Most of us have heard a statement similar to the one that follows: “The speed of light is constant.” That particular phrasing of the statement comes from none other than the American Museum of Natural History’s Einstein exhibit, so I think it is fair to say that most people have heard it phrased in this way at one time or another.

Most physicists would add one very important caveat to this statement to reduce confusion: “The speed of light is constant in vacuum.” It is in this sense that it forms part of the foundation of Einstein’s special theory of relativity: any observer measuring the speed of a light wave traveling in vacuum will measure exactly the same result, about 186,000 miles per second or 300,000,000 meters per second, usually labeled c in physics. Different observers moving relative to one another will agree that a given light wave is moving at c, even if one is moving towards the light source and one is moving away from the light source! This is in contradiction to our day-to-day intuition: if I am driving towards a car that is approaching me, it will move towards me faster than if I am driving away from it.

From Einstein’s special theory of relativity, and the observation that “the speed of light is constant in vacuum,” comes all sorts of non-intuitive phenomena, like length contraction and time dilation and the idea that, as far as we know, nothing can move faster than c! Apparently the “speed of light” is the speed limit of the universe.

The statement “the speed of light is constant” is therefore arguably more accurate than not, but leaves out a lot of subtlety in discussions of the speed of light! I recently started thinking about the speed of light from an optical science perspective due to a question from a Twitter friend, and I thought I would muse a bit on all the ways that the speed of light is harder to define than you might think, even without talking about objects in relative motion.

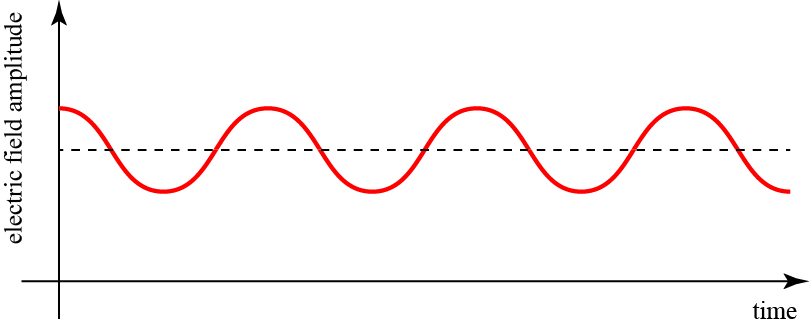

Let’s start with a discussion of light traveling through matter; in fact, some of the most surprising results will arise when we talk about light traveling in a vacuum! We consider, at first, a single frequency (i.e. “single color”), or monochromatic, wave. If we were to plot the “ups and downs” of a single frequency wave in time, it would look something like this:

In a light wave, the thing that is “waving” is its electric field (and magnetic field along with it). Different colors of light correspond to different frequencies of light (or combinations of frequencies). Using some numbers from Britannica, red light is 462 trillion cycles per second, and blue light is 666 trillion cycles per second. With light waves oscillating that fast, we do not detect the oscillations directly, of course.

In space, we have a very similar picture of a monochromatic wave: the electric field “waves” up and down along the direction it is traveling:

How do we measure the speed of a monochromatic light wave? We simply look at how fast the peaks of the wave are moving in space; this is called the “phase velocity” of light. It is one of several velocities of light we’ll be talking about before we’re done!

What happens to the speed, i.e. the phase velocity, of light when it enters a transparent medium, like glass or water? Typically, we expect it to slow down, by an amount we refer to as the refractive index n. That is, if we refer to v as the phase velocity of our wave in the medium, then we have v = c/n. For the blue light frequency given above, the refractive index is n = 1.337. This means that the speed of light in water at this frequency is about 3/4ths what it is in vacuum (1/n is approximately 3/4).

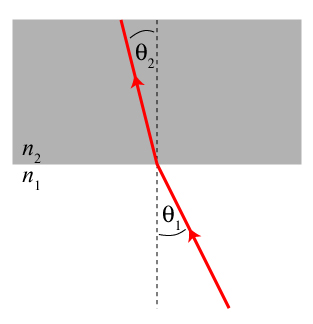

This change in speed is also what causes the phenomenon of refraction, which is the change in direction of a light wave as it passes from one medium to another; this, of course, is why we call n the “index of refraction.”

Why is the speed of light slower in matter? Here, we can make a rough analogy similar to the one used to describe the Higgs boson: a cocktail party. A popular person moving through the crowd at a cocktail party typically ends up moving slower, because they end up stopping and conversing with different party guests along the way. Similarly, a light particle (a photon) moves slower when it moves through matter because it ends up interacting with all the atoms in its path.

