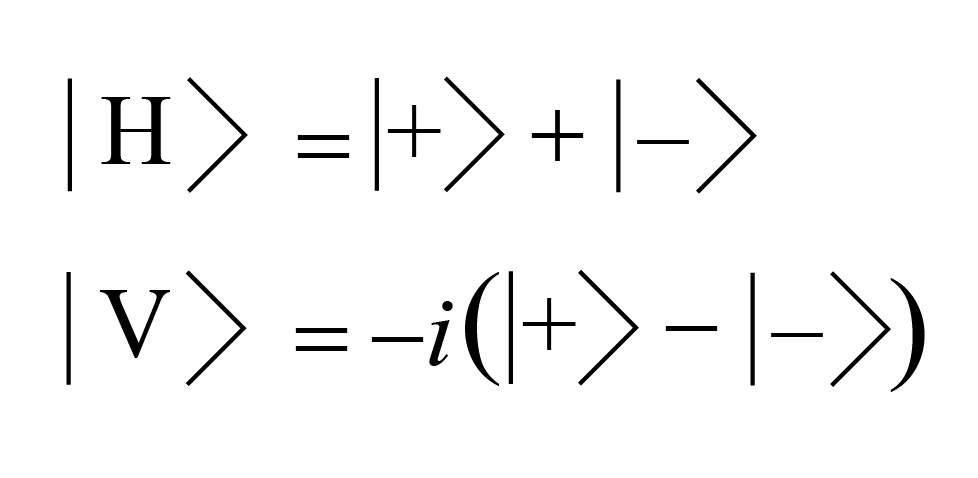

This tells us that if we measure an H or V photon with a +45/-45 analyzer, we have a 50% chance of getting either case! In wavefunction form, we can write the idler photon H wavefunction in the form:

We can also write the idler photon V wavefunction in the form:

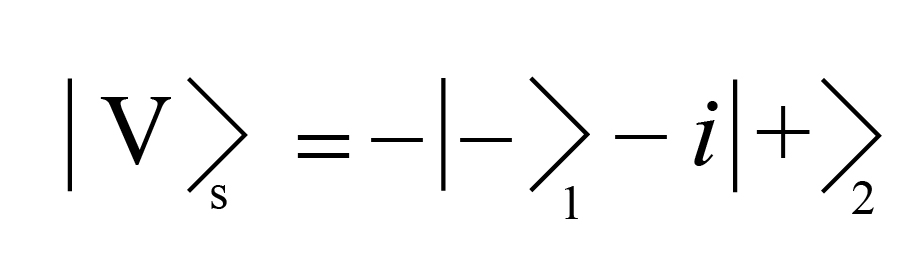

If we substitute from these two expressions into our two photon wavefunction, with a little rearranging we can write

This probably seems like a lot, and it is! However, this expression can be simplified a bit, because the sums of circular polarization states can be written simply as linear polarization states:

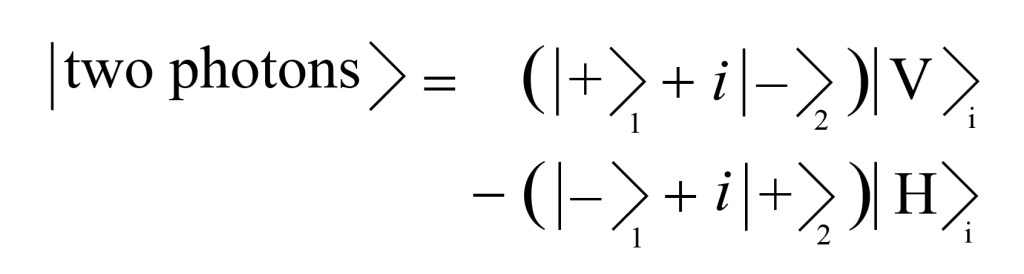

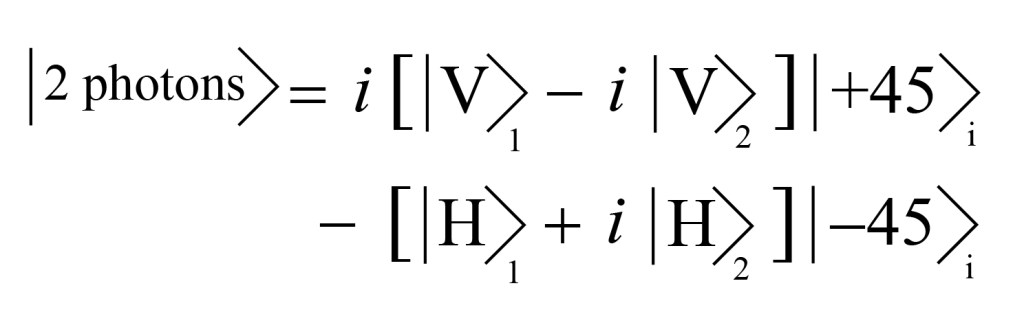

Finally — finally! — we may write the two photon wavefunction in terms of a +45/-45 measurement of the idler photon in the form

