I’m currently writing a textbook on Electromagnetic Waves for my graduate optics students. I was reading up on zero refractive index materials for a chapter section and thought it would be fun to write a popularized account of their fascinating and counterintuitive properties!

The past two decades have been a fascinating time to be an optics researcher. During that period, old rules about what light can and cannot do have been found in many cases to be more like guidelines, and ignoring those guidelines have led to some really astonishing new optical phenomena and devices.

One area where the rules have changed dramatically is in our understanding of the refractive index of light. The refractive index of a material, usually expressed in mathematical equations by the symbol n, represents the amount by which the speed of light is reduced in the medium from its vacuum value. If we label the speed of light in vacuum as c, then the speed of light in the medium is given by c/n. As an example, the refractive index of water in the visible light spectrum is roughly 1.33, which means that the speed of light in water is c/1.33, or 3/4ths the vacuum speed of light.

The most famous and most dramatic demonstration of seeming rule-breaking is the demonstration of materials with a negative index of refraction. When light travels from one medium to another, its direction changes according to the law of refraction, known as Snell’s law.

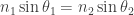

Mathematically, we write Snell’s law as

.

.

where “sin” represents the trigonometric sine function. This formula indicates that when light goes from a rare medium (low refractive index) to a dense medium (high refractive index), the light direction bends towards the perpendicular to the surface.

But what if the second medium has a negative index of refraction? Then Snell’s law would tell us that the light would bend on the opposite side of the perpendicular to the surface.

For centuries, this was assumed to be impossible, because among other things how could light have a negative speed? But in the 1960s, Russian physicist Victor Vesalago argued1 that there is nothing in physics that prohibits a negative refractive index, and further argued that a negative index material could be used to make a flat lens, as illustrated below.

Veselago’s work went largely unnoticed until, in 2000, UK physicist John Pendry noted2 that not only was Veselago’s lens possible, but it would in principle have perfect resolution, violating another long-held belief by optical scientists that imaging systems always have finite resolution.

Pendry’s result requires the fabrication of materials with optical properties that do not exist in nature, now called metamaterials. A metamaterial is a material that gets its optical properties from an artificial subwavelength-size structure. Many scientists initially scoffed at Pendry’s predictions, but materials with a negative refractive index3 were fabricated soon afterward, and rough experimental tests4 of the perfect lens prediction demonstrated that the principle is sound.

The introduction of negative refraction led physicists to ask: what other types of very unusual optical materials are possible, and what might they be used for? One obvious answer to the question was: we can make materials with a refractive index that is zero, or very close to zero! Such materials are known as “epsilon near zero” (ENZ) materials, and let’s take a look at what they can do.

Continue reading →

The author of Skulls in the Stars is a professor of physics, specializing in optical science, at UNC Charlotte. The blog covers topics in physics and optics, the history of science, classic pulp fantasy and horror fiction, and the surprising intersections between these areas.

The author of Skulls in the Stars is a professor of physics, specializing in optical science, at UNC Charlotte. The blog covers topics in physics and optics, the history of science, classic pulp fantasy and horror fiction, and the surprising intersections between these areas.