So a few weeks ago I described a 1960 experimental test of time dilation in Einstein’s special theory of relativity that applies the Mössbauer effect to measure precise changes in the frequency of gamma rays. I only briefly described the Mössbauer effect in that post, and it’s a simple enough and interesting enough effect to elaborate upon in a separate post, so here we are!

In short, the Mössbauer effect is the absorption of a gamma ray by an atomic nucleus in a crystal such that the momentum of the gamma ray is absorbed by the entire crystal array, rather than the single nucleus that absorbed the gamma ray. Why this is significant is a longer story, which we now discuss.

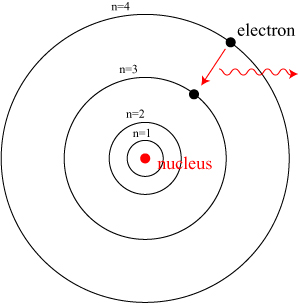

Let’s begin with a discussion of spectroscopy and how photons of different energies can be use to study different parts of the structure of atoms. I’ve talked many times about the Bohr model of the atom, usually pictured something like the image below.

In the days before we discovered quantum physics and the structure of the atom, researchers couldn’t understand why atoms seemed to absorb and emit light only at very specific discrete frequencies. Niels Bohr proposed a model of the atom in which electrons can only orbit the nucleus at special orbits, labeled by a number n, and would emit or absorb a single photon in jumping from one state to another.

This picture of electrons “orbiting” the nucleus would quickly be supplanted by a picture of electrons as extended waves enveloping the nucleus, but the basic principle introduced by Bohr — of discrete states for electrons and a discrete emission spectrum — holds up. People still use the term “orbits” to describe the states of the electron, despite its inaccuracy, because it gives a decent enough image.

Continue reading