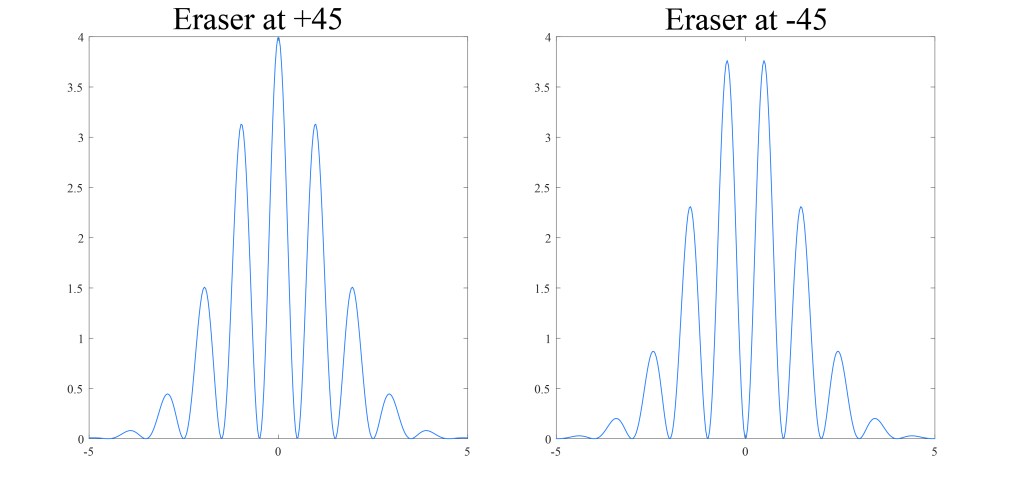

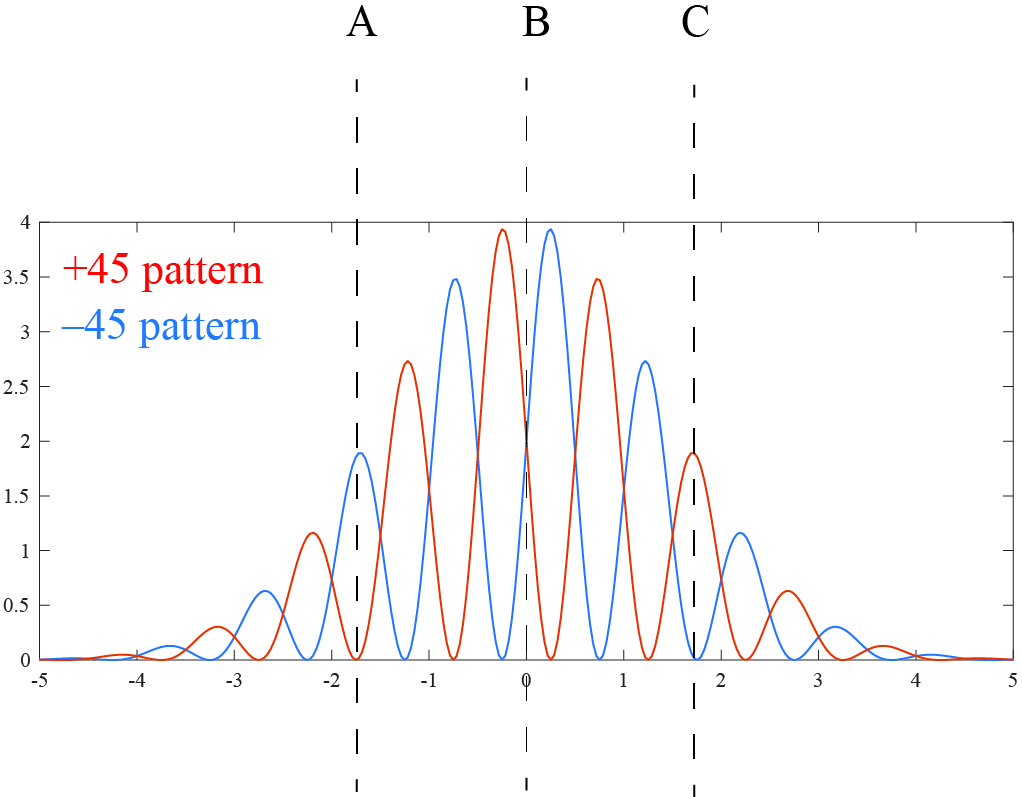

Now let us suppose that the idler photon is measured at +45 degrees. Then the signal photon will pass through both holes with vertical polarization, and will produce an interference pattern. If we measure the idler photon at -45 degrees, then the signal photon will pass through both holes with horizontal polarization, and will produce an interference pattern. Because of the sign difference between the two “i” terms in the equation, the interference patterns for the +45 case and the -45 case will be completely out of phase, i.e. shifted, as we saw in the trivial quantum eraser.

So what can we say is happening here, and how does the eraser work? If we measure the polarization of the idler photon in the H and V orientation, we know for a fact that the signal photon is either V or H polarized going into the slits, respectively, which means they will be perpendicular coming out of the slits and not produce interference. If we measure the polarization of the idler photon in the +45 and -45 orientation, then the state of the signal photon is not well-defined — it can be H(V) entering one slit and V(H) entering the other slit, which means that the filtered outputs of the slits can have the same polarization and cause interference! It would seem, superficially, that we can “erase” the “which path” information by an appropriate orientation of the idler polarizer.