But now we get to complications! You may have noticed that above I mentioned the index of refraction for blue light, specifically. Is the index of refraction different for different colors of light? Yes, it is: the index of refraction of water for red light is n = 1.331, not much different than blue light but definitely different. This phenomenon, in which the refractive index depends on the frequency of light, is known as dispersion. One very familiar illustration of dispersion is the breakup of a beam of white light into its constituent colors in a glass prism, such as depicted on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album:

This presents a problem: how do we define the speed of light in a dispersive medium? If we are working with a beam of light that is mostly red, i.e. mostly monochromatic, then the phase velocity is a decent approximation of the speed of light.

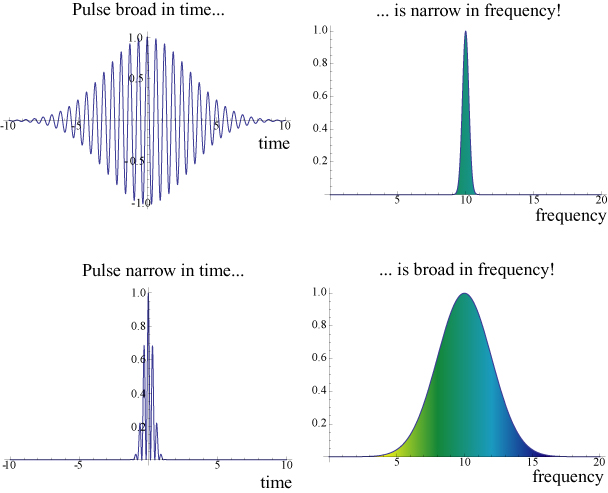

But often we send short pulses of light through a medium, sometimes ultrashort pulses. Femtosecond laser pulses are not uncommon in optics: that is a pulse of light with a duration of a millionth of a billionth of a second. The shortest light pulses ever achieved in the laboratory are even shorter, with a duration of an attosecond: one billionth of a billionth of a second.

One fundamental aspect of optics is that the shorter a pulse is, the broader its frequency spectrum (the range of colors it contains) is. A short optical pulse is therefore comprised of a range of colors, and each of those colors travels with a different phase velocity. How, then, do we define the speed of the light pulse? The inverse relationship between the pulse width in time and in frequency is illustrated below. If we have a narrow pulse, with a broad frequency spectrum, there is no obvious way to relate the phase velocities of all the colors present to the overall speed of the pulse.

There is another, even bigger, problem with the phase velocity. Atoms have certain special frequencies at which they absorb and emit light or other energy, often referred to as resonance frequencies. If we look at the value of the refractive index near one of these resonance frequencies, we find that it can be less than one. This means that the phase velocity of a monochromatic wave can be faster than the vacuum speed of light near a resonance frequency.

This leads us to one of two conclusions: either Einstein’s special theory of relativity is wrong, or the phase velocity is a bad description of the speed of a pulse of light. Physics has decided on the latter choice: because a pulse of light contains many frequencies, each of which has its own phase velocity, in general it does not make sense to talk about the “phase velocity of a pulse.”

To circumvent this, physicists devised another measure of the speed of a pulse of light, known as the group velocity. In essence, the group velocity is a measure of how fast the “center of energy” (analogous to the center of mass) of the pulse travels. If you send a light pulse with a single peak into the medium, and it comes out with a single peak, the group velocity is a measure of how fast the peak traveled through the medium.

Here’s where things get really weird! First of all, we note that, in certain special materials, light can be made to travel really, really slowly. In 1999, researchers used a Bose-Einstein condensate1 to slow a pulse of light to 17 meters per second, about 38 miles per hour! This is a pulse of light that you could easily beat in a race with a car.

Furthermore, in 2001 the same researchers showed2 that they could effectively stop a light pulse dead in its tracks and hold it there for one millisecond! They used a phenomenon called electromagnetically induced transparency, in which one light beam (the pump) illuminating a medium makes it transparent for a second light beam (the probe). The researchers sent the probe pulse into a medium and then switched off the pump momentarily while the probe was inside. The probe was effectively stuck in an interaction with the atoms of the medium; to use our cocktail party analogy from above, the probe pulse was dragged into a very interesting conversation! By turning the pump beam back on, the probe pulse was sent back on its way.

But things can get even stranger for the group velocity: if we send a pulse through a medium with a frequency range near an atomic resonance, the group velocity of light is also often greater than the vacuum speed of light! How can this be possible without violating Einstein’s universal speed limit?