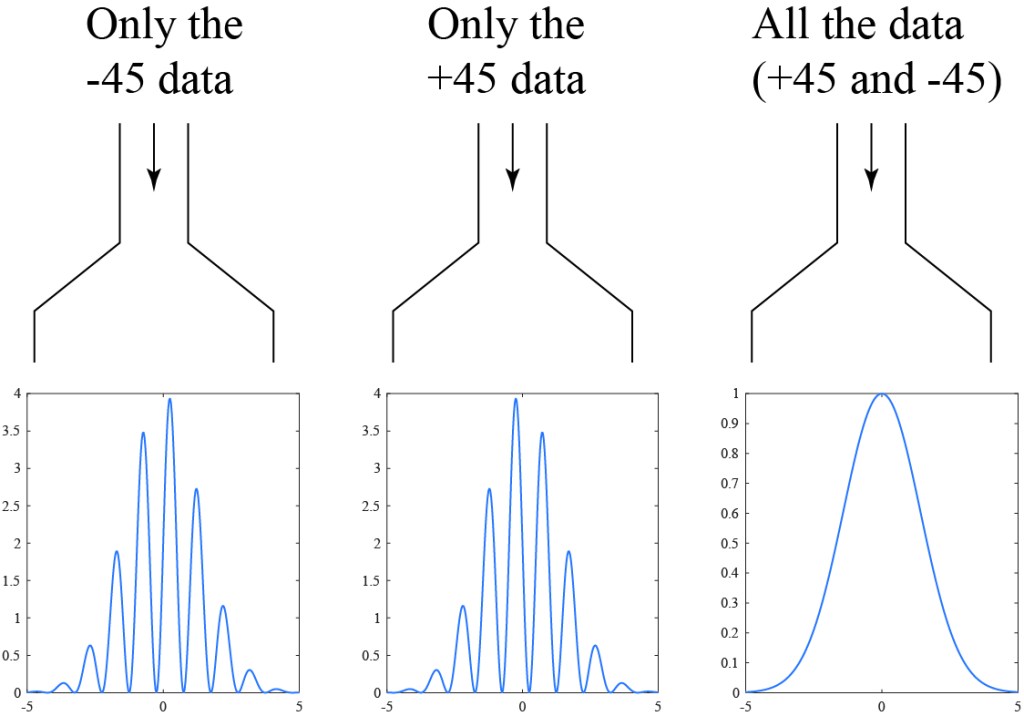

There is a big caveat to this: we have noted that there are two shifted interference patterns, one if the idler photon is measured at +45 and another if the idler photon is measured at -45. In order to see the interference patterns, then, we have to correlate the signal photon positions with the measured state of the idler photon. In other words, we take the data corresponding to a +45 idler and stick it in one bin and that corresponding to a -45 idler and stick it in another bin. The data in those individual bins will show interference patterns. If we just put all the data in one big bin, without caring about what the idler photon is doing? The two interference patterns add up and the result is no interference.

With a little reflection, we can see that the correlation requirement makes sense, and in fact is the only way things could possible work. First of all, it wouldn’t make any logical sense that by simply changing the orientation of the idler polarizer we could cause an interference pattern to appear effectively instantaneously for the signal photons. Second, it would violate our understanding of Einstein’s relativity, i.e. that no information can travel faster than the vacuum speed of light. If the interference pattern could be changed instantaneously, regardless of the distance between the signal and idler measurements, we could in principle come up with some sort of scheme to transmit information as quickly as we would like. In reality, anyone measuring the signal photons without any knowledge of the measured state of the idler photons will see no interference pattern at all — the only way the interference pattern can be seen is by bringing together the correlated data between signal and idler photons, and that “bringing together” can happen at the vacuum speed of light at its fastest.

This has been a quite long post, but there’s one more topic to cover: the concept of the “delayed choice eraser.” The idea here is that we can stretch either the signal or the idler path of our experiment in order to make the signal or the idler measured long before the other.

Let’s imagine that we first stretch the signal path to be really long, so that we have to decide whether or not to erase the “which path” information before we measure where the signal photon lands. Here, we don’t really see a problem — if we choose to make the measurement, we expect that a +45 measurement will make the signal photon align (i.e. the wavefunction collapse) to the +45 interference pattern, and a -45 measurement will make the signal photon align to the -45 interference pattern.

Where things get weird is if we flip the script — let us make the idler path be much longer than the signal path. Now we can measure the position of the signal photon before we even consider what orientation to align the idler polarizer — we make a “delayed choice” on whether to preserve or erase the “which path” information. This is where people initially got really troubled. There are some positions where photons never go in the +45 interference pattern, and likewise some positions where photons never go in the -45 interference pattern. How, then, does the signal photon know which pattern to conform to so that it doesn’t accidentally end up somewhere it shouldn’t be?

This is how people started talking about the signal photon going “back in time” to correct its path through the double slits to conform with the interference pattern. This is completely wrong, and is built on the assumption that the idler photon dictates the behavior of the signal photon in all cases. In the “advanced choice” eraser, it is in fact the collapse of the idler wavefunction that dictates the behavior of the signal photon, but in the “delayed choice” eraser, it is the collapse of the signal photon that dictates the behavior of the idler.

Remember that, before we measure the idler photon state, we expect that the position of the signal photon to conform to the “no interference” pattern, and that this pattern is a combination of the +45 interference pattern and the -45 interference pattern. Now let’s look at those two interference patterns on top of each other.

Suppose we measure the signal photon at position A. The amplitude of the +45 interference pattern is zero there, so there is no chance to measure the idler photon at +45 — it will be found to be at -45. At position C, the amplitude of the -45 interference pattern is zero, so the idler photon will definitely be measured at +45. At position B, the amplitudes of +45 and -45 are the same, so the idler photon will have a 50-50 chance to be measured at +45 or -45. At other positions, the likelihood of the idler being measured at +45 or -45 will depend on the relative amplitudes of the interference patterns.

The “time travel” confusion seems to have arisen from the mistaken belief that our measurement of the idler photon truly controls the behavior of the signal photon. This is not the case — our measurement of the idler photon in the +45/-45 orientation will always be unpredictable, and the measurements of “idler-before-signal” and “signal-before-idler” are entirely consistent with each other and with our understanding of the flow of time.

One final point: it is worth noting that this is all consistent with Einstein’s special relativity. In special relativity, there is a phenomenon known as “relativity of simultaneity,” which means that different observers moving at different speeds and in different directions can disagree on when two distant events happen. One observer might say event A happens before event B, while the other observer might say event B happens before event A. Our discussion of the quantum eraser indicates that both interpretations are equivalent and are indistinguishable from each other, which is what we expect from special relativity.

Whew! This was a long post! I have done my best to explain the concept of a quantum eraser and I hope you have followed most of what I was trying to explain. I wrote this post just as much to clarify my understanding of the topic as to explain it to others, so I expect it is a bit rough around the edges.

So what has the quantum eraser taught us about quantum physics and quantum measurement? It has largely clarified how quantum measurement works and how it doesn’t violate any of our existing understanding of quantum physics or any other physics. The original proposal for the delayed choice quantum eraser could be said to ask the question, “hey, does this make sense?” and the research that followed said, “yes, in a very subtle and unusual way.”

It feels like it tells us something more profound about how the quantum world works, but I have no idea what! To me, it does seem like it leans towards an interpretation of quantum physics called relational quantum mechanics that I discussed briefly in this old post, in which the quantum-ness of a photon is related to the information we have about the photon, but the broader implications are something I will need to ponder some more…

************************************************

- M.O. Scully and K. Drühl, “Quantum eraser: A proposed photon correlation experiment concerning observation and “delayed choice” in quantum mechanics,” Phys. Rev. A 25 (1982), 2208.

- HILLMER, RACHEL, and PAUL KWIAT. “A Do-It-Yourself QUANTUM ERASER.” Scientific American 296, no. 5 (2007): 90–95.

- S. P. Walborn, M. O. T. Cunha, S. Padua, and C. H. Monken, “Double-slit quantum eraser,” Phys. Rev. A 65, 033818 (2002).

I thought you might be interested in this. My book Ibn al-Haytham First Scientist, which you kindly reviewed in your blog, has been translated into Arabic and published by the Saudi Philosophical Association, which is part of the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture (Ithra).

Brad

The copy below reads:

Now available, the book “Ibn al-Haytham: The First Experimental Scientist” by Bradley Steffens, translated by Abdul Rahman Al-Marzouki. The book presents an important biography of the experimental scientist Ibn al-Haytham and his most notable contributions to experimental scientific methodologies through the study of optics and the transmission of light.

Price: 25 Riyal

Supported by #Ithra and #Cultural_Fund as part of the #Ithra_Arabic_Content initiative

@ithra

@cdf_sa

@ibnzadan

For contact via WhatsApp: 0552229306

Or the website

[cid:cf58ea29-9def-4215-8cde-d0c88af87983]

My comment was rejected because it said that comments are closed.

Could that be Akismet wrongly rejecting it?

I’m trying this again.

Classical physics says that radiation is created by accelerating charges. It travels through space at lightspeed, and occasionally it accelerates charges whose behavior can be detected — that’s how we detect light.

Radiation typically travels as waves because accelerating charges are typically periodic.

Is there a possibility that this is mostly correct? Three things happen — light is created. Light travels through space. Light is absorbed by atoms and detected.

Atoms are quantized. If light has quantum properties while it travels through space, then light is definitely quantized. If it has quantum properties while it interacts with atoms, then maybe.

Photo-electric effect — maybe atoms absorb a quantum of light energy from a wave, and then emit an electron.

Is there a quantum effect that has to come from quantized light and not atoms?