Before answering that, let me note that there are other definitions of the speed of light in a medium. One of these is the front velocity, which is the speed at which the leading edge of a pulse moves in a medium. This front edge of the pulse is hard to mathematically define in general, but experimentally it has never been found to exceed c. Often described in the same sense is what is called the signal velocity, which is the speed at which a signal carrying information can be transmitted in a medium. The signal velocity and the front velocity are largely equivalent, and neither of them can exceed c as far as we know.

So how can the group velocity of a pulse move faster than the pulse itself? We first note that, at a resonance frequency of matter, light is strongly absorbed. If we fire a pulse with a frequency range close to a resonance frequency, we expect that the pulse will be strongly absorbed as it travels.

Now let’s turn to analogy! Let’s imagine a bus filled with passengers. At each stop, passengers get off at the back of the bus, but nobody else moves from their position. What happens to the center of mass of the passengers? It moves forward in the bus.

We have the counterintuitive but understandable situation that the center of mass of the passengers on the bus is moving faster than the bus itself! The bus speed is analogous to the front velocity of a light pulse, and the center of mass speed is analogous to the group velocity. In a light pulse near a resonance, light gets absorbed preferentially from the back of the pulse, making the peak of the pulse appear to move forward. The pulse itself gets smaller and smaller, however, as it travels, and no matter how fast the center of mass moves, it can never get ahead of the bus.

A similar thing can happen in a gain medium, in which atoms already have energy stored at a resonance frequency. Instead of light being absorbed as it passes through the medium, it causes the atoms to emit their stored energy as more light, in a process called stimulated emission. (This is the basic physics that makes a laser possible.)

To use the bus analogy again, now we imagine that at each stop new people get on the front of the bus, and everyone else stays where they are. Again, the center of mass of the passengers moves towards the front of the bus, making the center of mass move faster than the bus itself! In a light pulse, photons get released from atoms at the front of the pulse, adding to the intensity of the pulse at the front and making the peak of the pulse move forward. The pulse adds energy as it travels, picking it up from the atoms. But again, nobody ever gets ahead of the bus itself.

So group velocity can be greater than c, but still the signal velocity remains c, so relativity is not violated. We cannot transmit any useful information with the group velocity, only the signal velocity, and this becomes a caveat to saying “nothing can travel faster than c.” Instead, we have “nothing useful can travel faster than c.”

These gain and loss scenarios were well-known to physicists for years. However, this didn’t prepare researchers for research that was published3 in 2000, showing that it is possible for a pulse to travel with a superluminal group velocity and come out of the medium with the same amount of energy it had going in!

This paper caused physicists to lose their minds when it came out, and it really shouldn’t have. The researchers used a medium that had two gain resonances, but propagated their pulse at a frequency between these resonances. The result is a pulse that had energy added to its front and removed from its back, leaving it with the same amount of energy but with the peak shifted forward. To use our bus analogy again, passengers get off the back of the bus and get on the front of the bus so that the number of passengers is the same but the center of mass has shifted forward. Again, no individual (no photon) actually moves faster than the front of the bus (front of the pulse).

In many situations, there is no single number that can adequately describe the speed of light. If a short pulse of light travels a long distance in a dispersive medium, it might break up into multiple parts, each of which travels at its own speed! For decades, people have known that a pulse may generate precursors in such a case, two parts of the pulse that travel faster than the main body of the pulse, which travels at the group velocity.

The so-called Sommerfeld precursor is theoretically predicted to travel at the vacuum speed of light, even though it is in a medium; I’ve blogged before how researchers have used precursors to study whether any part of a light pulse can travel faster than c in matter. (So far, the answer is “no.”)

Precursors show that describing the speed of light in matter can be a tricky business. Light is “squishy,” and unlike a rigid body like a car there is no unique part of a light pulse that we can track to define light’s speed. In the precursor case, there are three distinct parts of the propagating pulse, each of which travels at its own speed!

So when we talk about the speed of light, it turns out that it can be a surprisingly tricky thing to define when light is propagating through matter! What becomes especially surprising is that even light propagating in a vacuum can give us some unexpected surprises, as I will discuss in part 2 of this post!

**********************************

- Hau, L., Harris, S., Dutton, Z. et al. Light speed reduction to 17 metres per second in an ultracold atomic gas. Nature 397, 594–598 (1999).

- Liu, C., Dutton, Z., Behroozi, C. et al. Observation of coherent optical information storage in an atomic medium using halted light pulses. Nature 409, 490–493 (2001).

- Wang, L., Kuzmich, A. & Dogariu, A. Gain-assisted superluminal light propagation. Nature 406, 277–279 (2000).

Light is “squishy” – love it! Hope you won’t mind if I quote this to students. Wonderful story-telling and a delight to read. Looking forward to reading part 2; a treat for tomorrow’s toast 🙂

You are most welcome!